Inundated

Rhodes professor Jeffrey H. Jackson considers the Paris flood of 1910—and its eerie similarity to New Orleans after Katrina

In January of 1910, the river Seine rose twenty-five feet above normal levels, inundating the city of Paris and its environs. Although the flood was unquestionably a national disaster of epic proportions, it is scarcely remembered today. A few high-water marks scattered around the city still commemorate the flood, but the extent of the damage, as well as the heroic efforts of the Parisian citizens both during and after the flood, are seldom recalled.

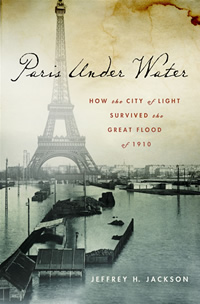

Paris Under Water: How the City of Light Survived the Great Flood of 1910, Jeffrey H. Jackson’s thoughtful and thorough exploration of the flood and its effect on French history, aims to set the record straight. Jackson, a professor of history at Rhodes College, spent years combing the Paris archives in an attempt to highlight both the devastation as well as the remarkable efforts toward reconstruction that occurred when the waters receded.

Chapter 16: What first drew your attention to the 1910 flood?

Jackson: Despite researching the history of Paris for many years, I had never heard about the flood until the summer of 2005 when I toured the Parisian sewers. There is a small historical display in one of the tunnels. Later that same year, Hurricane Katrina hit, and I realized that New Orleans was going through some of the same kinds of things that Paris had experienced in 1910. Suddenly the flood seemed timely and relevant to today’s world. Then I began to discover the hundreds of photographs of the flood from that era. They are remarkable documents, and the power of these images drew me further into this story.

Jackson: Despite researching the history of Paris for many years, I had never heard about the flood until the summer of 2005 when I toured the Parisian sewers. There is a small historical display in one of the tunnels. Later that same year, Hurricane Katrina hit, and I realized that New Orleans was going through some of the same kinds of things that Paris had experienced in 1910. Suddenly the flood seemed timely and relevant to today’s world. Then I began to discover the hundreds of photographs of the flood from that era. They are remarkable documents, and the power of these images drew me further into this story.

Chapter 16: Despite a decade of Parisian archival research and college-level teaching, you had never heard of the flood. Why has this particular disaster remained so obscure?

Jackson: I think that the flood has largely (although not entirely) been forgotten for several reasons. It was overshadowed by a much larger disaster four years later when World War I erupted. When people think about the turn of the twentieth century era, they remember the war rather than the flood. Because the damage from the flood was repaired relatively quickly, there are no physical traces to remind Parisians of the event. Markers on bridge supports and on a few streets around town show the level of the water’s height, but they are easily overlooked, especially if you’ve never heard of the flood. Many people collect postcards with flood photographs, but these images have turned the flood from a memorable disaster into a quaint historical episode. Everything looks “smaller” inside the frame of a postcard photo.

Chapter 16: You’re a professor of history at Rhodes College, which took in students displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Can you compare the flooding of New Orleans in 2005 to that of Paris in 1910?

Jackson: Like New Orleans, the flooding in Paris was widespread throughout the city, although certain areas were hit harder than others. Also as in New Orleans, the city’s infrastructure made the disaster worse. In Paris, the sewers and the subway carried water into neighborhoods where it couldn’t have gotten on its own, just as in New Orleans canals carried water through neighborhoods and flooded those areas when the levees broke. One of the biggest differences was in how people responded. In Paris, although the social fabric did stretch, it didn’t break. Most people rallied together and found ways to help one another. That happened in New Orleans too, but there were many more instances of human suffering because the city’s social networks were divided along lines of race and class. Parisians tended to overcome divisions of class, religion, and politics to save the city.

In Paris, although the social fabric did stretch, it didn’t break. Most people rallied together and found ways to help one another. That happened in New Orleans too, but there were many more instances of human suffering because the city’s social networks were divided along lines of race and class.

Chapter 16: Did you have contact with any students displaced by Katrina (or Katrina survivors in general)? If so, how did they influence your book?

Jackson: Several of my students from the Gulf Coast left Rhodes on short notice to go home and help their families. We also accepted students from Tulane and other New Orleans schools; I had two in one class that semester. They helped me think about how people respond to disaster because I found myself thinking about how to help them even though I couldn’t go to New Orleans. I also had a former student with whom I had worked closely [and] whose family lives in New Orleans. He moved back after the hurricane and worked for an urban planning firm on rebuilding the city. He and I co-authored a recent op-ed article for The Times-Picayune about how the city can continue to recover.

Chapter 16: Who, in your mind, were the greatest heroes of the 1910 flood? Who were its villains?

Jackson: The residents of Paris who pulled together were definitely the heroes. They found ways to rescue or provide relief for their families and neighbors. Shelters opened around Paris to house thousands of refugees. The government, the military, police, firefighters, the Red Cross, and the Catholic Church distributed aid across Paris. One wonderful photograph shows an elderly man putting a few coins into a collection box outside a government building. On the box, a sign announces that all money placed there would go to the flood victims. That image says a lot about the sense of togetherness which Parisians expressed during the flood.

There were other heroes too, including the police chief Louis Lépine, who coordinated much of the relief on the ground and crisscrossed Paris in knee-high boots making sure that hospitals were evacuated and fires put out.

The only people who might qualify as “villains” were the looters, although it’s hard to know much about them. In the years before the flood, some naive engineers hadn’t followed recommendations about how to build railway lines and retaining walls. I wouldn’t call them villains but rather people who thought so highly of their own abilities that they didn’t see their own limits.

Mythmaking is important to the aftermath of a disaster because it shapes how people remember the event and how they recover from it. We make myths about disasters to convince ourselves that we can overcome them again in the future.

Chapter 16: What long-term changes resulted from the flood and its aftermath? Are modern Parisians affected by the legacy of the flood of 1910 in ways they know nothing about?

Jackson: In the 1960s, the government built a series of reservoirs upstream from Paris (the “great lakes”) to take pressure off of the Seine in times of flood. Today’s flood emergency plan for Paris is based on the 1910 flood, so residents do have a strategy in case a similar disaster happens again. As a result, most Parisians don’t really need to think actively about flooding. The water still rises from time to time, but once the Seine falls again, most people’s anxieties vanish.

Chapter 16: You point out right away that floods—big, destructive floods—from the Seine have occurred regularly since humans sought to occupy its banks. By 1910, you suggest, Parisians falsely believed they’d tamed the river for good. Can you comment on human complacency in the face of natural disaster?

Jackson: The belief that humans can control nature is, in many ways, at the heart of the story of the 1910 flood because no one expected the Seine to overwhelm the city. It was an important part of the nineteenth-century faith in progress and the hope that science could make life consistently better, especially in Paris which had been extensively “modernized” in the 1860s. The events of the twentieth century would challenge that kind of nearly-unquestioning belief in the power of science, but we still rely every day on our ability to shape nature to our own ends regardless of the long-term consequences.

We also seem to need to forget disasters; otherwise cities might never be rebuilt after such a tragic event. Rebuilding is our way of once again reasserting control over our environment and showing our belief in unending progress. When we think back to disasters in the past, we often tell the story of how the disaster happened, but then we talk about how we fought our way back. Telling stories of recovery is just as crucial to the process of taming nature because it reinforces our belief that we are in control of our future.

We also seem to need to forget disasters; otherwise cities might never be rebuilt after such a tragic event. Rebuilding is our way of once again reasserting control over our environment and showing our belief in unending progress. When we think back to disasters in the past, we often tell the story of how the disaster happened, but then we talk about how we fought our way back. Telling stories of recovery is just as crucial to the process of taming nature because it reinforces our belief that we are in control of our future.

Chapter 16: Disaster researchers use the term “convergence” to describe the way people and resources combine in an altruistic urge to alleviate suffering after a crisis. Is this a universal phenomenon? Might it be a myth perpetuated by survivors, who are anxious to alleviate any guilt they feel?

Jackson: Mythmaking is important to the aftermath of a disaster because it shapes how people remember the event and how they recover from it. We make myths about disasters to convince ourselves that we can overcome them again in the future. But there are enough examples from disasters throughout history to suggest that “convergence” is a real phenomenon. Convergence is widespread during many disasters, but not universal. In places where social ties are weak, people can’t come together because they don’t see themselves as part of the same community. Or where the population is so devastated that victims outnumber non-victims, there is no one left to render assistance. That didn’t happen in Paris because there were still plenty of people who were not flooded out, and the government proved its ability to work effectively during a flood.

Chapter 16: This year marks the centennial of the flood. How will Paris mark the occasion? How will you?

Jackson: In 2010, there will be exhibitions of photographs and other documents from the 1910 flood, including one at the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, the city’s chief library about the history of the city. They’ve invited me to participate in a panel discussion. I’ll also be giving a talk at the American University of Paris on January 28, 2010, the exact 100th anniversary of the high water mark of the flood.

Jeffrey H. Jackson will read from Paris Under Water at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on January 19 at 6 p.m.; at Vanderbilt University on January 21 at 4 p.m. in the Fireside Room of the Peabody Library; and at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on January 21 at 7 p.m.