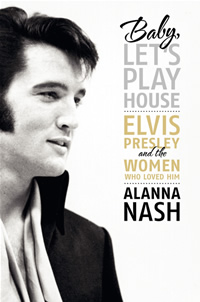

All The King's Women

Journalist Alanna Nash plays sex therapist in this often-disturbing look at Elvis’s most intimate relationships

He had everything—talent, adoring fans, firearms, cash, cars and mansions—but most importantly, he had women. Lots of women. In Baby, Let’s Play House, music journalist Alanna Nash uses Elvis’s Bacchanalian appetites as the starting point for an exhaustive look his psychology. Though not always clinically successful, Nash’s portrayal of the King as a doomed sexual superboy is an enthralling, if guilty, pleasure.

Elvis Aaron Presley was born in impoverished East Tupelo, Mississippi, during the early morning hours of January 8, 1935. His twin, Jessie Garon, was stillborn, a tragedy that would haunt Elvis the rest of his days. In Baby, Let’s Play House, Nash relies heavily on the work of psychologist and Elvis biographer Peter O. Whitmer (The Inner Elvis, 1996). As a “twinless twin,” Nash and Whitmer claim, Elvis was “forever trapped in an endless loop of dissatisfaction and suffering.”

According to their assessment, Elvis was a victim of prolonged grief disorder, an affliction that creates a compulsive need for human contact. Add to that obsession an unnatural attachment to his mother, Gladys, who died in 1958 when Elvis was at the peak of his powers, and you have a man who, despite being irresistible to most women, was utterly unable to engage in a healthy sexual relationship.

According to their assessment, Elvis was a victim of prolonged grief disorder, an affliction that creates a compulsive need for human contact. Add to that obsession an unnatural attachment to his mother, Gladys, who died in 1958 when Elvis was at the peak of his powers, and you have a man who, despite being irresistible to most women, was utterly unable to engage in a healthy sexual relationship.

It’s this reality-show version of dysfunction that gives Baby, Let’s Play House its prurient appeal. Using primary and secondary sources, Nash provides an oral history of sorts that depicts Elvis as an insatiable sex addict with an almost mystical power over women. For example, from Viva Las Vegas co-star Ann-Margaret, with whom Presley had a long and passionate affair, we learn that the pair were caught up in “a force we couldn’t control. … It was a strong relationship, very intense.” And from executive producer Steve Binder comes the legend that Elvis experienced a “sexual emission on stage” during the recording of his 1968 legendary “Comeback Special.” If true, such a feat may solidify Elvis’s reputation as the greatest sex symbol ever, but it is also, in Binder’s words, “not a normal act.”

According to Nash, Elvis involved himself with a constantly revolving cast of women in a vain attempt to make himself feel whole. There were sex kittens like Ann-Margaret, Juliet Prowse (a dancer Elvis was seeing behind Frank Sinatra’s back), and Natalie Wood, as well as “nice girls” with whom Elvis would only have chaste sex: light petting and pajama games. Elvis’s “elegant pajamas never came off, but it didn’t matter,” Nash writes. “He and Judy [Geller] spent the whole night hugging and kissing, doing everything and nothing.”

According to Nash, Elvis involved himself with a constantly revolving cast of women in a vain attempt to make himself feel whole. There were sex kittens like Ann-Margaret, Juliet Prowse (a dancer Elvis was seeing behind Frank Sinatra’s back), and Natalie Wood, as well as “nice girls” with whom Elvis would only have chaste sex: light petting and pajama games. Elvis’s “elegant pajamas never came off, but it didn’t matter,” Nash writes. “He and Judy [Geller] spent the whole night hugging and kissing, doing everything and nothing.”

Many of Elvis’s conquests were underage, most significantly his child bride Priscilla Beaulieu, who was fourteen when they met. Nash turns to psychologist Whitmer to explain the attraction. In Priscilla “he found himself a little Elvis-like sylph, and he became the owner of it, the control of it, the mother, the father, the Holy Ghost. Everything.” More succinct is a quote from Francis Forbes, a young girl whom Elvis saw frequently during the late 50s: “Fourteen was a magical age for Elvis. It really was.”

At times, Nash comes off as a bit of an armchair psychologist. Her claim that Elvis and Gladys’s “covert incest contributed to a sense of shame, sexual confusion and conflict,” for example, makes for tidy storytelling but is all but impossible to prove. Neverthless, Baby, Let’s Play House has an overarching moral that Nash hardly needs mention: this is the story of a man who possessed everything our popular culture deems worthy—money, sexual attractiveness, and fame—but was still miserable. What better way to the heart of such a tale than through the words of the women who knew him best?

Alanna Nash will read from and sign copies of Baby, Let’s Play House at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis in January 7 at 6 p.m.