Nell Irvin Painter could fairly be called a Renaissance woman. Among her many earned degrees, she holds a Ph.D. in American history from Harvard and an M.F.A. in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design. Now retired from Princeton University, where she was the Edwards Professor of American History, Painter is widely considered one of the most creative and skilled interpreters of the history of the American South and of African Americans. Her books include Creating Black Americans (Oxford University Press, 2006) and Southern History Across the Color Line (University of North Carolina Press, 2002), among many other influential titles.

Painter’s latest book, The History of White People, is a historical synthesis of remarkable scope, ambition, and erudition. Ancient people had no concept of race, and DNA evidence has confirmed that race is entirely a social construct. The History of White People accounts for the development of the idea of a “white race,” from antiquity to the modern age, considering varying degrees and kinds of whiteness over time, and Painter highlights a dizzying array of historical figures and their ideas, some largely forgotten except by academics, others more prominent and well known. All of them contributed to the constantly developing idea of the white race and provided powerful organizing principles for American society as those in power sought to police racial boundaries, enforce hierarchies, or satisfy psychological needs for difference from others.

Painter’s latest book, The History of White People, is a historical synthesis of remarkable scope, ambition, and erudition. Ancient people had no concept of race, and DNA evidence has confirmed that race is entirely a social construct. The History of White People accounts for the development of the idea of a “white race,” from antiquity to the modern age, considering varying degrees and kinds of whiteness over time, and Painter highlights a dizzying array of historical figures and their ideas, some largely forgotten except by academics, others more prominent and well known. All of them contributed to the constantly developing idea of the white race and provided powerful organizing principles for American society as those in power sought to police racial boundaries, enforce hierarchies, or satisfy psychological needs for difference from others.

Prior to her upcoming lecture at Rhodes College, Painter answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: You’ve mentioned on a few occasions that you didn’t intend for The History of White People to serve as a corrective to certain histories, that the book instead arose out of questions you had about the origins of the term “Caucasian,” for example. In that context, I’m wondering how you hit on the title of the book. What work is that definite article doing there?

Nell Irvin Painter: You’re right about my shying away from policy recommendations. My book is an intellectual history, a history of a certain kind of science, and it’s written as a history, not as a remedy. It’s not about what white people have thought of or done to non-white people. As I say at the very beginning, it’s about changing constructions of whiteness, from before the idea of race entered Western thought to the present time.

I began with a question stemming from very late twentieth-century news headlines, during a round of the endless conflicts between Russian power and the Caucasus, in this instance, Chechnya. A photograph of bombed-out Grozny was on the front page of The New York Times, making it look like Berlin in 1945. Why, I wondered, are white Americans called Caucasians? I found those answers in eighteenth-century Germany. Then I had to go backwards and forwards in time to get to the ways we think now.

The working title of my book was “Whiteness in Historical Perspective,” which is precise but yet unclear. I’d say that title, and people would look at me, puzzled. I’d say, you know, the history of white people. Then there was the matter of the article: should it be “a” or “the.” I chose “the” as a power move. To call it A History of White People would be kind of wimpy. I’m too much of a feminist for that.

The working title of my book was “Whiteness in Historical Perspective,” which is precise but yet unclear. I’d say that title, and people would look at me, puzzled. I’d say, you know, the history of white people. Then there was the matter of the article: should it be “a” or “the.” I chose “the” as a power move. To call it A History of White People would be kind of wimpy. I’m too much of a feminist for that.

Chapter 16: The troubling relationship between ideas of race and beauty is a central theme of the book. While critiquing some questionable race-based notions of beauty, you also make a few of your own aesthetic judgments about the beauty of certain people, and with deliciously ironic wit. Would you say that evaluating the “beauty” of others, even while notions of beauty are always in flux, is an inescapable human impulse?

Painter: I have a book to write on beauty, so I can talk about it forever. But not here, not now. We love to talk about beauty because it has a biological hook: sex appeal. At its most fundamental, beauty is about sex. It’s about reproduction, one of the most powerful human drives, right up there with eating. The bedrock of beauty is what to people looks like—underline looks like—reproductive promise, i.e., youth and health.

After youth and health, beauty is all about culture. Some cultures like sex partners to be skinny; some like fat. Some like scarification and tattooing; others like smooth blankness. Many techniques people use to make themselves beautiful (in a cultural sense) actually harm reproduction, such as white lead, which can cause cancer, to whiten faces that are already light skinned.

So, yes, evaluating beauty, in the sense of choosing sex partners, is a basic human impulse. Beyond that, human cultures have erected entire industries on altering how people look. Americans, North and South, spend billions on cosmetic surgery, weight-loss remedies, fashion, and beauty pageants, just to name four huge beauty industries.

Chapter 16: I really enjoyed your sketches of the monstrous people described by Pliny the Elder. To what extent did your deeper interest in visual art influence your historical writing in a book like this?

Painter: Thanks, I’m glad you liked my drawings. Visual art, which is the field dedicated to making things to look at, is absolutely fundamental to The History of White People. You mentioned the theme of beauty in science, which no other scholar of race has examined at length. That, I’m sure, is because no other race scholar has been in art school during the writing of her book.

Painter: Thanks, I’m glad you liked my drawings. Visual art, which is the field dedicated to making things to look at, is absolutely fundamental to The History of White People. You mentioned the theme of beauty in science, which no other scholar of race has examined at length. That, I’m sure, is because no other race scholar has been in art school during the writing of her book.

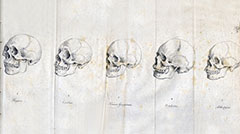

In my lecture at Rhodes I’ll talk about how making the illustrations concentrated my thinking on the individuality of the five skulls that Blumenbach used to exemplify his five varieties of mankind. I had known about that and mentioned it in the writing of my book. But making art for the lecture focused my attention on the skulls as having belonged to particular people, three of whom were young women linked to science through sex. The woman whose skull became the emblem of human beauty and that made white people “Caucasians” had been a sex slave from Georgia (in the Caucasus) who was raped to death in Moscow.

Visual art is partly about making art, but it’s also about concentrated looking. As an artist, that’s what I do. So I could see the role of how things looked and of how scholars of how things looked, such as J. J. Winckelmann, influenced thinking about human difference as codified as race.

Chapter 16: The History of White People moves across broad swaths of time but also includes closer examination of certain periods, a narrative strategy which makes the weight of the subject hit home with remarkable force. How did you arrive at this innovative, fugue-like arrangement?

Painter: I’m indebted to other scholars’ work in this regard because I leaned on the scholarship of others, as you can see from the hundred pages of notes at the back and the book’s dedication to the Princeton University Library. I could never have ranged so widely if I had had to do all the research in primary sources or if I had lacked access to so profuse a library. Now, I always checked primary sources, such as Herodotus or Tacitus or Julius Caesar, but I had modern translations with scholarly introductions to guide me.

As for the organization, it’s basically chronological, pausing over pivotal figures like Franz Boas. And the writing technique is my own write-revise, write-revise, write-revise, write-revise, &c.

Chapter 16: Amidst a dizzying array of characters, your treatment of two major figures in particular struck me: Alexis de Tocqueville and Ralph Waldo Emerson, who don’t come off well at all. Given their problems, which you detail in the book, how should readers today think about the work of these two very influential writers?

Chapter 16: Amidst a dizzying array of characters, your treatment of two major figures in particular struck me: Alexis de Tocqueville and Ralph Waldo Emerson, who don’t come off well at all. Given their problems, which you detail in the book, how should readers today think about the work of these two very influential writers?

Painter: I wouldn’t say that Tocqueville and Emerson had “problems.” They were foremost intellectuals of their times. I would hope readers would see them as symptomatic of the cultures they lived and wrote in. If they seem somehow diminished, it’s because we no longer believe the assumptions of their times or because we have inflated their virtues to stretch into all aspects of how we think today. That’s not fair to people of so different a time. After all, they were writing before seismic events in American history: the Civil War, emancipation, and Reconstruction in the nineteenth century and Nazism and the civil-rights revolution of the twentieth century.

Chapter 16: During the 1990s and early 2000s, DNA research soundly discredited race as a biological category even as the social categories for racial self-identification increased. Your book ends on a cautionary note: “The fundamental black/white binary endures even though the category of whiteness—or we might say more precisely the category of nonblackness—effectively expands.” In this context, how do you view the recent rise of the Black Lives Matter movement?

Painter: Yes, at the turn of the twenty-first century, DNA research reminded us that we are so very much the same. And the U.S. census let us designate ourselves in very complex ways. But around 2005 a countervailing urge sought to re-race us, starting with medicine and the reviving of race’s usefulness as a biological category. I see that reaction as a kind of return to the familiar, to familiar social assumptions about difference and the black/white binary. To this day, Americans spend a lot of energy reinscribing racial difference, or, to put it another way, deepening a chasm between races that everyday life is filling up as segregation wears down and we get to know each other better.

Let me sharpen my thought: Americans (of many backgrounds) seek racial difference for psychological comfort. It’s as though knowledge isn’t complete until we know about the race(s) involved. We want the races to differ.

As for Black Lives Matter, I’m so pleased to see this necessary movement arise. Police brutality is an old, old problem, one setting off the urban unrest of the twentieth century in cities like Harlem, Watts, and Newark. Police brutality was the first injustice the Black Panthers addressed in Oakland in the 1960s.

As for Black Lives Matter, I’m so pleased to see this necessary movement arise. Police brutality is an old, old problem, one setting off the urban unrest of the twentieth century in cities like Harlem, Watts, and Newark. Police brutality was the first injustice the Black Panthers addressed in Oakland in the 1960s.

But in terms of the themes in The History of White People, something concomitant has struck me. That is a new consciousness among many white people of white privilege, which only a small minority of anti-racist activists used to be aware of. As a widespread social phenomenon, this is something very new. Very new and promising as a breakthrough in the creation of empathy and perhaps even interracial understanding.

Before this awareness of white privilege among white people, interracial dialogue would often break down as white people, clueless about white privilege, would claim their grandparents came to the U.S., worked hard, and made it on their own, and why can’t black people? This logic ignores the role of suffrage for nineteenth-century Irish men and twentieth-century immigrant men and women, in the context of widespread disfranchisement of black people. Similarly, most white Americans don’t know about the discrimination built into housing, from FHA and Veterans’ Administration loans, and to red-lining.

Those policies benefited people defined as white and crippled people defined as black. You can’t understand where we are today, especially in terms of class, if you ignore the role of white privilege in giving white people a head start and a leg up. If you understand how gender benefits men, you’ve made a start toward understanding how race benefits white people. Only now are large numbers of white Americans able to see these advantages.

[This article originally appeared on February 10, 2015]

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and writes scholarly articles about American political thought and the civil-rights movement.

Tagged: Nonfiction