Painting the Paradise That Used to Be

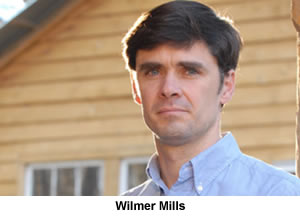

A new collection showcases the poetry of the late Wilmer Mills

Poet Wilmer Mills died of liver cancer in 2011 at the age of forty-one, only two months after his diagnosis. He left behind grieving friends and family members, along with scores of beautifully crafted poems. His wife, Kathryn Oliver Mills, served as editor of his new collection, Selected Poems. In an afterword, she lists the many and varied talents of her accomplished husband: farmer, carpenter, singer/songwriter, craftsman, baker, teacher, painter, and most passionately, poet. “Wil was a renaissance man not only for his diverse creative talents,” she writes, “but also … for how his life gave shape to his art, and his art gave shape to his life.” This is a poet who writes from specific, hands-on experience but who also sees beyond the ordinary to touch what is timeless in each act.

Selected Poems is divided into four roughly chronological sections. The first includes poems from Mills’s previously published book, Light for the Orphans (Storyline Press, 2002). This section encompasses his boyhood in Louisiana and in Brazil, where his parents were missionaries, through high school in Chattanooga and college at Sewanee. The two middle sections feature the poems he assembled for his unpublished volumes, Arriving on Time and The Heart’s Arithmetic. Many of them relate to courtship, marriage, and parenthood. The final section of the book, “The World That Isn’t There,” showcases poems Mills wrote near the end of his life.

Selected Poems is divided into four roughly chronological sections. The first includes poems from Mills’s previously published book, Light for the Orphans (Storyline Press, 2002). This section encompasses his boyhood in Louisiana and in Brazil, where his parents were missionaries, through high school in Chattanooga and college at Sewanee. The two middle sections feature the poems he assembled for his unpublished volumes, Arriving on Time and The Heart’s Arithmetic. Many of them relate to courtship, marriage, and parenthood. The final section of the book, “The World That Isn’t There,” showcases poems Mills wrote near the end of his life.

Coming to terms with the past is a common theme for Mills, especially in the poems of the first section. In the charming “Morning Song,” the poet remembers his mother singing over her kitchen chores. The music and the familiar kitchen sounds combine to create a kind of rhythm that gradually and gently rouses her family: “The house becomes her instrument / And we, like sluggish bees, get up in turn, / Charmed out of sleep by her sung disenchantment.”

In the six-stanza “Rain,” the narrator helps his aged grandfather plow a new garden, realizing that their time of working together will end as his grandfather’s health deteriorates. As they finish plowing, there is a sudden downpour, and the poet’s senses come alive as he takes in every aspect of the day, hoping to remember it forever: the plow handles are “smooth as bone,” he watches the rain “cascade like melted glass,” and he smells “sweet horse feed, hay, Bag Balm, and leather soap,” as he waits out the storm in his grandfather’s memory-filled barn.

The second section continues this focus on the past while also looking forward to the future. In poems like “A Letter to Myself as a Young Man,” “The Flower Beds of War,” and “Thanksgiving on the Gulf,” Mills considers the awkwardness of youth, the legacy of war, and the havoc wreaked by natural disaster. But the joyful center of this section is the poem Mills wrote for his wife, the ten-part “Stanzas for Kathryn.” In this selection, Mills uses the metaphor of a dance to embody the image of a growing family within the shelter of their home.

Our lives continue at a frantic pace

As if we thought to win the human race

By turning in circles in sickness and in health.

But it’s a dance, in poverty or wealth,

That funnels our freedom if we learn the form

And love the steps that turn us through the storm.

The third section includes poems about Mills’s son (“Benjamin Shooting Skeet”) and daughter (“Naming Our Daughter”), but once again it is time—specifically its ability to effect both good and evil in the life of a human being—that seems to preoccupy the poet’s thoughts. In “From Lookout Mountain at Night,” Mills imagines his son after his own death.

A memory is like a lack of time,

And time is like a dream I can’t recall,

And Metaphor is how the three are joined,

And all of them are where my son will be

When I am gone.

Mills was a lifelong Christian, but he often found it difficult to inhabit that tension between the fallen present and the promise of future glory. As his wife explains, “Wil knew very well that faith in life and God balances on a knife’s edge.” In “Fallen Fruit,” written in response to the death of Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman, Mills considers his children’s understanding of the world:

I can’t protect them; they were bound to see.

The Fall was knowing what it meant ‘to stand’

Then painting the paradise that used to be

In language that could raise it from the sand.

Thus the end of Eden foreshadows childhood’s end, and perhaps the poet’s own death—each capable of being redeemed through the memories of those who remain. Wilmer Mills’s clear-eyed vision of this world in all its heart-breaking beauty—as well as his hope in the next—is a gift with the power to resonate long after his thoughtful book is closed.

To read an essay Wilmer Mills wrote near the end of his life, click here. To read a tribute to Mills by poet Jeff Hardin, click here.