Fragile

A baby’s life-threatening illness brought Hamilton Cain a new understanding of his own childhood

For five years, Hamilton Cain never knew what his son Owen was thinking. Diagnosed with a debilitating and degenerative genetic disease called Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Owen did not have the strength to breathe, speak, or move on his own. On a whim, a nurse put a pen in his hand one day and discovered that Owen could read and understood much more about the world and his family than his father had hoped was possible. Owen needs his father’s hand to steady the pen as he spells out simple snapshots of a life: Running is freedom. Happy you are here now. You are the reason I am good. Until then, Cain only sensed that his son shared his own thwarted wanderlust and had a particular passion for outer space. From the teary way Owen always looked at him when they watched a documentary about Voyager 1, Cain wondered if Owen didn’t feel like a satellite far off in space, orbiting the home on which he could never land.

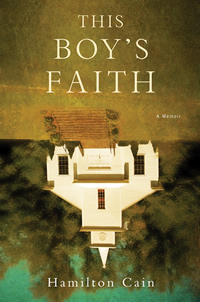

This Boy’s Faith is the story of a father who learns what it means to be faithful through raising his medically fragile son. Hamilton Cain is a natural storyteller. During his adolescence in Chattanooga, his way with words convinced his conservative family that he was anointed to preach. But it also gained him entry into a wider and more challenging world than the one offered by his strict Southern Baptist childhood: after college at the University of Virginia, Cain became a journalist in New York City.

In the memoir, Cain describes the places, beliefs, and people who inhabited his former and current homes. He writes in the voice of a man who has always been able to weave life’s experiences, however transient, into his own larger narrative, whether they are the scripted ones of his youth or the self-determined ones of his adulthood. But the birth of his first-born son and the fight for a full life for Owen sends Hamilton Cain on a search to discover what liberation and affirmation can be found in his own childhood. Though it was a life defined by faith and confined by fear, it somehow taught him how hope can live in the beauty of a world—and a child—that defies all expectation.

In the memoir, Cain describes the places, beliefs, and people who inhabited his former and current homes. He writes in the voice of a man who has always been able to weave life’s experiences, however transient, into his own larger narrative, whether they are the scripted ones of his youth or the self-determined ones of his adulthood. But the birth of his first-born son and the fight for a full life for Owen sends Hamilton Cain on a search to discover what liberation and affirmation can be found in his own childhood. Though it was a life defined by faith and confined by fear, it somehow taught him how hope can live in the beauty of a world—and a child—that defies all expectation.

In a recent email exchange, Cain answered questions from Chapter 16 about becoming a “part of humanity’s larger story” through the process of becoming a parent, writing a memoir, and discovering the ways generations pass on more than their DNA to those who follow.

Chapter 16: “Sacrifice, Steadfastness, Redemption, Apocalypse, Magic. Still clinging to me like burrs, after all these years.” In This Boy’s Faith, you describe the way a deeply religious childhood still resonates in a secular adult life long after any consent to belief is gone. Why did you choose these religious concepts as themes for your particular story?

Cain: This book had a peculiar evolution: it started out as a magazine article on how doctors navigate religious differences in hospitals and in other clinical settings. I interviewed MDs from a range of faiths—Muslim, Jewish, Catholic and evangelical Protestant—and then laced the piece with a few recollections. My editor responded more to the personal material than to the medical stories, and asked me to recast the piece as an essay, which wrote itself in a couple of days and then eventually morphed into my “Fall Creek Falls” chapter. Much later, after I’d convinced myself (and, more importantly, a literary agent and a publisher) that this was a viable memoir, I planned to write a straightforward coming-of age along the lines of Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, Shalom Auslander’s Foreskin’s Lament, or Rhoda Janzen’s Mennonite in a Little Black Dress. Fairly late in the writing process, though, I realized I was wrestling with a deeper internal debate about values, especially those that were rooted in my religious childhood and that had somehow bled into my adult life, so removed, geographically and emotionally. In some sense, then, I didn’t choose these religious concepts as my themes; they chose me.

Chapter 16: The book begins with an attempt to turn to religion after Owen is diagnosed with a life-threatening illness. You walk into a church, albeit a more progressive one than your Southern Baptist roots offered, and have visceral reaction: “Like an emigrant returning to the old country … I felt I’d come home.” The rest of the book explains what that old country was like and why you left it. How would you describe your current relationship to religion?

Cain: As the book shows, I grew up in a family that attended services several times a week, spring, summer, fall, winter. We were chronic churchgoers—it defined us, almost to an obsessive degree. As a young adult I drifted away from it but later, when confronted with my baby’s devastating and potentially fatal disease, I felt the need to plug in, charge the internal batteries. And I still feel drawn to it—it’s the most natural thing in the world for me to sit in a pew, listening to choral music or a sermon.

Cain: As the book shows, I grew up in a family that attended services several times a week, spring, summer, fall, winter. We were chronic churchgoers—it defined us, almost to an obsessive degree. As a young adult I drifted away from it but later, when confronted with my baby’s devastating and potentially fatal disease, I felt the need to plug in, charge the internal batteries. And I still feel drawn to it—it’s the most natural thing in the world for me to sit in a pew, listening to choral music or a sermon.

But only up to a point. I still stumble on excruciating debates that make me want to run for the hills: who’s going to heaven, who’s not, the role of women in the church, why God wants us to repeal healthcare reform, etc. Enough to induce a migraine. I’ll leave those thorny arguments and wooly questions to the theologians—ultimately, I’ll stick with literature and public policy, my proper home.

Chapter 16: Caring for a child with a chronic illness and no easy course of treatment would be challenging for any parent, no matter his belief system. How has Owen’s illness altered your assumptions and changed your perspective of the world and who you wish to be in it?

Cain: Owen’s illness completely upended my life, and my wife’s, jolting us from the seamless orbits of jobs and friends and routines. We now plot each day around respiratory treatments and catheters and feeding tubes. We’ve had to work very, very hard to help him. There’s really no adequate way to describe the arduous physical labor that goes into the care of a medically complex child. These experiences have challenged me to tap into hidden wells of my character, same with my wife—we’re definitely stronger, better people because of what we’ve learned from Owen.

Chapter 16: In your book, you describe the quirky and confining world view of your Southern Baptist childhood. Even after so many years, you are intimately aware of the internal struggles of the people you knew in that community. As you’ve escaped to the more complex world of your adulthood in New York, have you been able to build a community that serves the same role for you that the church served for your family?

Cain: I’m a social person; and because I’ve lived in New York for almost 23 years, I’ve bumped up against an endless array of communities. I’ve loved them all, from the cuisines—Indian restaurants on the Lower East Side, a favorite Nigerian place in Soho, Chinese takeout in the Village, Middle Eastern bakeries in downtown Brooklyn, a gourmet Mexican restaurant in Park Slope—to concerts and art exhibits and impromptu dance performances on subway platforms. Always a carnival, New York. And consider the plurality of languages: in my neighborhood alone, within a diameter of just a few blocks, one can hear Russian, Arabic, Spanish, Bengali, Yiddish, Polish, French and Italian. That magnitude of diversity just works for me, and always has.

By contrast the community that nurtured me as a child was far more homogenous, but it still serves as a kind of primal template of bonds and alliances and rivalries that are inherent to any community. I can see glimpses of my Baptists today, even in my raucous, frenetic, multicultural city.

Chapter 16: In this book and in articles for Men’s Health, you write about the communication gap between parents and their adult children. Owen’s medical condition poses barriers to communication, too. Has experiencing the world together with him in any way changed the way you see the barriers between you and your own parents?

Cain: The experience of becoming a parent—first to Owen, and then to his younger twin brothers—has immeasurably expanded my sense of the parent-child relationship. I feel like I’m part of humanity’s larger story. And in crucial ways my children have swept away some of the barriers that had sprung up between my parents and myself, like weeds. For instance, in one chapter I describe a moment when my sister disappeared from our tour group in Carlsbad Caverns, how my mother recoiled into sheer terror for the hour my sister was missing. And not long after I’d written the scene, one of my six-year-olds vanished during a kindergarten pick-up—somehow he’d slipped by me in a crowd, crying and confused. I found him about five minutes later, held down by a crossing guard at a perilously busy intersection. I aged about five years in those five minutes—and came away with far more empathy for what my mother had felt decades earlier.

Chapter 16: You write about the liberation you experienced in college when you embraced the Socratic principle that “an unexamined life is not worth living.” Breaking free by embracing a more expansive world of ideas and by moving far away from the family and the forces that shaped you was essential to your journey. Your memoir ends with a vision in the distance: “Owen: his desire to be an astronomer someday, floating beyond the cramped cell of his body.” Did writing this book about the trajectory of your own life affect your feelings about and understanding of Owen’s life? Has it changed your understanding of a father’s role in introducing him to the world?

Cain: I’d say that the writing process has given me a deeper appreciation of generations, how parents pass along more than just their DNA to their children. The voices and rituals and textures of childhood cling to the adult even as new ones move in to shape his or her sense of purpose in the world. There’s something both mysterious and gratifying to look back at myself as a child, peering down a long, long telescope to discover remote moments and memories just about to wink out, like waning galaxies, little bits and pieces of me that now live and breathe in my children.

My trajectory informs Owen’s but also remains distinct from his. Trust me: he’s his own guy, with a wry sense of humor and a passion for topics that don’t come easily to his parents, alas. I’m certain I’d still be doing all I could for him had I not written the book, but the nature of our relationship—and my relationship with my wife and other children as well—has grown richer because I chose to build this house, plank by plank, sentence by sentence.