While she was still in college, Jena Lee Nardella felt drawn to serve people who are overlooked. That calling led to a meeting with Jars of Clay, a Nashville-based Christian rock band with a dream of mobilizing Americans to advocate for AIDS clinics and clean-water wells in African communities. “We know that Christ gave himself fully as both blood and water poured from his side as he died on the cross,” Dan Halstine, the band’s lead singer, said to Nardella in their first meeting. “We know that the people of Africa are in peril over those two life-giving substances: clean blood, blood free of HIV. Clean water.”

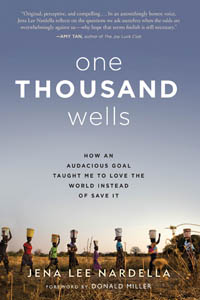

Nardella took his words to heart: “What part of blood and water will I be for the people of Africa?” she asked herself. With no guarantee of a salary or even a place to live, she left her home in Washington state and headed to Nashville to help the band found a nonprofit called Blood:Water. In her new memoir, One Thousand Wells: How an Audacious Goal Taught Me to Love the World Instead of Save It, Nardella writes of their combined efforts to turn what was “only a dream and a P.O. box” into an enormously successful force for good in HIV-affected communities, bringing clean blood and clean water to more than 62,000 Africans in eleven countries.

Nardella took his words to heart: “What part of blood and water will I be for the people of Africa?” she asked herself. With no guarantee of a salary or even a place to live, she left her home in Washington state and headed to Nashville to help the band found a nonprofit called Blood:Water. In her new memoir, One Thousand Wells: How an Audacious Goal Taught Me to Love the World Instead of Save It, Nardella writes of their combined efforts to turn what was “only a dream and a P.O. box” into an enormously successful force for good in HIV-affected communities, bringing clean blood and clean water to more than 62,000 Africans in eleven countries.

From the inception of Blood:Water, the group’s vision was to build a thousand wells in Africa through community empowerment and participation. In Africa, understanding that people don’t respond to needs as readily as they do to opportunities, she and the band members worked to facilitate lasting change at a grassroots level by prioritizing individual dignity, integrity, responsibility, and human relationships.

With the knowledge that it takes only one dollar to provide a year of clean drinking water for a person living in Africa, the band set out on tour in 2004 with the goal of inspiring every audience member to donate a dollar to Blood:Water. From her sometimes tense time with them on the tour, Nardella came away with an understanding that trying to make an impact with your life is risky. “Missional vocation will break you, taunt you, do whatever it can to test whether you mean it when you say you want to serve the poor,” she writes. “We would need grace to carry us through.”

The same year, as a trickle of donations became a steady stream, she took her first official Blood:Water trip to Kenya. This trip was eye-opening on multiple levels, primarily because of her interactions with people, but also because of the insight it brought into her own desire for adventure. Nardella acknowledges that she wanted to experience the vast landscapes, exotic animals, and village life in Africa almost as much as she “wanted to help the people living there.” With the clarity of recognizing that working in developing countries is never purely altruistic, she also came to understand “the joy that comes, even at the intersection of need and pain, when we are where God wants us to be.”

The same year, as a trickle of donations became a steady stream, she took her first official Blood:Water trip to Kenya. This trip was eye-opening on multiple levels, primarily because of her interactions with people, but also because of the insight it brought into her own desire for adventure. Nardella acknowledges that she wanted to experience the vast landscapes, exotic animals, and village life in Africa almost as much as she “wanted to help the people living there.” With the clarity of recognizing that working in developing countries is never purely altruistic, she also came to understand “the joy that comes, even at the intersection of need and pain, when we are where God wants us to be.”

Nardella’s steadfast honesty, humility, and the strength of her calling make One Thousand Wells deeply compelling reading. Hers is a story of a humanitarian work done by people who see that in order to understand the suffering of others they must risk being fully human. “I took courage,” she writes, “in knowing Jesus could relate to each person’s burdens and hopes, even if I could not.”

During many more trips to Africa, Nardella forged connections with people of all ages, many of them barely surviving. She shares details of their humanity, of their astonishing hope and generosity in the most uninhabitable circumstances. On one trip to northern Uganda, for instance, she visited a displacement camp of 1,300 people, all relying on a water source with a broken pump. In covering the cost of its repair, Blood:Water didn’t adhere to its stated ideal of long-term development, but Nardella recognized something equally important: there are times when best practices are less important than mercy.

Sarah Norris holds an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction from Sarah Lawrence College and has reviewed books for The Daily Beast, Christian Science Monitor, San Francisco Chronicle, and Village Voice, among other publications. She lives in Nashville.

Tagged: Nonfiction