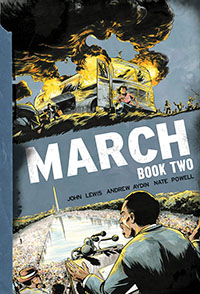

March 7, 2015, marked the fiftieth anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” the day civil-rights marchers were beaten by police as they crossed the Edmund Pettus bridge into Selma—an event that became a catalyst for passage of the Voting Rights Act and served as a lasting metaphor for the entire civil-rights movement. One of the demonstrators attacked that day was Representative John Lewis, Democratic congressman from Georgia. At the anniversary celebration of the conflict earlier this month, he marched across the bridge arm-in-arm with President Barack Obama.

As a young follower of Martin Luther King Jr. and the only surviving speaker from the March on Washington—where King gave his now-iconic “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—Lewis is forever linked with the American civil-rights movement. In 2013, his graphic memoir, March: Book One, the first in a projected trilogy, chronicled the lunch-counter sit-ins that Lewis and other Nashville college students began in 1958. March: Book Two begins in Nashville in 1960 and follows the growing movements there that ultimately led thousands of students to become “Freedom Riders,” a daring plan to integrate bus lines throughout the South.

As a young follower of Martin Luther King Jr. and the only surviving speaker from the March on Washington—where King gave his now-iconic “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—Lewis is forever linked with the American civil-rights movement. In 2013, his graphic memoir, March: Book One, the first in a projected trilogy, chronicled the lunch-counter sit-ins that Lewis and other Nashville college students began in 1958. March: Book Two begins in Nashville in 1960 and follows the growing movements there that ultimately led thousands of students to become “Freedom Riders,” a daring plan to integrate bus lines throughout the South.

Just as the first volume does, March: Book Two opens with Lewis’s activities on the morning of Obama’s 2009 inauguration as the first African-American president. This reference point reappears at several key moments in the story, reinforcing the very different—and far more dangerous—world Lewis inhabited in the early 1960s. As groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) gain national attention—first from sit-ins at lunch counters and “stand-ins” at segregated movie theaters in downtown Nashville, and then from the efforts to integrate bus lines—responses to the protests become increasingly violent.

The trilogy is a collaboration among Lewis; Andrew Aydin, Lewis’s former congressional press officer and a self-proclaimed comics geek; and Nate Powell, the talented artist behind the graphic novels Any Empire and Swallow Me Whole. With this stunning volume, the trio may have surpassed even the widely acclaimed first installment of the trilogy.

The cinematic style of Powell’s artwork dovetails with Aydin’s narrative pacing to create a work that resonates emotionally, with images lingering in the reader’s mind as a series of unforgettable moments. Reading March: Book Two is an experience more akin to watching a film like Selma or Twelve Years a Slave than to reading a traditional memoir. Powell captures Lewis’s personal recollections through subtle visual cues: no two comic panels are drawn the same size, or placed in the regular alignment common to traditional comic books or even literary graphic memoirs like Maus or Fun Home. Instead, words and images often break through the borders of panels; characters explode across the page in fragments of remembered action. The heavy contrast of light and dark elements, along with extreme angles and perspectives, have the reader roiling as if assaulted by fire hoses and police dogs, or sitting in an intense strategy session with CORE leaders. It is a visual, visceral tour de force.

The cinematic style of Powell’s artwork dovetails with Aydin’s narrative pacing to create a work that resonates emotionally, with images lingering in the reader’s mind as a series of unforgettable moments. Reading March: Book Two is an experience more akin to watching a film like Selma or Twelve Years a Slave than to reading a traditional memoir. Powell captures Lewis’s personal recollections through subtle visual cues: no two comic panels are drawn the same size, or placed in the regular alignment common to traditional comic books or even literary graphic memoirs like Maus or Fun Home. Instead, words and images often break through the borders of panels; characters explode across the page in fragments of remembered action. The heavy contrast of light and dark elements, along with extreme angles and perspectives, have the reader roiling as if assaulted by fire hoses and police dogs, or sitting in an intense strategy session with CORE leaders. It is a visual, visceral tour de force.

A key plot element of the book is Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s slow and often grudging acceptance of the strategies employed by the student protesters. While Kennedy and King were ostensible allies, Lewis considered the legislation Kennedy supported to be weak and watered down, and Kennedy disapproved of student protest actions that were almost certain to lead to violent reaction in the South. One Kennedy aide who attempts to protect the freedom riders, and who seems to carry some of the credit for eventually swaying the attorney general to the side of the protesters, is Nashville native John Seigenthaler. The book is dedicated to Seigenthaler, who died in 2014 after becoming a legendary journalist and champion of free speech.

In one memorable scene in March: Book Two, Seigenthaler, who is white, stands before an angry mob in Montgomery that has surrounded the bus from which Lewis and other riders have just fled. “My name’s John Seigenthaler,” he proclaims. “I’m here on direct orders from the—” at which point a blow from a billy club slams him to the pavement.

In one memorable scene in March: Book Two, Seigenthaler, who is white, stands before an angry mob in Montgomery that has surrounded the bus from which Lewis and other riders have just fled. “My name’s John Seigenthaler,” he proclaims. “I’m here on direct orders from the—” at which point a blow from a billy club slams him to the pavement.

As the mob moves in for the kill, only a pistol fired by Alabama safety officer Floyd Mann saves the future journalist and the frightened future congressman beside him. “I’ll shoot the next man that hits him,” Mann says. “They’ll be no killing here today.” It is one of many scenes of righteous bravery that cannot help but have readers cheering.

March: Book Two moves beyond a visual depiction of history; it represents a triumph of graphic storytelling as a medium for memoir, of visual narrative elevated to highest art. As when Lewis and Obama crossed together into Selma, it creates a bridge by which future generations can understand the struggles of the past.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a forthcoming textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.

Tagged: Children & YA, John Lewis, Nonfiction