Marching Tall

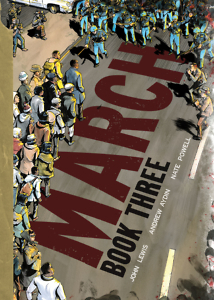

The third volume of John Lewis’s memoir of the civil-rights movement may be the best yet

Five days before the November 8 election, John Lewis, Democratic congressman from Georgia, wrote on Twitter, “I’ve marched, protested, been beaten and arrested—all for the right to vote. Friends of mine gave their lives. Honor their sacrifice. Vote.” The tweet was accompanied by a newspaper photo of Lewis, young and bloodied, being dragged away from a protest by three policemen. In July, Lewis—with his co-authors, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell—attended the San Diego Comic-Con to accept an Eisner Award, the Oscar of the comics industry, for March: Book Two, the second volume of their graphic nonfiction trilogy, which delivers a powerful memoir of Lewis’s role in the American civil-rights movement.

That same week the trilogy’s final volume, March: Book Three, was published in a first printing that sold out in less than a month. For much of the fall all three books have filled the top three spots of The New York Times bestseller list for softcover graphic books. Amid this commercial and critical success, Lewis will be in Nashville this weekend to accept the Nashville Public Library Literary Award. In Book Three, he describes his very personal role in the events that led to passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. It a story that infuses his recently tweeted photograph with vivid and heart-rending humanity.

As with the first two volumes, Book Three moves forward and backward in time. This book is framed by the day that has served as a refrain in all three volumes: January 20, 2009—the inauguration of the first African American president. Lewis’s own actions that day advance in scenes that provide relief from the violence and hatred that fill so many of the book’s pages. Moving from early 1963 through the summer of 1965, the story reaches its climax on the same day that opened the trilogy: March 7, 1965—“Bloody Sunday”—in Selma, Alabama.

That day Lewis left the Edmund Pettus Bridge with a serious skull fracture, but the events in Selma sped the stalled passage of the Voting Rights Act. Along the way, amid scenes of increasing violence, Lewis chronicles his internal struggles with Martin Luther King Jr., and other leaders of the movement, over strategy and methods, as well as a growing rift within the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a group he had helped to found in 1960. The story concludes at what Lewis calls “the last day of the movement as I knew it”—a signing ceremony for the Voting Rights Act in the U.S. Capitol—before returning to the frame narrative on the day after President Obama’s first inauguration. It is a surprisingly emotional payoff that has been building, it turns out, through all three books.

Book Three comes within a few pages of doubling the length of Book One, and it represents the full maturity and growing sophistication of the authorial team of Lewis, Aydin, and Powell. “I love flipping through Book Two after I flip through Book One,” Powell said in an interview, as he was still drawing Book Three. “To me it’s a very different book. It shows a kind of collaborative maturity.”

Repeated visual elements and themes give the story a unity that may pass unnoticed by many readers—especially increasing numbers of schoolchildren in districts that have adopted the books as required reading. One example is a symbolic device that becomes increasingly important as the trilogy progresses: a ringing telephone, which first appears in Book One as the congressman dresses to attend the Obama inauguration. By the end of Book Two, the device has become literally explosive, connected to a horrific bombing that sets the stage for Book Three. And a ringing telephone in Book Three hints that the “trilogy” may include other books yet to come.

Repeated visual elements and themes give the story a unity that may pass unnoticed by many readers—especially increasing numbers of schoolchildren in districts that have adopted the books as required reading. One example is a symbolic device that becomes increasingly important as the trilogy progresses: a ringing telephone, which first appears in Book One as the congressman dresses to attend the Obama inauguration. By the end of Book Two, the device has become literally explosive, connected to a horrific bombing that sets the stage for Book Three. And a ringing telephone in Book Three hints that the “trilogy” may include other books yet to come.

The subconscious effect of such devices adds to moments of soaring emotion as Lewis’s story touches truly historic events within the life of a single man. And each book lives up to the dedication line that all three volumes share: “To the past and future children of the movement.”

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.