Teaching and Unteaching—and Entertaining All the Way

For more than three decades, Patricia McKissack has been writing children’s books that bring to life the stories, and the truth, of her ancestors

As she was coming of age in Nashville in the 1950s, there were many places Patricia McKissack was not allowed to go. She remembers hotels and restaurants that forbade African Americans entry, and movie theaters with a separate doorway in the alley for black patrons. The farthest reaches of the Grand Ole Opry’s balcony, known as the buzzard’s roost, was the only seating open to African Americans, McKissack recalls. She never partook: “My grandfather said that watermelons would bloom in January if any of his children went down there. ‘We don’t sit in no buzzard’s roost,’ he said. ‘We’re human beings, not buzzards.'”

Many years later, McKissack would thread this anecdote into Goin’ Someplace Special, which tells the story of an African American girl of the 1960s who makes her first journey to the downtown library alone, encountering the indignities of segregation along the way. Like many of McKissack’s books, it was based loosely on memories from her girlhood. “The library was the only building you could go in the front door as a black person. The only place,” she recalls. “The librarian treated you with respect. I never knew her name, but I’ll never forget her smiling face. ”

Goin’ Someplace Special is of a piece with McKissack’s contribution to children’s literature—a vast body of work into which she’s channeled her own life stories, those of prominent African American individuals and historical events, and a bounty of folk tales passed down by her elders. Her titles The Dark-Thirty: Southern Tales of the Supernatural; Porch Lies: Tales of Slicksters, Tricksters, and Other Wily Characters; and Mirandy and Brother Wind, among others, provide enlightening entertainment for children, but the books are also repositories for many gems from the African American oral tradition. “It is through me that my family’s storytelling legacy lives on,” McKissack writes in an introduction to Flossie and the Fox, her first picture book.

Goin’ Someplace Special is of a piece with McKissack’s contribution to children’s literature—a vast body of work into which she’s channeled her own life stories, those of prominent African American individuals and historical events, and a bounty of folk tales passed down by her elders. Her titles The Dark-Thirty: Southern Tales of the Supernatural; Porch Lies: Tales of Slicksters, Tricksters, and Other Wily Characters; and Mirandy and Brother Wind, among others, provide enlightening entertainment for children, but the books are also repositories for many gems from the African American oral tradition. “It is through me that my family’s storytelling legacy lives on,” McKissack writes in an introduction to Flossie and the Fox, her first picture book.

In a career spanning more than three decades, McKissack has published titles in just about every subgenre of children’s literature: illustrated books, easy readers, middle grade and young-adult novels, biographies, and many inventive works of nonfiction chronicling African American history and culture, such as 2006’s Stitchin’ & Pullin’: A Gee’s Bend Quilt. (A Booklist reviewer praised the book’s “stirring free verse,” observing that “Both words and images glow with the love, creativity, and strength that are shared among the generations.”) The list of awards and honors McKissack has received for her work nearly rivals her backlist in length, among them Caldecott, Newbery, and Coretta Scott King Honors; the Boston Globe/Horn Book Award; and the Regina Medal from the Catholic Libraries Association.

For much of her work, particularly the nonfiction and including many of the award-winning titles, McKissack has teamed up with her husband Fredrick, who operates as her “leg man” in story research, leaving the writing primarily to his wife. Fredrick is also the handler of her accounts and taxes. (“Twenty-five years, and we haven’t gone to jail yet,” he jokes.) The two have twice won the Coretta Scott King Award—once for the lovely picture book Christmas in the Big House, Christmas in the Quarters, which recounts the holiday rituals of blacks and whites on a real-life Virginia Tidewater plantation; and once for A Long Hard Journey: The Story of the Pullman Porter.

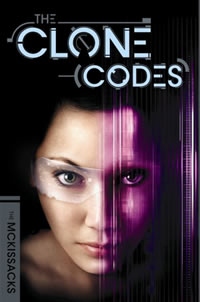

The McKissacks estimate their combined output to tally over a hundred books; they’ve lost track of an exact count. With their most recent release, Clone Codes, the first in a new three-book series for young readers, the couple made their first foray into science fiction, along with a third member of the family, their son John McKissack.

But among Patricia McKissack’s most celebrated books are those that lovingly preserve her family’s storytelling tradition. Her childhood was filled with the voices of her parents and grandparents, who told stories both true and fantastic to listeners of all ages gathered casually on her grandmother Frances’s front porch. It might sound like a Southern cliché—tales handed down casually on long, hot summer evenings, glasses of lemonade at the ready—but such was the authentic heart of McKissack’s upbringing, and hearing those stories told and re-told fostered in her an abiding love of reading and writing. “They made it an art,” she says of her elders’ storytelling prowess.

In McKissack’s folk tales, both narration and dialogue preserve the African American dialect she remembers hearing. “Flossie commenced to skip along, when she come upon a critter she couldn’t recollect ever seeing. He was sittin’ ‘side the road like he was expectin’ somebody,” McKissack writes in Flossie and the Fox, which she adapted from a story her grandfather told. The spirited Flossie refuses to believe, to the fox’s great consternation, that he is what he says he is. “I aine never seen a fox before. So, why should I be scared of you and I don’t even-now know you a real fox for a fact?” she asks. The book charmed readers: “Flossie is a bright-eyed, supremely composed child who works her ruse with quiet aplomb,” wrote a Booklist reviewer. “The story lends itself to reading aloud; the proper dramatic expression will make this a crowd pleaser.”

“I really didn’t have to think a whole lot about [the language],” says McKissack. “I copied Daddy James’ language pattern, but not his language necessarily. It would’ve been too heavy in the dialect, so I had to edit that, make it more readable but yet authentic.”

Anne Schwartz, the editor at Dial Books who acquired Flossie and the Fox and has worked with McKissack on numerous titles since, remembers that when the book was published, in 1986, the time was right for voices of color in children’s literature. “It was a very different world. Publishers saw a market they hadn’t paid attention to before. There was a need for these books, and Pat filled this need.”

The list of awards and honors McKissack has received for her work nearly rivals her backlist in length, among them Caldecott, Newberry, and Coretta Scott King Honors; the Boston Globe/Horn Book Award; and the Regina Medal from the Catholic Libraries Association.

Schwartz also worked with McKissack on Mirandy and Brother Wind, which won a Coretta Scott King Award for its illustrator, Jerry Pinkney, in 1989. Like Flossie, the prose is playful and authentically conversational, a delight to read aloud. Here, McKissack tells a story inspired by Fredrick’s grandparents, Mirandy and Moses McKissack, who won a cakewalk competition several years before they married. (An elementary school and small park are named after Moses, who was a prominent Nashville architect.) Named a Caldecott Honor Book, Mirandy and Brother Wind established McKissack’s reputation in children’s literature and set the stage for much more of her African-African folklore to come.

“Pat has an inimitable voice,” Schwartz adds. “These original folk tales—her voice is stronger there than anywhere else. Nobody else can do what she does with that.”

Born in Smyrna, Tennessee in 1944, McKissack (born Patricia Carwell) moved to St. Louis with her parents, Robert and Erma Carwell, when she was four years old. She spent summers in Nashville with her grandmother until she was twelve, when her parents divorced amicably and Erma Carwell returned to Nashville with Patricia and her siblings. The family settled in the Preston Taylor Homes, a housing development near the Tennessee State University campus. “It was a wonderful, big old neighborhood,” she recalls. “We were called project girls, and there was no shame in it. We could walk home in the dead of night and nobody said a word to us.”

Not far from the Carwells lived McKissack’s maternal grandmother, Frances Oldham, whose white, wood-frame house on Centennial Boulevard resembled a smiling face, McKissack recalls: two windows for eyes, a door for a nose, and the wide and welcoming front porch, which sagged slightly in the middle, forming an upturned mouth. That porch, where McKissack soaked up her parents’ and grandparents’ tales, became the birthplace of sorts for McKissack’s writing career.

Front-porch storytelling time was, traditionally, the thirty minutes or so of twilight, which McKissack and her siblings called “the dark-thirty.” Mama Frances—as McKissack and her friends called her—was especially well known for her skill with ghost stories. Caroline Hardy-Grannum, McKissack’s best friend at that time, lived next door to Frances and remembers those listening sessions: from the “hair-rising tales” like the ones collected in The Dark-Thirty, to Br’er Rabbit stories, to Langston Hughes poems, to a soliloquy by Paul Laurence Dunbar, Erma’s favorite poet. (Later, a biography of Dunbar would be McKissack’s first shot at writing a book.) “You’d just sit and listen whether you were involved or not,” Hardy-Grannum recalls. “Some tales were funny and some were serious, and I think they motivated us to be who we are today. They were an incredible gift to us.” Some stories might subtly pass along a lesson in morals or decorum (ladies, sit with your legs together); others instilled the listener with cultural pride and respect for the past.

Front-porch storytelling time was, traditionally, the thirty minutes or so of twilight, which McKissack and her siblings called “the dark-thirty.” Mama Frances—as McKissack and her friends called her—was especially well known for her skill with ghost stories. Caroline Hardy-Grannum, McKissack’s best friend at that time, lived next door to Frances and remembers those listening sessions: from the “hair-rising tales” like the ones collected in The Dark-Thirty, to Br’er Rabbit stories, to Langston Hughes poems, to a soliloquy by Paul Laurence Dunbar, Erma’s favorite poet. (Later, a biography of Dunbar would be McKissack’s first shot at writing a book.) “You’d just sit and listen whether you were involved or not,” Hardy-Grannum recalls. “Some tales were funny and some were serious, and I think they motivated us to be who we are today. They were an incredible gift to us.” Some stories might subtly pass along a lesson in morals or decorum (ladies, sit with your legs together); others instilled the listener with cultural pride and respect for the past.

McKissack collected a number of the spookier stories from those sessions in The Dark-Thirty, which won the Coretta Scott King prize and was named a Caldecott Honor Book. Publishers Weekly gave the book a starred review, calling it “haunting in both senses of the word.” A reviewer for the School Library Journal wrote, “Strong characterizations are superbly drawn in a few words. The atmosphere of each selection is skillfully developed and sustained to the very end.” While ghosts and other supernatural occurrences are well-represented, the tales also reflect the very real troubles of the legacy of oppression and racism in the American South.

Porch Lies—a delightful (and delightfully illustrated) sort of follow-up to The Dark-Thirty, but with more humor and hi-jinks than goosebumps—seems anchored in real people and places, pages torn from authentic African American culture, with savvy embellishments here and there. “When the teller’s eyes grew mischievously large and bright and his or her hands became as animated as a puppeteer’s, we knew that a porch lie was in the making,” she writes in the introduction to the collection. “I was especially delighted when the story was a slickster-trickster tale about some wily character who used his wits to outsmart his opponents,” McKissack writes. “I like to think of each of these slicksters as a cross between a Mississippi bluesman and Br’er Rabbit, though there were a few women as well. And whether it was someone fast- or slow-talking, a well-dressed city slicker or an innocent-looking country bumpkin, all were gifted with a silver tongue tarnished by an oily reputation. No matter how bad these characters seemed, however, they managed to charm their victims and disarm their critics with just enough humor to take the edge off their unscrupulousness.”

When McKissack and her friends weren’t absorbing the vivid tales of their elders, they led what was by all accounts an exceedingly wholesome, happy teenage existence: they water-skied on Old Hickory Lake, joined the cheerleading squad, and worked as camp counselors. As the civil-rights movement gathered steam, McKissack contributed to the cause by stuffing envelopes, putting up fliers, making telephone calls, and attending a few marches. But her mother strictly forbade her to attend the sit-ins happening downtown, just a few miles from their home. “My uncle was on the police force, and he was worried about me,” says McKissack. “He said he knew guys who were beating kids up; he knew they were doing it, but he couldn’t stop them.” Fred McKissack, on the other hand, who was several years older, did participate in a sit-in at Woolworth’s in downtown Nashville. “He was one of the first, and a woman had a shotgun leveled at his head. Think about that,” she says.

“The past has been so terribly misrepresented in a lot of our textbooks. Misinformation means you have to unteach things, and unteaching is far more difficult than teaching. It took a lot of unteaching to get me to where I have a clear understanding of what happened to my ancestors. Even today, with a black president, we’re still feeling the ugliness of racism.”

McKissack brought that tumultuous era to life for a new generation of young readers in 2006 with Abby Takes a Stand, the first in a clever five-book series called “Scraps of Time,” which introduces children to significant periods in twentieth-century African American history through the adventures of engaging young characters from several generations of one Nashville family. In Abby Takes a Stand, set in 1960, a little girl is castigated for entering a whites-only restaurant called the Monkey Bar (a real Nashville landmark, it was a restaurant located inside the Harvey’s department store at 6th Avenue North and Church Street, one site of the sit-ins in 1960). Abby gets involved with the burgeoning civil-rights movement, helping out in much the same ways McKissack did back then. (In other books in the series, the characters study writing with Zora Neale Hurston in the Harlem Renaissance and play ball with members of the Negro Baseball League; McKissack is working on the fifth and final title, whose narrative will focus on the race riots that broke out surrounding the integration of the Nashville public schools in the late 1950s.) “Abby is an engaging character whose sharp observations provide emotional connections and a sense of time and place,” a Kirkus reviewer wrote. “By personalizing events, historical fiction can bring the past alive for children, whose concept of time is unformed. McKissack succeeds admirably.”

McKissack graduated from Pearl High School and Tennessee State University, where she earned a degree in English. Soon after that, she married fellow TSU grad Fredrick, a former U.S. Marine and civil engineer, who proposed on the couple’s second date. In 1965, the McKissacks moved to St. Louis, where Fredrick had a job with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and where they’ve lived since. They have three grown sons: twins Robert and John, and Fredrick Jr.

In the early years of marriage and motherhood, McKissack stoked her interest in literature with regular trips to the library with her sons, and by joining writers’ organizations and attending conferences. She wrote, sent work out, collected rejections, sent work out again—the usual pattern. After teaching eighth-grade English for nine years, she went to work at Concordia Publishing House, an arm of the Lutheran Church of Missouri, where she worked as an editor of children’s books. “It taught me a lot about my own writing,” she says. After six years, she decided to leave Concordia to pursue her own books. Frederick not only supported her dream but agreed to join forces with his wife to realize it.

“Writing books for children wasn’t something I’d ever thought about doing,” Fredrick says, “but I have enjoyed it. We were in a time of great change for African Americans [when we started], and it was interesting to hear and read stories of black Americans. I didn’t know a think about Tuskegee. It was nice to go there and see where Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver worked. I thought I’d go back to engineering eventually, and she’d go back to Concordia. But every time we got ready to quit, something good would happen. People would ask us to do [books], and we’d do them.”

“Pat was one of those trailblazers who was getting books out there for kids who weren’t used to seeing themselves in books,” says Jennifer Arena, the Random House editor of Stitchin’ & Pullin’. “Each book that she does adds to that story.” Arena notes that McKissack is as fluent in the voices of contemporary lit as she is those of historical nonfiction and folk tales—a skill that’s evident in the fresh, realistic voices of the characters in her “Miami” series of chapter books for young readers. Miami, a headstrong, talkative boy, is an amalgam of McKissack’s three sons, developed in response to their desire for more books with black characters who were like them.

“The past has been so terribly misrepresented in a lot of our textbooks,” McKissack says. “Misinformation means you have to unteach things, and unteaching is far more difficult than teaching. It took a lot of unteaching to get me to where I have a clear understanding of what happened to my ancestors. Even today, with a black president, we’re still feeling the ugliness of racism. Obama’s election has brought out some ugliness that I didn’t think still existed, could exist. It’s amazing some of the things you hear. But I’m amazed at where we are, and I’m glad I’ve made the contribution that I have.”

McKissack’s four grandsons (and one grand-niece who knows her as Aunt Grand) do know a world that’s very different from the one their grandmother experienced growing up. And the Nashville McKissack knew as a girl no longer exists, in both small and large terms. Mama Frances’s smiling house on Centennial Boulevard was torn down years ago. The Preston Taylor Homes are gone, too, replaced by new subsidized housing in what’s now a neighborhood called Tomorrow’s Hope. Erma Carwell passed away five years ago. The Nashville that was—and the stories that came to life on Mama Frances’s porch on Centennial Boulevard—live on in McKissack’s books—those already published, and the ones yet to come.

“I am the oldest member of my family still alive,” she says. “I’m the matriarch. And it’s my time to make sure the grandchildren know the stories—and that they know who they belong to. And that they continue to hold on to certain family-oriented values. The values that have held us together for generations.”

[This article originally appeared on 3/10/2010.]