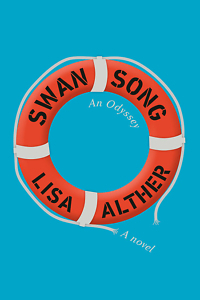

Love and Death at Sea

Lisa Alther’s Swan Song sends its grief-stricken 60-something heroine on a cruise

Forty-five years ago, Tennessee native Lisa Alther published her first novel, Kinflicks — a coming-of-age-in-the-1950s tale that John Leonard, writing in The New York Times in 1976, called “a very funny book, not at all savage, about serious matters, full of people one would like to meet, and oddly invigorating.” It was a bestselling blockbuster. Since then, Alther has written a memoir, a history of the Hatfield-McCoy feud, an account of conversations between herself and the painter (and Picasso’s former mistress) Françoise Gilot, and six more novels.

Her latest, Swan Song: An Odyssey, tells the story of a bereaved woman in her mid-60s who, unmoored by grief, goes to sea in order to gain perspective on her life. It’s a meditation on loss and longing and late-middle age that manages, thanks to Alther’s vivid prose and indomitable protagonist, to be as charming, amusing, and enticing as her debut.

We meet Jessie Drake, an ER doctor in Burlington, Vermont, as she pulls up to the recycling center to dispose of all her sex toys. It’s a fraught, symbolic moment that started as a simple act of housekeeping. The week before, copying names and numbers into a new iPhone, Jessie was taken aback by how many of her contacts are dead. “She pictured herself dead and her son Anthony’s finding her antique VHS tape of Lesbian Hospital while searching for her will. To spare him this trauma, she had decided to dispose of it herself.”

You can’t blame Jessie for viewing life in morbid terms. In the past two years, she’s buried both her parents and her long-term lover Kat, and the strain of so much loss is taking a psychic toll. “She would be minding her own business when, out of the blue, an image of Kat or one of her parents as they lay dying would assail her,” Alther writes. This is certainly understandable, but Jessie refuses to bow to sorrow: “When you started seeing only the sadness of life, with none of the simultaneous beauty and humor, you were in trouble.” It’s time for a change of scene, something to snap Jessie out of a world that feels increasingly tired and sad. When an old boyfriend offers her the chance to come aboard a cruise as the ship’s physician, she jumps at the chance.

And so it’s all aboard the Amphitrite, a fancy British liner named for Poseidon’s wife, goddess and queen of the sea. As the ship makes its way across the Arabian Sea, through the Persian Gulf and Suez Canal to the Mediterranean and finally back to England and New York, a madcap ensemble cast of secondary characters (reminiscent of Agatha Christie in her prime) conspires to snap Jessie out of her funk.

And so it’s all aboard the Amphitrite, a fancy British liner named for Poseidon’s wife, goddess and queen of the sea. As the ship makes its way across the Arabian Sea, through the Persian Gulf and Suez Canal to the Mediterranean and finally back to England and New York, a madcap ensemble cast of secondary characters (reminiscent of Agatha Christie in her prime) conspires to snap Jessie out of her funk.

In her role as ship’s doctor, Jessie’s privy to the most intimate concerns of passengers and crew. Yet she’s also navigating a personal odyssey, and for every moment of high-stakes shipboard drama (Pirates! Refugees! Waves! Sudden death!), there’s a corresponding interval of private reflection, during which our heroine struggles to fathom her grief. “You know,” she tells a fellow crewmember, “I never realized that this trip would become so sinister. When I signed on, I was thinking more along the lines of the Love Boat.” “It’s both, Doctor,” her colleague responds. “Love and death. Eros warring with Thanatos, just like Freud said.”

As the voyage continues, Eros and Thanatos march in lockstep in Jessie’s head. Although she fears she’s grown “too serious for casual sex, and too jaded for serious sex,” opportunities for both hookups and relationships arise. Yet in the end, Jessie chooses to disembark alone, having come to the bittersweet realization that, as the novel’s epigraph states, “The realization of one’s own death is the point at which one becomes adult.”

Sound like a bummer? It’s not. Once again, Alther has written a female coming-of-age tale that’s bound to resonate profoundly with those who are, like Jessie, in their “young old age.” Those who aren’t yet there will relish the novel’s wit, erudition, and charm, which come through on every page. It’s no small thing, at this point in history, to make life aboard a cruise ship seem enticing. Alther pulls it off.

From 2012 to 2016, Fernanda Moore was the fiction critic for Commentary. Her work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Marie Claire, New York, and Southern Living, among others.