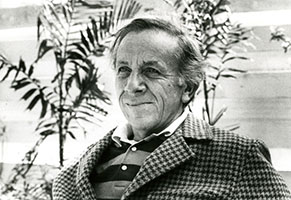

In October of 1994, my sister Bess had recently begun working as a nurse in the Medical Intensive Care Unit at University Hospital in Charlottesville. One afternoon, she called me to ask if I’d ever heard of a writer named Peter Taylor. “He came into the MICU last week,” she said. “He’s one of my patients.”

Though I hadn’t read any of his work yet, I had heard of Peter Taylor. I knew he was considered a master of the short-story form—sometimes called the American Chekhov—and that he had been a professor at the University of Virginia for many years. And I knew that he had studied writing under Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, and Robert Penn Warren, which, to a young Southerner with literary aspirations, seemed a distinction roughly equivalent to learning Latin from Vergil, Horace, and Ovid.

Though I hadn’t read any of his work yet, I had heard of Peter Taylor. I knew he was considered a master of the short-story form—sometimes called the American Chekhov—and that he had been a professor at the University of Virginia for many years. And I knew that he had studied writing under Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, and Robert Penn Warren, which, to a young Southerner with literary aspirations, seemed a distinction roughly equivalent to learning Latin from Vergil, Horace, and Ovid.

“What’s he like?” I asked.

There wasn’t much to say. Taylor was elderly and very ill—he had come into the MICU after the second of a series of strokes—but he was warm and funny and kind, despite his discomfort.

When Bess told him she had a brother in college who was an English major and hoped to become a writer, Taylor told her about his father, a prominent attorney and insurance executive, and how he had disapproved of his son’s decision to pursue writing as a career. When the subject of his career came up, Taylor explained, his father would invariably tell whoever asked that his son was a teacher. For most of his life, Taylor himself had followed suit, introducing himself to strangers simply as a teacher.

I absorbed this anecdote with circumspection. Was it meant to impart some lesson about values or humility, or was it merely an old man’s reminiscence? Did Taylor agree with his father that teaching was a nobler, prouder vocation than writing? Was this recollection an example of Taylor’s famously dry wit? Did it reveal a hint of resentment?

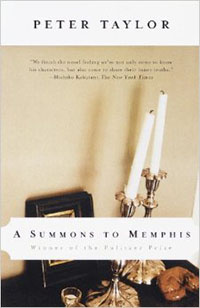

Intrigued, I proceeded directly from that conversation to the nearest bookstore, where I picked up the only volume of Taylor’s available: his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, A Summons to Memphis.

The story my sister told me seemed especially apt to the tone and substance of that slim, elegant novel. At twenty, I was not yet mature enough to sense its irony. One needs a bit of seasoning, I think, to appreciate the subtlety with which Taylor dissects the society of the upper-class urban South, finding within its rituals and cultivated mores an archetypal tale resonant with echoes from Sophocles on through Shakespeare, Turgenev, and Faulkner.

The premise of A Summons to Memphis is deceptively simple, even comical: Phillip Carver, forty-nine-year-old New York editor and Southern expatriate, is called home to Memphis by his sisters, who want his help in preventing their elderly father from marrying a much younger woman. In short order, we learn that the Carver sisters’ motivation is not money, or even protectiveness, but revenge.

Years earlier, after suffering a personal betrayal and a professional fall from grace, George Carver had uprooted his family from Nashville to start over in Memphis. The patriarch restored his wealth and reputation, but his wife withered and died, and his children fell into a state of arrested development, unable to adapt and evolve in a world in which their place was not already secured. So the sisters have determined that their father must not be permitted a second chance at happiness after having denied a first to all of his children. “I believe it is a maxim beyond contradiction,” Phillip Carver opines, “that high ambition and worldly aspirations are all very well and even commendable so long as other persons are not asked to share the risks created and confronted by the protagonist.” Beyond contradiction, indeed.

Years earlier, after suffering a personal betrayal and a professional fall from grace, George Carver had uprooted his family from Nashville to start over in Memphis. The patriarch restored his wealth and reputation, but his wife withered and died, and his children fell into a state of arrested development, unable to adapt and evolve in a world in which their place was not already secured. So the sisters have determined that their father must not be permitted a second chance at happiness after having denied a first to all of his children. “I believe it is a maxim beyond contradiction,” Phillip Carver opines, “that high ambition and worldly aspirations are all very well and even commendable so long as other persons are not asked to share the risks created and confronted by the protagonist.” Beyond contradiction, indeed.

Taylor was, of course, born into the genteel milieu which serves as his subject: one grandfather was a Confederate colonel who served under Nathan Bedford Forrest; the other served as both a Tennessee governor and U.S. senator. His stories and novels are set in the world he describes in A Summons to Memphis: a place of “steeplechase weekends up in Sumner County [and] musical afternoons at the Nashville Centennial Club or serious literary evenings centered on some professor from Vanderbilt (with his reconstructed views on the advancing South) or formal dinner parties with the women going upstairs after dinner.”

Taylor’s take on this culture is understandably ambivalent. It’s his world, after all; to disown it would be to reject his heritage. And there is undoubtedly an allure to the mannered idealism of the old guard in Southern cities like Nashville and Memphis, despite the taint of its origins in slave-holding plantations and the perpetuation of a bigoted caste system “where phrases like ‘well bred’ and ‘well born’ were always ringing in one’s ears and where distinctions between ‘genteel people’ and ‘plain people’ were made and where there was rather constant talk about who was a gentleman and who wasn’t a gentleman.” Taylor’s genius is to render faithfully the romantic appeal of this culture while simultaneously acknowledging the moral rot beneath its polished surfaces.

The autobiographical subtext in A Summons to Memphis is undisguised. In its pages, we see Taylor wrestling with the complex influence of his father’s legacy and the manner in which his own privileged upbringing shaped his worldview. The principal archetype at play in A Summons to Memphis is the son’s struggle against the will and image of the father, but there is also a yearning for the stability that was lost to the Carver children when they were forced to leave Nashville. Taylor understands that this society, like all such structures, began primarily as a means of establishing a place of peace and belonging, and that such peace is easily crushed by unpredictable reversals of fortune, or hubris, or repressed wounds destined to resurface and expose the citadels of comfort we’ve built up around ourselves as fragile and illusory.

Only a few days before he died, Peter Taylor had his wife Eleanor bring a book for him to sign as a gift for my sister—his last story collection, The Oracle at Stoneleigh Court. He was too weak by then to write the inscription; next to his failed scrawling, he had my sister write these words: “To Bess Tarkington, for making my life endurable.” Beneath, he scratched out his name, in unsteady block letters reminiscent of a child’s first efforts. It is not unreasonable to suppose that the book was the last one he ever signed. When I look at the shaky scrawl of his signature, I am reminded of these words from the closing paragraph of A Summons to Memphis: “[W]hen the dusk of some winter day fades into darkness we’ll fail to put on the lights in these rooms of ours, and when the sun shines in next morning there will be simply no trace of us. We shall not be dead, I fantasize… Our serenity will merely have been translated into a serenity in another realm of being.” Should such a wish be too much to hope for?

Ed Tarkington holds a B.A. from Furman University, an M.A. from the University of Virginia, and a Ph.D. from the creative-writing program at Florida State University. His debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.

This essay is part of the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prize board and the Federation of State Humanities Council in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. For their generous support of the Campfires Initiative, we thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes board, and Columbia University.

Tagged: Fiction, Pulitzer100