Profound Activities of the Mind

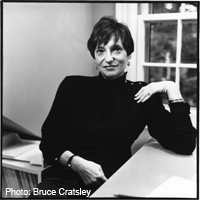

Prior to her Memphis appearance, Shakespearean scholar Marjorie Garber talks with Chapter 16 about the pleasures of reading and the value of the humanities

According to Marjorie Garber, the way we read Shakespeare’s plays tells us as much about ourselves as it does about the Bard himself. Garber’s books on Shakespeare, including Shakespeare and Modern Culture (2008) and Shakespeare After All (2004), identify issues raised by the plays and assess ways that each has been interpreted (and misinterpreted), but they leave the question of the plays’ ultimate meaning to readers. Garber, the William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of English and Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University, offers to no easy or reductive answers to the perennial questions regarding Shakespeare and his plays. Her scholarship surveys the ways in which those questions have changed over time and how each generation—and each culture—answers them differently.

In her recent books, Loaded Words (2012) and The Use and Abuse of Literature (2011), Garber has expanded her inquiry to explore the changing role of the humanities in universities and the value of literature in contemporary culture. Her intellectual passions encompass a wide array of questions—the evolution of college curricula, the changing meaning of cultural literacy, and the function of literature, to name just a few—but keep circling back to her fundamental belief in the importance of questioning. Garber continually wonders whether we are asking the right question (to ask, for example, “What use is the humanities?,” strikes her as unproductive) and endeavors to frame each issue in ways that lead in interesting directions—not to final conclusions, that is, but to new avenues of investigation.

In her recent books, Loaded Words (2012) and The Use and Abuse of Literature (2011), Garber has expanded her inquiry to explore the changing role of the humanities in universities and the value of literature in contemporary culture. Her intellectual passions encompass a wide array of questions—the evolution of college curricula, the changing meaning of cultural literacy, and the function of literature, to name just a few—but keep circling back to her fundamental belief in the importance of questioning. Garber continually wonders whether we are asking the right question (to ask, for example, “What use is the humanities?,” strikes her as unproductive) and endeavors to frame each issue in ways that lead in interesting directions—not to final conclusions, that is, but to new avenues of investigation.

Prior to her appearance at Rhodes College in Memphis on March 27, Garber answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You have studied and taught Shakespeare for decades and keep finding new ways to make his work interesting. Any advice for teachers, scholars, directors, and actors about how to keep Shakespeare fresh in their own minds even after years of exposure to his plays?

Marjorie Garber: 1) Reread. Never take anything you know for granted. Every time I read one of the plays I find something new, something I’ve overlooked, something that surprises me. And nothing is more pleasurable than reading these plays—except reading them again. 2) Go to the theater. Every production is an interpretation, and every production, amateur or professional, will contain some moment that is provocative, revealing, gratifying, or disturbing, putting the work into a new perspective. 3) Find a phrase, speech, or dialogue that strikes you as telling and pertinent to events in the world today. What is often called Shakespeare’s “timelessness” is an uncanny way of being fresh and “timely” for every era (and every global location).

Chapter 16: In Shakespeare and Modern Culture, you argue that readings of Shakespeare’s plays are always both “right” and “wrong,” though in your chapter on Othello you expose some invidious mis-uses of Iago. Is there a “right” way to apply Iago’s unmotivated malignity—for example, to terrorists?

Garber: Iago’s “motiveless malignity”—this phrase from Samuel Taylor Coleridge has had a long run, critically speaking, but it may be time to retire it for a while because it has taken on a life of its own. In the play Iago has plenty of motives, some expressed, some unexpressed, some persuasive and some not. In particular it is Iago’s peculiar combination of love and hatred, intertwined in his attitude toward Othello, that leads him in an economical masterstroke to displace both his rivals—Desdemona and Cassio—to become Othello’s “own forever.” I’ve discussed this in Shakespeare After All and in other books.

Garber: Iago’s “motiveless malignity”—this phrase from Samuel Taylor Coleridge has had a long run, critically speaking, but it may be time to retire it for a while because it has taken on a life of its own. In the play Iago has plenty of motives, some expressed, some unexpressed, some persuasive and some not. In particular it is Iago’s peculiar combination of love and hatred, intertwined in his attitude toward Othello, that leads him in an economical masterstroke to displace both his rivals—Desdemona and Cassio—to become Othello’s “own forever.” I’ve discussed this in Shakespeare After All and in other books.

You ask about “applying” his malignity, by which I think perhaps you might mean using it as an analogy to some other instance of seriously bad action, whether in literature, history, or modernity. But it’s not the malignity itself that is usually “applied” by journalists, pundits, and others—instead it’s the incantatory name of Iago, used as a label and a piece of cultural shorthand.

Chapter 16: You have said that what ties together the topics of your books—which cover dogs, real estate, and cross-dressing, in addition to Shakespeare—is love, namely the love you have for the subjects. How do you decide on the focus of your next project? And will you tell us what you are working on currently?

Garber: What I think I actually said, and in any case certainly what I meant, was that the topics of four of my books, while apparently quite disparate, had in common the theme of love in its many forms. The books then under discussion were Vested Interests (1991), about cross-dressing and cultural anxiety, Vice Versa (1996), about bisexuality and the erotics of everyday life, Dog Love (2008), about dogs and how they make us human, and Academic Instincts (2001), about literature and the humanities. These may seem very different subject areas, but my interest in them, and the claims I made in each book, turned out to be cognate. I didn’t set out to do this programmatically. Rather I looked back at what I had said and argued, and was struck by what this work had in common.

My approach to topics tends to be allusive, peripatetic, and metonymic, moving from idea to idea, from text to text, from thought to thought. Sometimes my projects are “occasional”—that is, they come to me through an invitation to speak or write, often on topics or issues I hadn’t previously addressed or researched. Some examples would include my recent essay on Ovid in Critical Inquiry (which began as an MLA paper for a panel on Ovid, Then and Now) and a piece called “Mad Lib” (published in my collection Loaded Words) which developed as a result of an invitation to participate in a conference on a new translation of Foucault’s History of Madness.

One of the great pleasures for a writer, I think, is to be asked to address new questions, questions that come from other people and other contexts. (I think all teachers really long at some point to be students.) The little piece I wrote on Wikileaks for Foreign Policy magazine was another example. But of course many of my larger projects have been ones I’ve been thinking about for years, even if they begin with a smaller piece and grow into a book. And there are books I’ve written that have begun as lectures for students in the classroom, including two of my Shakespeare books, Shakespeare After All and Shakespeare and Modern Culture. As for current projects, I do have some, but I never really discuss them when they are still in process, though I’d be glad to do so if/when they appear in print.

Chapter 16: Speaking of love, what role should aesthetic pleasure take in reading and in the classroom? Can teachers lead students to enjoy the beauty of literature, or is that kind of love an entirely private, subjective matter?

Chapter 16: Speaking of love, what role should aesthetic pleasure take in reading and in the classroom? Can teachers lead students to enjoy the beauty of literature, or is that kind of love an entirely private, subjective matter?

Garber: Aesthetic pleasure is—do I need to say “of course”?—one of the chief reasons to read, think, discuss, and indeed quote or memorize works of literature. A teacher’s or critic’s enthusiasm can communicate itself to students and readers, and can open up new texts and authors. Having said that, though, I’d also say that the authors people say they “love” are sometimes the authors about whom they don’t want to read criticism and theory, or do textual analysis. (Two of these are Shakespeare and Jane Austen, both of whom I have great pleasure in teaching.) But somehow the idea has crept in that the analysis of literary works diminishes the pleasure of the reader. For me the opposite is the case. Like every production or performance, every reading is an interpretation. The more we look at language, characterization, design, structure, the more we can see of the ways the poem or play or novel works. As has often been noted, it’s not what a work means but how it means that concerns literature and the humanities. Not only is productive and provocative analysis not inconsistent with the “love of literature,” it is—for me at least—the essence of, and an expression of, that love.

Chapter 16: In your essay “After the Humanities,” you make a number of provocative proposals for how the liberal arts should change in order to keep up with the times. What do you believe is the most important role the humanities play in society as a whole?

Garber: A few years ago I was asked to speak in a Presidential Forum for the Modern Language Association on the topic of “The Humanities and the World.” Other speakers on the program talked about literature and law, about the making of films from literary works, about anthropology and society. Reflecting on the topic, I decided instead to insist that the classroom and the lecture hall were very much part of “the world,” and that if we accede to the idea that the world is to be found only outside the classroom we will pretty much give up the central value and importance of “the humanities” and their claim to our attention. (The essay I wrote for this occasion is called “Good to Think With,” and is also in Loaded Words.) The humanities are not just in society; they are society. I sometimes joke to my scientist friends that the humanities are what they are saving the world for.

Chapter 16: In The Use and Abuse of Literature and elsewhere, you argue that the value of literature lies precisely in its “uselessness,” but you aver that reading can also have salutary “cultural effects.” Would you discuss one such effect and how readers can cultivate it?

Garber: When I talk about “uselessness,” a deliberately provocative term, I am intending to resist the arguments for instrumentality that have been marshalled by some writers wishing to “defend” the humanities. It seems as if scholars in the humanities are now constantly being asked to explain how the humanities be used, or made useful, in the world today. (The title of my book derives from Nietzsche’s famous essay, “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life.”) I don’t think literature makes us better people, and I don’t think novels (or plays, or poems) are a particularly efficient or effective way of conveying, or inculcating, moral or ethical ideas. We don’t need five acts of Macbeth to deliver the message that it’s not good idea to kill the king, or to take over a country by force or guile. (And we don’t need a whole novel like Pride and Prejudice to deliver the message that love is sometimes a matter of thinking twice). A “message” is precisely the wrong thing to look for in literature (or painting or sculpture or film). Once you boil down the subtleties of language, plot, character, and structure to a one-sentence macro, the size of a tweet, you have left behind, and pretty much left out, the value and pleasure and impact of art.

Garber: When I talk about “uselessness,” a deliberately provocative term, I am intending to resist the arguments for instrumentality that have been marshalled by some writers wishing to “defend” the humanities. It seems as if scholars in the humanities are now constantly being asked to explain how the humanities be used, or made useful, in the world today. (The title of my book derives from Nietzsche’s famous essay, “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life.”) I don’t think literature makes us better people, and I don’t think novels (or plays, or poems) are a particularly efficient or effective way of conveying, or inculcating, moral or ethical ideas. We don’t need five acts of Macbeth to deliver the message that it’s not good idea to kill the king, or to take over a country by force or guile. (And we don’t need a whole novel like Pride and Prejudice to deliver the message that love is sometimes a matter of thinking twice). A “message” is precisely the wrong thing to look for in literature (or painting or sculpture or film). Once you boil down the subtleties of language, plot, character, and structure to a one-sentence macro, the size of a tweet, you have left behind, and pretty much left out, the value and pleasure and impact of art.

We don’t need to defend the humanities by agreeing that they have a “use,” whether educational, cultural, moral, ethical or social. This instrumental way of thinking about art is itself defensive, and misses the point. The humanities, properly understood, need no defense since they include and encompass all ways of thinking, knowing, and feeling. As for salutary cultural effects, the cultural effect of reading (and of art-making, and of philosophizing, and of literature and cultural theory) is itself the production of culture. How salutary this will prove to be depends upon the commitment we make to the central importance of these activities, not as “recreation” or “leisure time” or even as an all-purpose “liberal arts education” before the serious work of career-building, but rather as the very way we encounter the minds of others and the profound beauty and terror of language and—through language—of the world.

Chapter 16: The title essay of Loaded Words traces the changing cultural cachet of terms (“knowledge,” “management,” “information”) that at any given historical moment we tend to regard as self-evident. Can you discuss an example of a word whose meaning has accrued new weight from recent cultural or political events?

Garber: A couple of years ago the word might have been “occupy,” which still has a lot of new resonance as a result of the Occupy movements and their aftermath. Thinking quickly about the present day, it occurs to me that one such word is “equality.” Both the women’s suffrage movement (which led to the nickname of Wyoming as the Equality State, since it was, in 1869, the first state to grant women the right to vote) and the civil-rights movement made good use of the term, as, needless to say, did the French Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, and the U.S. Bill of Rights. Today, though, “equality” is often understood to refer to LGBT issues. The phrase “marriage equality” is now regularly used as the indicative term for legalizing gay marriage (rather than, for example, denoting the equality within a marriage of the marital partners). Recent headlines in The New York Times thus included “Toward Marriage Equality in New Jersey,” “New Victories for Marriage Equality,” and of course, “Scalia Has Seen the Future, and Its Name is Marriage Equality.” Compared with much more contestatory terms, like “gay marriage” or “same-sex marriage,” “marriage equality” generalizes and universalizes the right to marry. Like “choice,” when it was first used as a shorthand term for abortion rights, “equality” puts the onus on the resisters to explain why they oppose a fundamental American social principle.

Chapter 16: In Loaded Words, you argue that uncertainty should be considered a positive value, not simply a state that must be rectified with clear answers. Why is doubt more important than certainty?

Garber: I’d prefer to describe this as the value of flexible and historically contingent thinking as contrasted with dogmatism and sloganeering. In an essay called “Knowledge and Belief,” published in Critical Inquiry in 2005, I tried to put in question the “certainty” that those two words seem to imply, and the unquestioning value with which they are sometimes charged. If we consider some alternatives to “I know” or “I am certain,” like “I think,” or “I imagine” or “I wonder,” we might be able to see “uncertainty” as a space of possibility and inquiry rather than a mistaken refusal to accept a certain answer. A position of uncertainty can be perfectly clear; it might include ambiguity, ambivalence, or openness to scientific progress. (The world was once “certainly” flat, then it was “certainly” round; the earth was once “certainly” at the center of the universe, then it became “certain” that it revolved around the sun; witches once “certainly” caused illness and the failure of crops.)

In literary studies we praise the richness of words that have two or more semantic meanings, whether we call this richness of language punning, literary ambiguity, or historical specificity. This fluidity of reference is poetry, not (merely) uncertainty. Counterfactuals and “what-ifs” have played an important part in law, political theory, and philosophy. Sigmund Freud begins a section of Beyond the Pleasure Principle with the disarming phrase, “What follows is speculation,” and the pages that follow are especially brilliant and challenging. Out of such speculations come theory and imagination, the most profound activities of the human mind.

Marjorie Garber will speak at Rhodes College in Memphis on March 27, 2014, at 7 p.m. Her talk, “Occupy Shakespeare: Shakespeare and/in the Humanities,” is free and open to the public.