Don't Read This

Chapter 16 talks with Pseudonymous Bosch about being a riddle wrapped in an enigma published in a book

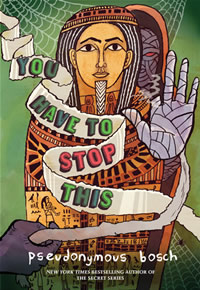

Ask any grade-school kid an innocent question about a Pseudonymous Bosch novel, and prepare to be stonewalled: Bosch’s books lure the reader into a conspiracy of silence, in which the author, characters, and plot are all secrets. In fact, Bosch’s entire Secret Series—the fifth and final installment, You Have to Stop This, will be published on September 20—is the apotheosis of what might be called the “reverse psychology” school of children’s literature: warning kids away from the dangerous book they’re presently holding is a surefire way to get them to crack its spine.

Like Lemony Snicket, whose A Series of Unfortunate Events proved beyond a doubt that kids will gobble with relish the very books that are supposed to be bad for them, Bosch knows how to set a literary hook. His publicity juggernaut, including a pseudo-blog, pseudo-tweets, a Facebook page, information leaks, and appearances and readings by a soi-disant imposter, brilliantly straddles the line between self-promotion and self-effacement, and expertly converts his youthful readers into co-conspirators.

Prior to his appearance at the Southern Festival of Books, Chapter 16 interviewed the mysterious author—or someone claiming to be him—by email.

Chapter 16: Your obvious literary antecedents (would it be fair to call them influences?) from recent years must include Lemony Snicket (author of the A Series of Unfortunate Events series) and Jon Scieszka (author of The Stinky Cheese Man, which shattered the fourth wall of picturebookdom). I wonder if you are old enough to have grown up reading Ellen Raskin, whose The Mysterious Disappearance of Leon (I Mean Noel) and The Tattooed Potato and Other Clues remind me very much of your books. Any other literary influences?

Pseudonymous Bosch: Alas, I did not grow up reading Ellen Raskin and have only read her wonderful books very recently. I would say that, from childhood, my most pertinent literary influences remain Sherlock Holmes on the one hand and Roald Dahl on the other. These are mixed in the stew of my authorial unconscious with an unhealthily large dose of post-structuralist readings from college. What comes out—well, I will let others describe that particular concoction.

Pseudonymous Bosch: Alas, I did not grow up reading Ellen Raskin and have only read her wonderful books very recently. I would say that, from childhood, my most pertinent literary influences remain Sherlock Holmes on the one hand and Roald Dahl on the other. These are mixed in the stew of my authorial unconscious with an unhealthily large dose of post-structuralist readings from college. What comes out—well, I will let others describe that particular concoction.

Chapter 16: In The Name of This Book is Secret, you reveal the raison d’etre for your books: “I can’t keep a secret. Never could.” Tell us, Pseudonymous Bosch, how you manage to ensure that your many minions—publishers, editors, agents, publicists, and even your “impostor,” who tours the country reading and tirelessly promoting your books—can keep your identity secret?

Bosch: Who are these minions you speak of?! I am appalled by what you suggest. Tirelessly promoting my book, indeed! Where are they? I shall fire them immediately.

Chapter 16: Of course, there will always be rumors. One reads, for instance, that the writer known as Pseudonymous Bosch is, in fact, a 43-year-old man named Raphael Simon. (A link to the reputable British newspaper The Guardian stating as much appears on your own pseudo-blog, as a matter of fact.) Is this a vicious lie, a deliberate effort to mislead, or simply one more testament to the fact that it is impossible to hide anything for long in the twenty-first century?

Bosch: It seems clear that Raphael Simon, unlike the self-evidently honest Pseudonymous, is a fictitious name. But who or what lies behind it? I cannot say. For a while I thought it was a Frenchwoman named Leah Par (Raphael Simon backwards: nom is Leah Par). More lately, my suspicions have fallen on a certain childhood nemesis….

Chapter 16: My son received The Name of This Book is Secret for his ninth birthday last week, and polished it off in one sitting. He then reached for If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late, which he finished last night, and This Book Is Not Good For You is sitting on his bedside table. Were you, too, a literary glutton as a child? Which books did you devour most avidly?

Bosch: Glutton, certainly. Though literary seems too exalted a term. I read constantly—at the dinner table, in class, in bed, on the school bus. I read whenever and wherever I could—and often whenever and wherever I shouldn’t. As to what I read, the answer is everything. From the aforementioned Holmes and Dahl to Ursula Le Guin and J.R.R. Tolkien. And was that me reading Little Women and Little House on the Prairie on the bench at lunchtime when the other boys were playing kickball?? Er…yes, it was.

Bosch: Glutton, certainly. Though literary seems too exalted a term. I read constantly—at the dinner table, in class, in bed, on the school bus. I read whenever and wherever I could—and often whenever and wherever I shouldn’t. As to what I read, the answer is everything. From the aforementioned Holmes and Dahl to Ursula Le Guin and J.R.R. Tolkien. And was that me reading Little Women and Little House on the Prairie on the bench at lunchtime when the other boys were playing kickball?? Er…yes, it was.

Chapter 16: The character Max-Ernest has parents who are quite unusual: they are congenitally unable to agree (which is why Max-Ernest has two names) and have divorced, split their house in half, reunited, and re-divorced. This seems like exactly the sort of plotline that children would shrug off and accept but that adults might find unnecessarily “disturbing.” Can you comment?

Bosch: Not without insulting adults.

Chapter 16: “The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author,” Roland Barthes famously wrote. Do you agree?

Bosch: Absolutely. That is why I am so resentful of my readers.

Chapter 16: Speaking of death, the forthcoming You Have To Stop This is billed as the final installment of the series. Will Pseudonymous vanish when his books cease to be written? Will he reveal his true identity at last? Will he continue to write, the better to satisfy his voracious readers and co-conspirators?

Bosch: Ah, but according to Barthes, it is when I write that I vanish! Actually, I think I have found a way around this conundrum. In the future, I am going to make my readers write my books. Seriously. My first book after the Secret Series is going to be a Do-it-Yourself mystery novel called Write This Book! Will the book at last replace the Death of the Author with the Death of the Reader? Hmm, I guess you’ll have to read—or rather write—the book to find out. If you’re brave enough, that is.

Pseudonymous Bosch will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.