A Stolen Life

Zora Neale Hurston relates the stories of an extraordinary survivor of the transatlantic slave trade

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review was originally published on September 5, 2018.

***

The young woman and the old man shared clingstone peaches. She brought him a Virginia ham and a ripe watermelon. Once they feasted on a “marvelous mess of blue crabs.” When the old man felt like it, he told her stories of his life—of Africa, of the Middle Passage, of slavery and freedom, of resilience and heartache. Nearly a century later, we have Barracoon, his remarkable and painful memoir.

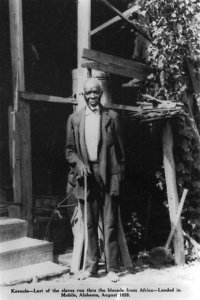

The old man was Oluale Kossola, known in the United States as Cudjo Lewis. He came to America in 1860 on the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to reach American shores. By 1927, he was the final survivor of the transatlantic slave trade.

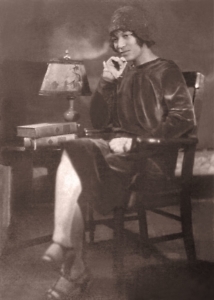

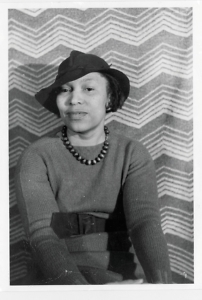

The young woman was Zora Neale Hurston, who had not yet published any of her classic books, such as Their Eyes Were Watching God. Sent by her academic mentor, the anthropologist Franz Boas, and supported by Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, she conducted research in Florida and Alabama. During the three months she spent in Plateau, a suburb of Mobile, she heard the tales of Cudjo Lewis.

Lewis’s voice, with its particular diction and rhythm, occupies most of the space in Barracoon. He relates his youth as an Isha Yoruba in West Africa, before being captured by the female warriors of Dahomey. He endured a slave pen, or barracoon, near the Bight of Benin, and then the terrible hold of the Clotilda as it crossed the Atlantic. Hidden in the swamps up the Alabama River, the slaves were divided among the merchants conducting this international commerce in human flesh, which had been banned by the Constitution since 1807.

“We cry for home,” recalls Lewis. “We took away from our people. We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now ‘dey part us from one ‘nother. Derefore we cry. We cain help but cry. . . . I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama. Oh Lor’!” At this point, Hurston makes one of her rare but evocative interludes, describing how Lewis quieted. Then, she writes, “I saw the old sorrow seep away from his eyes and the present take its place.”

In their classic form, the personal narratives of nineteenth-century African Americans focus on the horrors of slavery, simultaneously painting a heroic self-portrait of the men and women who claim their place in the democratic tradition. Barracoon is something else, a lamentation for a lost world, for a life stolen from “de Affica soil.”

Lewis tells the story of his emancipation upon the end of the Civil War and his place in founding Africatown, a small village populated mostly by freedpeople who had arrived on the Clotilda. This slim book is most affecting, however, in relating his personal trials. He and his wife had six children, but they all died young. One was shot in the throat by a white deputy sheriff who went unpunished and became a pastor. Others got sick. His wife died, too.

As Alice Walker writes in the book’s foreword, “We see a man so lonely for Africa, so lonely for his family, we are struck with the realization that he is naming something we ourselves work hard to avoid: how lonely we are too in this still foreign land: lonely for our true culture, our people, our singular connection to a specific understanding of the Universe.”

Barracoon was not published in its time. Viking Press wanted the language converted to standard English, but Hurston insisted on Lewis’s authentic voice. Moreover, the manuscript’s accounts of atrocities within Africa, as well as the tensions between America-born and Africa-born blacks, did not square with the emerging ideals of the “New Negro.” The manuscript sat in an archive at Howard University for decades.

Now, with expert editing and context-setting by scholar Deborah G. Plant, this collaboration between an old man and a young woman is available to all. They ate their peaches, they told his story, and they have enriched our understandings of our history and ourselves.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.