Not Just Another Word

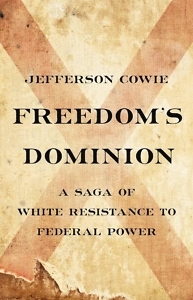

Jefferson Cowie explores the troubling history of racist anti-statism in the South

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: Freedom’s Dominion was recently awarded the 2023 Pulitzer Prize in history. This interview originally appeared on November 17, 2022.

***

Jefferson Cowie, the James G. Stahlman Professor of History at Vanderbilt University, is among the most gifted American historians working in the academy today. He’s the author of The Great Exception: The New Deal and the Limits of American Politics, a broad-stroke reinterpretation of 20th century American politics; the award-winning Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, a vibrant narrative about the decline of class in American political culture; and the transnational history Capital Moves: RCA’s Seventy-Year Quest for Cheap Labor, which charts the relocation of one firm through four cities, two countries, and a great deal of social upheaval.

Cowie’s essays, reviews, and opinion pieces have appeared in The New York Times, American Prospect, Politico, The New Republic, Inside Higher Ed, Dissent, and other popular outlets. His latest book moves south, exploring racialized ideas of freedom in America — exercised most often in white resistance to federal power — through the compelling story of Barbour County in southeastern Alabama.

Cowie recently answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: You insist, to stunning effect, that we take words like “freedom” or “liberty” seriously when white people bent on denying freedom to others use such terms. “Freedom” in this sense isn’t mere rhetorical flourish or “ideological window dressing.” To your mind, why is it essential that we understand these expressions as a species of freedom and not something else?

Jefferson Cowie: Freedom is the most fundamental aspect of the American creed. Yet we often hear “freedom” invoked, not to endorse hopeful ideals, but to justify domination or oppression. When we hear it used to justify unsavory outcomes, we might think, “This is just an appeal to core American ideals to justify whatever the speaker really wants.” But I don’t think that’s right. There’s a dark, troubling aspect of freedom marbled in there with the good.

The Western idea of freedom came from ancient slave societies. To be free was not simply to not be a slave, but also to have the freedom to enslave. Freedom was about power and capacity. If we cast that dark note, the freedom to dominate others, in with a bundle of things we like about freedom — various civil liberties and political freedoms — we end up with a generally positive idea that contains within it some inescapable and problematic elements.

Then, if that more complicated idea of freedom is let loose in a burgeoning slave and settler colonial society, like the American South, we end up with an operative idea of freedom that includes the freedom to steal lands and the freedom to enslave others. It also includes the fight against the federal government that gets in the way of those freedoms. If you consider how freedom is invoked today, it is often in a weird dance with concentrations of power, bigotry, intolerance, land hunger, violence, and a belligerent form of gun rights. Think about how much of our idea of freedom is based on seizing an entire continent.

Philosophers like to create tidy definitions of freedom, but in practice, it ends up being something much more compromised and complex, and to the historian, quite juicy, rich, and telling. Freedom’s Dominion is a long answer to the 18th-century poet and essayist Samuel Johnson. “How is it,” he asks, “that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” The answer rests with the intertwining of freedom and power and the loud demands not to have that freedom constrained.

Chapter 16: You make a strong case for the use of federal (national government) power — however flawed, limited, or compromised. From the 19th century on, federal power has been the critical ingredient in the protection of civic freedoms in this way. What led you to this conclusion, and how does it square with traditions of Black activism in particular?

Cowie: The problem was, and remains, that the same federal power that Black voters believed delivered freedom to them in form of Reconstruction or civil rights legislation, local whites believed to be the long arm of federal tyranny.

Cowie: The problem was, and remains, that the same federal power that Black voters believed delivered freedom to them in form of Reconstruction or civil rights legislation, local whites believed to be the long arm of federal tyranny.

If the brakes are going to be placed on the runaway ideas of white freedom, it’s going to be the federal government that applies them. In fact, this project started by trying to figure out the reasons behind local animosity toward federal authority. When the federal government tries to get white people to stop stealing Native lands, even in a very limited way, or protects Black people’s citizenship rights during Reconstruction, or sends in federal authorities into local counties during the modern civil rights era, these are all seen as infringements on the God-given liberties of white people.

Entire political careers are made by screaming about the disappearance of white freedom at the hands of federal power. Governor George Wallace, who comes from Barbour County, made his local, state, and national career decrying “federal tyranny” and criticizing the Civil Rights Act as the “assassin’s knife in the back of liberty.” A little federal intervention, even when it fails, delivers a whole lot of destructive white freedom in return.

There are a lot of reasons to be deeply skeptical about federal enforcement of civil and voting rights. But, more often than not, the idea of Black activists was to use local struggles to draw in federal authority onto their side. Nearly every dramatic local event in the Black freedom struggle was about trying to federalize the whole idea of citizenship. While I understand the dark side of federal involvement, from mostly criminal negligence to the spying on Martin Luther King Jr., the federal government is the clay-footed hero of my story.

For all of the federal government’s failures, citizenship often turns on the will of federal power. Yet federal power simultaneously generates fears of an imminent loss of freedom. This is what, during Reconstruction, was often expressed as a fear of “Negro domination.” From voting rights to civil rights, Black political freedom depended upon creating a federal idea of citizenship wherever possible. White freedom, in contrast, depends upon keeping citizenship on the local and state levels where it could be controlled.

Chapter 16: We see instances in the book where, on occasion, racist anti-statists gladly use federal policy to pursue local goals when it suits them. Are they just hypocrites, or is there some deeper logic at work in their minds?

Cowie: Most of the history of federal power has been unambiguously on the side of white people. Period. Full stop. But every once in a while, it’s not. And that’s the center of my story. That’s when white people get very agitated about incursions on their freedoms.

In the book, I call the type of local white freedom I am exploring “racialized anti-statism,” but that’s not quite right. Local whites will use whatever political power they can get their hands on, just like everybody else. So if the federal government is helping them and not others, as is the dominate historical trend, everything is fine. The fear in Alabama, however, was always that if the federal government could mess with any one thing, then it could also mess with race relations. So there was always a line that could not be crossed. For instance, white locals across the South were pretty happy about FDR and the New Deal. That worked, at least, until the New Deal began to appear that it might be for someone other than them or when it looked like it could challenge entrenched local and state power relations. Then came the fight.

Champions of white freedom claim that, if you cannot be a master, then you are not free; that if the government is not on your side, then it should not exist. The irony is that many would rather not see the government — even if it is helping them — if it intrudes on the power, both psychological and real, that comes with white freedom.

Chapter 16: Your last couple of books have been rangy syntheses across broad swaths of time. The Great Exception made a case for how Whiggish or liberal versions of American history — the kind that presume some steady progress toward some end — miss a central point about American politics and public policy. This one makes a case for a broad continuity with deep roots in the 19th century, from Indian Removal on up to the post-civil rights era and the present. I wonder whether one can see them as companion pieces. Thoughts?

Cowie: Tough and good question. In my last book, I made the case that the New Deal and postwar eras (roughly 1936-1978) were an “exception” to a long history of political division that punctuated the eras both before and after. The South and race played central roles in that history. For a hot historical minute, the Democratic Party could mobilize both Southern segregationist whites and Black people and still maintain a political coalition with the political bloc known as the Solid South. During this period, federal power was tenuously accepted. While there were concerns that the federal power of the New Deal could upset race relations, it was accepted as largely a boon to white Southerners, not a threat to their freedom.

As soon as the Democratic Party started taking civil rights seriously, however, the coalition crumbled. The Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts began the slow turn of the white South from the Democratic to Republican parties. The rise of Barbour County’s George Wallace to national politics suggests the move from the Democratic past to the Republican future for white Southerners. While having race as a major cleavage point in American politics seemed shocking at the time, as I argue in my last book, this was more of a return to the status quo ante of trying to bury the question of race in America. What we have seen since the 1970s is a slow-moving process, what Reconstruction-era whites called “redemption,” from federal power. Voting rights and civil rights are on the run. But this is not new, it is arcing back to a norm, redeeming white freedom from federal power yet again.

We are still in a long intellectual struggle to decolonize our thinking about everything — including freedom. That upward, hopeful arc you mention has roots in the crumbly, loose soil of a deep, problematic past. This is what The 1619 Project was trying to say. That’s what I am trying to figure out in a different way. And it is scary that we can only take economic justice seriously when race is not allowed to be a factor. FDR was careful to keep race bottled up in the 1930s so that he could pass labor legislation and other forms of economic security in ways that did not happen before and that have not happened since.

Chapter 16: Can you say more about your selection of Barbour County, Alabama, for this story? In your acknowledgments, you mention that “Barbour County found me.” That reads in ways both lyrical and cryptic, something more than accident and less than fate. I’d love to hear more about it.

Cowie: That story begins on a 20 degree-below-zero day in upstate New York. It was so cold I began to fantasize about burning the furniture to stay warm. I was teaching at Cornell University at the time, and my shivering kids came and asked, “Where are we were going for spring break?” “Nowhere,” I replied. Wrong answer.

Next thing I know, we’re all crammed into our little car, motoring down to the Gulf Coast. Once we were off the main freeways, we passed through this little town called Eufaula in the southeastern corner of Alabama to gas up and make the final push to the beach. There were old antebellum-style mansions on stately tree-lined boulevards. I had never seen such an idyllic set piece before.

My historian’s spider senses immediately began to tingle. I knew there was a fascinating story behind the façade. “What is this place?” I asked my wife as we drove through town. She started googling, and said, “I don’t know, but they didn’t have their first integrated high school prom until 1991.”

I’d been thinking about white resistance to federal authority since my New Deal book, and I began to wonder what the best method for getting at that question might be. Since I was well aware of how much you can cherry-pick data on the national level to tell a story, I decided that the challenge of a small rural county in conflict with federal power would be a compelling way to think about the problem. It created research challenges, intellectual constraints, and, I hope, narrative intrigue.

Since some of my previous work was on George Wallace (in my ‘70s book, Stayin’ Alive), most people are going to think I chose this place because of him. But when I got back to the library, I immediately went to the Creek Indian materials, an era I knew little about. I didn’t even figure out that Wallace was from there until much later since I worked through the chronology. When I found him, I knew it was fate.

Fortunately, I then moved to Vanderbilt, and I had great access to the Alabama state archives in Montgomery — a tremendous resource. I should note that I don’t mean to pick on Barbour County, a place I have come to like a great deal. I hope readers will see it as representative of thousands of American places with similar stories to tell. George Wallace certainly understood his home county that way. For him, the stories that connected with voters in this otherwise obscure spot made for a deeply American story, one that would resonate with voters nationwide.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses concerning American culture and thought. He is also a regular blogger for the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH).