Nothing More Autobiographical

Lorrie Moore’s See What Can Be Done is a window into a lively mind

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on April 9, 2018.

***

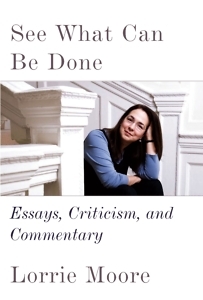

In a review of Richard Ford’s Canada included in her new collection, See What Can Be Done: Essays, Criticism, and Commentary, Lorrie Moore describes Ford as “a writer of jangling personal fascination to many in the literary world.” She might as well have been writing about herself.

Since the publication of her landmark story collection, Self-Help, when she was only twenty-eight, Moore has been the object of an esteem that borders on obsession from readers and especially from fledgling writers. How many thousands of second-person-narrator stories have been passed around writing workshops since the publication of Moore’s “How to Become a Writer”? Only Raymond Carver could be accused of inspiring more derivative work—imitation being, as the saying goes, the sincerest form of flattery.

Moore’s cult-heroine status may be somewhat owed to her literary arrival just before the ubiquity of the Internet. In those years, writers like Ford, Carver, Tobias Wolff, Mary Gaitskill, Ann Beattie, and Amy Hempel replaced the old gods in the hearts of a new generation. All we knew about them came from their work, their hip, faintly mysterious dust-jacket photos, and the occasional profile or interview, easy to miss in those days before social media. Moore—who now teaches in the M.F.A. program at Vanderbilt University in Nashville—rose to literary fame before the open-book accessibility expected from writers entering the publishing world today.

She remains at once the most relatable of writers and the most remote. Her 1998 collection, Birds of America, became that rarest of literary events, a bestselling volume of short stories, and contributed another addition to the M.F.A. workshop reading list: “People Like That Are The Only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Onk,” a riveting, heartrending account of an infant afflicted with a rare cancer and the parents’ odyssey through the world of Pediatric Oncology. Word circulated that Moore had based the story on personal experience, but how much truth was in the rumor?

No writer whose work inspires such ardor escapes this kind of speculation, particularly in our time, when people have become so comfortable exhibiting their own private lives. “Fiction writers are constantly asked, is this autobiographical?” Moore writes. “Book reviewers aren’t asked this; and neither are concert violinists, though, in my opinion, there is nothing more autobiographical than a book review or a violin solo.”

With See What Can Be Done, she delivers something more revealing than a tell-all interview: a window into the workings of her own formidable mind. The pieces, collected over several decades—many of them originally published in The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books—cover a staggering range of topics, from the murder of JonBenét Ramsey to HBO’s The Wire to, of course, the novels and stories of both her influences and her contemporaries.

Moore’s literary criticism is unsurprisingly insightful, but it is also animated with the wit for which she is revered. Moore on Kurt Vonnegut: “that paradoxical guy who goes to church both to pray fervently and to blow loud, snappy gum bubbles at the choir.” On John Cheever: “a man who found himself alone in a way he could never quite accept, in a way that took him completely against his will.” On Alice Munro: “she knows that the arranging of love, improvised or institutional, and the seismic upheavals of its creation and dismantling—the boards rising precariously beneath the feet—is both a kind of pornography of life and the very truth of it.” On Welty: “If her life had fallen into a trap or two, well, the world is full of traps of all sorts and one can find some writer or other in each and every one of them.” In these examinations of Moore’s fellow writers, one senses both intuition and confession.

Moore’s literary criticism is unsurprisingly insightful, but it is also animated with the wit for which she is revered. Moore on Kurt Vonnegut: “that paradoxical guy who goes to church both to pray fervently and to blow loud, snappy gum bubbles at the choir.” On John Cheever: “a man who found himself alone in a way he could never quite accept, in a way that took him completely against his will.” On Alice Munro: “she knows that the arranging of love, improvised or institutional, and the seismic upheavals of its creation and dismantling—the boards rising precariously beneath the feet—is both a kind of pornography of life and the very truth of it.” On Welty: “If her life had fallen into a trap or two, well, the world is full of traps of all sorts and one can find some writer or other in each and every one of them.” In these examinations of Moore’s fellow writers, one senses both intuition and confession.

Equally absorbing, if not more so, are the many essays on other subjects—the Clinton-Lewinsky-Starr debacle, Moore’s first job, the 2011 GOP primary debate, Helen Gurley Brown, assorted films and television shows. The combined effect of these pieces is weirdly reassuring: yes Virginia, even the most brilliant and ambitious writers binge on Friday Night Lights. “I have aimed for the human, but also for the eccentricities and particularities of the real encounter, and I do not always avoid stupidities,” Moore writes. “Sometimes I head for stupidities in order to discuss them, even if they are my own.”

You get the sense that you’re hanging out with that remarkably wise, funny friend who knows just how to articulate what you were thinking in a manner you’d never have landed upon yourself. “Whatever its seductive impingements, in literature biography is never the point,” Moore writes. “In biography’s attempts to know the exact midwifery between life and art, it is always guessing.” The Moore we surmise through See What Can Be Done is as good a guess as we could hope for.

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.