Ethnic Identity Theft

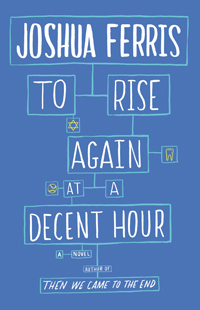

In Joshua Ferris’s To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, cyber-stalking leads to personal revelation

Joshua Ferris is a serious author who built his reputation on being funny. Reviews of his first novel, Then We Came to the End, reliably commented on its humor in dissecting corporate mores in the age of layoffs. But beneath its sit-com wit is a deeply felt angst about the meaning of existence when the self seems to be a function of the marketplace. Ferris’s second novel, The Unnamed, explored similarly dark themes—the nature of compulsion and the mystery of human agency—but didn’t leaven the text with punch lines. Fans of Then We Came to the End will be pleased that Ferris’s new novel, To Rise Again at a Decent Hour (which last week was shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize ), returns to the comedy that attracted a wide readership, though once again darkness remains a constant presence in the book.

Light and dark elements combine in every sequence of the new novel. The protagonist, Paul O’Rourke, is a successful Manhattan dentist whose practice is in perfect working order but whose personal life is an unqualified mess. By day his Upper East Side exam rooms are filled with satisfied patients who count on him to correct the deleterious effects of their own negligence, a task Paul is perfectly suited to perform. At night, though, he fills the empty hours by drinking excessively and following the Boston Red Sox obsessively. His ex-girlfriend, the beautiful Connie, continues to work in his office as his business manager, an arrangement that gives him little opportunity to get over their breakup. Walking the streets of New York, playing a private game he calls “Things Could Be Worse”—“I could be that guy. Parading by everywhere were the disfigured, the destitute, the hideously ugly, the walking weeping, the self-scarred, the unappeasably pissed off”—brings Paul negligible comfort. Just below the surface, too, remains the memory of his manic-depressive father’s suicide three decades earlier.

Light and dark elements combine in every sequence of the new novel. The protagonist, Paul O’Rourke, is a successful Manhattan dentist whose practice is in perfect working order but whose personal life is an unqualified mess. By day his Upper East Side exam rooms are filled with satisfied patients who count on him to correct the deleterious effects of their own negligence, a task Paul is perfectly suited to perform. At night, though, he fills the empty hours by drinking excessively and following the Boston Red Sox obsessively. His ex-girlfriend, the beautiful Connie, continues to work in his office as his business manager, an arrangement that gives him little opportunity to get over their breakup. Walking the streets of New York, playing a private game he calls “Things Could Be Worse”—“I could be that guy. Parading by everywhere were the disfigured, the destitute, the hideously ugly, the walking weeping, the self-scarred, the unappeasably pissed off”—brings Paul negligible comfort. Just below the surface, too, remains the memory of his manic-depressive father’s suicide three decades earlier.

Into this already tumultuous emotional life comes a new problem: someone has assumed Paul’s identity and begun cultivating a presence on social media, a territory Paul has studiously avoided. Having an unauthorized website created in his name is troubling enough; having the otherwise accurate and professional-looking website claim that Paul is a member of an obscure ancient sect is nothing short of Kafkaesque. “Dr. Paul C. O’Rourke” purports to be an Ulm, the genetic descendants of the Amalekites, enemies of the Jews and long thought to have been exterminated in accordance with three Old Testament mitzvoth.

And yet even this patent falsity includes echoes of Paul’s actual past. During the Bronze Age, when most other ethnic groups “were still spooked by a gathering of dark clouds” and prayed to idols, the Ulms’ sole commandment was to disbelieve in God, and as an atheist himself Paul finds this supposed religion a little too tailor-made to his predisposition. Nevertheless, he longs for a spiritual tradition and has before been guilty of identity co-optation involving religious beliefs he doesn’t share. His search to find the truth of his ethnic heritage—and to discover the motives behind this hoax—becomes a search for himself in a more personal sense, as well.

And yet even this patent falsity includes echoes of Paul’s actual past. During the Bronze Age, when most other ethnic groups “were still spooked by a gathering of dark clouds” and prayed to idols, the Ulms’ sole commandment was to disbelieve in God, and as an atheist himself Paul finds this supposed religion a little too tailor-made to his predisposition. Nevertheless, he longs for a spiritual tradition and has before been guilty of identity co-optation involving religious beliefs he doesn’t share. His search to find the truth of his ethnic heritage—and to discover the motives behind this hoax—becomes a search for himself in a more personal sense, as well.

Even as the novel tracks Paul’s investigation into the flickering reality of the Ulms, the whodunit plot becomes less compelling than Ferris’s depiction of a character suffering from depression. Paul understands that he is his own worst enemy: “Of course I alienate myself from society. It’s the only way I know of not being constantly reminded of all the ways I’m alienated from society.” The story of how he begins to move, haltingly, toward a future that isn’t haunted by neurosis is equal parts moving and compelling.

To Rise Again at a Decent Hour is also deliciously funny, with the kind of slow-building comedy that begins by eliciting snickers and ends with guffaws. If To Rise Again doesn’t have quite the hopeful uplift of Then We Came, neither does it have the downbeat fatalism of The Unnamed. With Paul O’Rourke, Ferris has created a character swarmed by demons but struggling to find a path to the light. The passage from which the title derives captures this mixed tone. After a night of solitary drinking that ends with Paul passed out on his Brooklyn balcony, he wakes at a rare New York hour when not a single human being is stirring. The quiet and the loneliness strike Paul as terrifying: “I felt so forgotten, so passed over, so left behind, so lost out. I was sure not only that everything worth doing had already been done while I was asleep but also that, now that I was awake, there was no longer anything worth doing.”

In the next moment, though, he demonstrates an awareness of how one can act meaningfully—or, at a minimum, pleasurably—simply by joining life’s everyday pageant. He imagines what he would do if the “strollers and lovers” who had been enjoying Prospect Park a few hours earlier returned “so that I might have another chance to stroll alongside them, to look out in wonder at the skyline, to lick carefully at the edges of my ice cream, and after a while, to leave the Promenade, off to bed for a good night’s sleep … and then to rise again at a decent hour, to walk the Promenade in the light of a new morning, eating a little pastry for breakfast and having coffee on one of the benches while looking out at the brightened waters.” Paul O’Rourke exists in a cavern of despair, but Ferris makes it clear that he can find a way out if he simply continues to seek these sources of light.

[This review originally appeared at Chapter 16 on September 15, 2014.]

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford University as an undergraduate. He later returned to Austin, where he earned a Ph.D. in modern fiction from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.