Landscapes of Her Heart

Elizabeth Spencer, one of the South’s greatest writers, discusses her work, her years in Tennessee, and her friendship with Eudora Welty

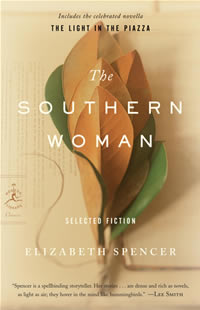

It’s hard to know where to begin to catalogue the literary achievements of Elizabeth Spencer. In a career than spans more than sixty years, the Mississippi native has published nine novels, seven story collections, a memoir, and a play. Her work has garnered critical acclaim and a passel of honors and awards, including the prestigious PEN/Malamud award in 2007. At age 88, she still pursues the art to which she has contributed so much. One of her stories is included in the 2010 edition of New Stories from the South, Algonquin’s yearly anthology of notable short fiction by Southern authors.

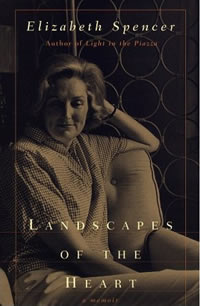

Spencer’s personal and literary roots are as deeply Southern as they could be. She was born and raised in Carrollton, Mississippi. As an undergraduate at Belhaven College in Jackson she developed an enduring friendship with Eudora Welty. In 1942, Spencer began graduate work at Vanderbilt, where she was a student of Fugitive poet Donald Davidson and came to know Allen Tate. Her graceful memoir, Landscapes of the Heart, contains a lively account of her Nashville years, which included a stint as a reporter for the Tennessean and a teaching job at Ward-Belmont College, a school for women on the site of the current Belmont University.

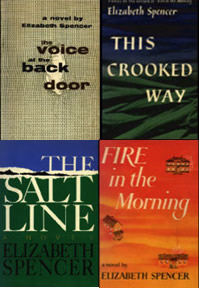

Much of Spencer’s work is set in the South, including The Voice at the Back Door, a widely praised 1956 novel about racial tensions in small-town Mississippi. But despite her reputation as a Southern writer, Spencer actually spent much of her adult life outside the United States, living for many years in Italy and Canada, countries that have also served as locales for her fiction. Florence provides the setting for her most famous work, The Light in the Piazza, a poignant tale about an American woman who finds unforeseen possibilities for her handicapped daughter in the exotic atmosphere of Italy. First appearing as a story in The New Yorker, The Light in the Piazza was later published as a novella and became a finalist for the National Book Award in 1961. (Other finalists that year included Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and John Updike’s Rabbit, Run.) Olivia de Havilland starred in a Hollywood adaptation of the story, and a 2005 musical version won six Tony awards.

Much of Spencer’s work is set in the South, including The Voice at the Back Door, a widely praised 1956 novel about racial tensions in small-town Mississippi. But despite her reputation as a Southern writer, Spencer actually spent much of her adult life outside the United States, living for many years in Italy and Canada, countries that have also served as locales for her fiction. Florence provides the setting for her most famous work, The Light in the Piazza, a poignant tale about an American woman who finds unforeseen possibilities for her handicapped daughter in the exotic atmosphere of Italy. First appearing as a story in The New Yorker, The Light in the Piazza was later published as a novella and became a finalist for the National Book Award in 1961. (Other finalists that year included Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and John Updike’s Rabbit, Run.) Olivia de Havilland starred in a Hollywood adaptation of the story, and a 2005 musical version won six Tony awards.

In 1986, Spencer accepted a teaching appointment at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where she still lives. A documentary on her life and work, Landscapes of the Heart: The Elizabeth Spencer Story, directed by Kevin McCarthy, will appear later this year. Spencer will give a public reading at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference on July 14 at 4:15 p.m. She spoke with Chapter 16 by phone from her home in Chapel Hill.

Chapter 16: You’re often called a master of the short story, and I wonder if you feel that mastery when you write. Do you approach the blank page in a different way now than when you started?

Spencer: Oh, I must, I guess. I realize it’s always hard. You’re talking about me as a short-story writer, though I started out as a novelist, and my last novel was published in, I think, ’91. So I continue to think of myself as a novelist; it’s just that my short stories seem to have hit more people as my most successful form. But I’ve written nine novels, after all. I wish people would pay attention to those. Anyway, I’m grateful for any attention.

Chapter 16: You mention on your website that you have a novel in progress.

Spencer: I’ve been trying to finish this novel for years. I may just finally give it up. I think of starting others and trying to finish them, too. I like the short novel form very much. The Light in the Piazza was a short novel. It was [first] published as a long story in The New Yorker, and [then] published separately. I don’t know much difference between a long story and a novella, but it was meant to be a novella. That’ s a very good form, I think, because it’s in between the two forms. Some awfully good things have been written that way.

Chapter 16: Do you think there’s a market issue for novellas?

Spencer: A market issue—well, I don’t know. You’ve got to find a place to publish them. I published a book called Jack of Diamonds. It’s out of print now, but the stories are all in print, and I looked at that collection of five stories as being more novella length, and the feeling of them was more novella than story. Story is strongly concentrated, and in a novella you can kind of stretch out a bit and bring in a lot of side issues. It makes for more richness in the form.

Spencer: A market issue—well, I don’t know. You’ve got to find a place to publish them. I published a book called Jack of Diamonds. It’s out of print now, but the stories are all in print, and I looked at that collection of five stories as being more novella length, and the feeling of them was more novella than story. Story is strongly concentrated, and in a novella you can kind of stretch out a bit and bring in a lot of side issues. It makes for more richness in the form.

I was trying to finish this [new novel], but it’s like a little nightmare, I can’t ever finish it. I’ve been doing some other stories recently.

Chapter 16: You certainly seem to be very prolific still. Do you ever think about putting the work aside and saying, “I think I’m done?”

Spencer: Well, it’s an old habit. It’s sort of like biting your nails. How do you quit? But no, I feel that I’m not quite all there unless I’m working on something. Most of the work goes on in my head. I don’t write nearly as much as I used to. It’s true that when I turn out a story and feel that I’ve done something good, somebody will usually publish it and then it will drift into anthologies and stuff like that.

Chapter 16: I saw that you had a play, For Lease or Sale, that was produced in Chapel Hill.

Spencer: I did, but it never went anywhere else. People liked it. It was put under contract once, but they didn’t produce it. Theater isn’t my form, but there was a very energetic young man here who was head of the playmakers at the University of North Carolina who wanted to produce it, and he did. We had some success on it. I think it was even held over, but as far as that goes it never went on to be produced anywhere else. So I guess I wasn’t really the person to do a play.

Chapter 16: Was it published?

Spencer: It’s published in a collection of Mississippi [writers]. Mississippi, where I’m from, did a large collection of short stories, poetry, essays and drama, and it was put in the one on drama, but that’s the only place it was published, and that book wouldn’t be anywhere but in libraries. I don’t know—I’ve come to think maybe it wasn’t very good after all. If it were, somebody would have picked it up by now.

Chapter 16: Getting back to your novels, you’ve said you felt The Salt Line was one of your most successful novels.

Spencer: I do feel that. It sold pretty well. It was in the Penguin Series of Contemporary Literature and it’s still in print. That’s pleasing for me. It was laid on the Gulf coast as a result of Hurricane Camille, but, my lord, the Gulf coast has been through such a beating after that, probably it doesn’t seem that that was so remarkable. After that they had Katrina and now they’ve got this stupid oil spill. [The novel] doesn’t address itself just to the aftermath of a hurricane. It’s about people after a disaster trying to rebuild their lives, and disasters have affected, in the past, all the major characters. I think it’s a good story and I enjoyed doing it. I thought it was fairly successful.

Spencer: I do feel that. It sold pretty well. It was in the Penguin Series of Contemporary Literature and it’s still in print. That’s pleasing for me. It was laid on the Gulf coast as a result of Hurricane Camille, but, my lord, the Gulf coast has been through such a beating after that, probably it doesn’t seem that that was so remarkable. After that they had Katrina and now they’ve got this stupid oil spill. [The novel] doesn’t address itself just to the aftermath of a hurricane. It’s about people after a disaster trying to rebuild their lives, and disasters have affected, in the past, all the major characters. I think it’s a good story and I enjoyed doing it. I thought it was fairly successful.

Chapter 16: I thought maybe by “successful” you meant artistically successful.

Spencer: Oh, I did. That’s what I meant.

Chapter 16: I wonder exactly what that means to you as a writer. Why do you feel that something’s successful or not?

Spencer: Well, it’s that I enjoyed doing it and feel that I’m really gaining a hold on things in general when I’m doing it. Then when I finish it I think, well, I didn’t do badly with that. I feel a sense of accomplishment about it. I suppose all my novels at one time or another I felt that way about, or I wouldn’t have done them. But that one sort of lingers in my mind. Mainly, I guess, it’s because I always loved the Gulf coast. I was brought up in Mississippi, but going down there and being there as many times as I have, I have real affection for it, and I’m sorry to think it’s lost forever.

Chapter 16: Do you feel that connection with Tennessee at all?

Spencer: I worked on the Tennesseean for a year. I went to school at Vanderbilt. I just feel that Nashville is one of my basic places.

Chapter 16: In your memoir you give a wonderful description of Nashville during the years you lived there.

Spencer: I enjoyed doing that. They’re doing a voice recording of me reading Landscapes of the Heart, and I just read that [section] aloud the other day for the recording.

Chapter 16: Is the recording part of the documentary that’s being made?

Spencer: It’s being done by the same people, and it will probably be partly included in the documentary, but they want to market it separately.

Spencer: It’s being done by the same people, and it will probably be partly included in the documentary, but they want to market it separately.

Chapter 16: Is the documentary supposed to come out this year?

Spencer: I think they’re planning to be through [with it] this summer. They ran into a bit of trouble because just after they started it and had all their plans laid, the financial crisis hit, so they had troubled materializing some of the money they had planned to get. But I think they’re going to finish it this summer.

Chapter 16: And the documentary is just about the arc of your life and your career?

Spencer: That’s right. The man they have doing it is a filmmaker, and he’s knows what he’s doing, I hope. Giving your whole life over to somebody to make a film of it is a little but chancy. It’s hard to know what they’ll do, but I’m sure since he’s involved so much of his time and energy to it, it couldn’t fail to be complimentary of my work. But, on the other hand, I don’t know what angles he’s going to explore. He’s been to Mississippi two or three times. He loves Mississippi. He’s of French and English extraction, mainly English, and he said he’d never seen a place like Mississippi in his life.

Chapter 16: Talking about Mississippi brings me to the whole regional-writer issue. You’re pegged as a Southern writer, although much of your work is set outside the South and you’ve lived outside the South for years. Do you ever resent that label?

Spencer: I don’t mind being called a Southern writer. People have to catalog you in some way so that they can approach you from that angle. What else could they call me? I lived in Canada for a good while. My husband [John Rusher, who died in 1998] was working there, and I’m still in Canadian Who’s Who, so it must mean that I’m somehow associated with Canada. One book I wrote, The Night Travellers, was gleaned very peripherally from the experiences I knew about of a lot of people who came up to Canada during the Vietnam War. There were a good many people who didn’t believe in that war and came to make a life for themselves in Canada. And I somehow, though accident or acquaintances of some kind or other, got to know a lot about those people.

Chapter 16: That’s the most recent novel you did, isn’t it?

Spencer: I haven’t done a novel since, except that one I keep gnawing at now.

Chapter 16: There’s a debate now about whether there are going to be genuinely Southern writers coming up. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Spencer: There seem to be a whole lot of people around in North Carolina—Chapel Hill especially—that are writing books that are based in Southern scenes and people. It’s been said that Southern literature breeds Southern writers, rather than the locale. I don’t know if it’s true; I would like not to think so. But there are some good writers around that certainly are Southern-based in their writing. Lee Smith—her last novel surprised everyone. It was historical, and I hadn’t known her to write historical fiction before, but she got a good theme going. That was a good novel. I liked it. Jill McCorkle, who’s coming up to Sewanee, has written a number of books and stories laid in the South. So I suppose as long as the South geographically is there, people who live in it are going to write what they call Southern fiction. How do you define Southern fiction? It seems to me it’s fiction laid in the South.

Spencer: There seem to be a whole lot of people around in North Carolina—Chapel Hill especially—that are writing books that are based in Southern scenes and people. It’s been said that Southern literature breeds Southern writers, rather than the locale. I don’t know if it’s true; I would like not to think so. But there are some good writers around that certainly are Southern-based in their writing. Lee Smith—her last novel surprised everyone. It was historical, and I hadn’t known her to write historical fiction before, but she got a good theme going. That was a good novel. I liked it. Jill McCorkle, who’s coming up to Sewanee, has written a number of books and stories laid in the South. So I suppose as long as the South geographically is there, people who live in it are going to write what they call Southern fiction. How do you define Southern fiction? It seems to me it’s fiction laid in the South.

Chapter 16: So it’s about the place and not about the culture? Southern culture has certainly changed a lot. You can argue about whether it has disappeared, but it has changed profoundly.

Spencer: As long as people live here in the South, I suppose they’re Southerners, and as long as they write about people living in the South, I suppose that’s Southern fiction. Are you thinking that Southern culture the way it used to be is what makes Southern fiction?

Chapter 16: That seems to be the debate. The central concerns of Southerners—like race, for example—have changed. The South is not peculiar in its racial problems anymore. It has the same racial issues as the rest of the country, basically.

Spencer: But still, we have a history that’s different, I think, racially, from the rest of the country. A lot of the Southern historical themes have persisted a long time, and that was what Lee Smith was going back to in her novel. It wasn’t particularly about race, at all. It doesn’t have to be about race.

Chapter 16: No, not at all. It was about a young woman, and that brings me to my next question. Your women characters are so memorable. How do you feel about feminist interpretations of your work?

Spencer: I don’t know what it is. What do you mean by feminist interpretation?

Chapter 16: I’m thinking about the Marilee stories and The Light in the Piazza—these women who are very quietly at odds with their environment and they take a leap of faith of some kind.

Spencer: I guess so. I don’t know what leap of faith Marilee took, but she was amusing to write about. I enjoyed doing that. Oh, you’re talking about the woman in The Light in the Piazza. Well, she was in a special set of circumstances, and then she kind of discovered she had a certain rebellious side to her that she didn’t really know she had. When her deep emotions were involved she made a leap, but she was in a foreign country. I doubt if she would have dared do any of that if she had been in her own country.

Chapter 16: Do you see a particular set of issues for those women characters separate from the men, just because they’re women, or are their dilemmas just the same?

Spencer: You have to take each story at a time to question that. Each one is different, isn’t it? I like to dwell on characters who embody a lot of possibilities that might lead them to decisions that will be changing in their lives. I suppose something like that is at work in what I write. People are always opening new doors and finding new thresholds. But you have to tell me a specific work you’re referring to, because the trouble with me is I can’t generalize very well about things. Just because I write about one woman who behaved unexpectedly in Italy doesn’t mean—you’d have to ask me which story, because I don’t know how to generalize about it.

Chapter 16: So you approach your characters very personally, very much as individuals.

Spencer: Oh, yes. [With] each one I try to follow out what I think they would feel or do, and identify as much as I can.

Chapter 16: You have several characters who recur, like Edward Glenn.

Spencer: Now that’s interesting because I’ve written a number of stories about that guy. The play I wrote was about him. He just keeps cropping up different places that I suddenly am stirred to imagine, or realize that there he is again. So I’ve written four or five stories, it’s true, about him in addition to the play, and I may try to make a whole work of it someday. He’s one of those characters like Marilee who doesn’t let you alone. He shows up all the time in different connections.

I don’t know of any other characters that I’ve followed in different works. Those two are the only ones.

Chapter 16: Is Edward Glenn in the novel you’re working on?

Spencer: No, he’s not.

Chapter 16: In your memoir you mention many writers you have known over the years, but you seem to have had a particular relationship with Eudora Welty.

Spencer: When I was in Belhaven College—it was a little girls’ school when I went to it. I think it’s a university now and it’s coed—but it was a Presbyterian girls’ school, very pretty campus and everything. Pinehurst Street was one of the four streets that bordered it, and right there on Pinehurst Street was Eudora Welty. When I was in school she had just published her first book, and some of us wanted to ask her over to meet with our little writing group. We had a little group of us that wanted to be writers who got together. And she came, and I think we got to be friends that first evening.

She got talking to me because she liked what I wrote, and was very forthcoming in all the things she envisioned that I could [do], people I should know, and all that. People said that she was my mentor. She never mentored me at all about anything. In fact, we didn’t talk about writing a great deal, but she was always a good friend and very supportive of my work once it got out, and I always appreciated that so much. That friendship lasted through all the years and that was a very big boost for me, as it would be to anybody just knowing Eudora, no matter what they did. That was a very happy relationship.

Chapter 16: Leaving aside the issue of mentoring, do you think it’s encouraging for a young writer to know other writers? Does that help you keep faith in what you’re doing?

Spencer: It is, it is. Some of it might be a put down rather than an advantage, but all the writers that I got to know when I was younger were wonderfully helpful and supportive. I think of a few who weren’t but I wouldn’t like to go into that. On the other hand, most of them [were.] There was a strong group of Southern critics, poets, fiction writers then that was not ever to be repeated, I think, because they were dominant everywhere in American literature, and I think I’ve written about that, too.

Chapter 16: In your memoir you write that there was a certain conventional wisdom that you were supposed to subscribe to, about who was worth reading and who wasn’t.

Spencer: Oh, yeah, well that spread at Vanderbilt, but the source of that, oddly enough, seems to have been T.S. Eliot. Some of our group did know him, but on the whole it was mainly Allen Tate who had a real association with T.S. Eliot. Eliot’s word went out everywhere. You weren’t supposed to like Milton, for instance. This was ridiculous, but people listened to it and obeyed it in a certain sense. People were awestruck by his authority in literary matters, and he spoke with great authority. I think he was a good influence on the whole.

Chapter 16: You talked about the support of other writers. Is that part of what motivates you to go to things like the Sewanee Writers’ Conference?

Spencer: I don’t know what motivates me. It’s about the best-known writers’ conference in the States, I think. It has built itself up beautifully. I got an honorary degree from Sewanee, and the various trips I have made there for special occasions have always been a delight. I just like to go there. I’ve met Wyatt Prunty in other, different locales, and I think he’s a fine organizer for that. The people he has back every year have gotten to be—somehow you go to these things, like, I belong to the American Academy that meets in New York once a year, and I was going for a long time just because I could see people there I couldn’t see anywhere else. A lot of them have quit going now; I may not continue. But every year you go up there and you meet a lot of people you wouldn’t see otherwise, and so the same thing prevails about Sewanee. I like to go there.

It’s a bit of a job, though. You’ve got to fly to Nashville, and they meet you and drive you up there. You spend the night and do your stuff the next day, and then you spend the night and have to be driven back to Nashville and get the plane home.

Chapter 16: Sewanee is kind of tucked away.

Spencer: Yes it is, but that gives it a very special feeling, I think. It’s sort of a place of renown, and also there’s something kind of very poetic about it.