Inside the Story

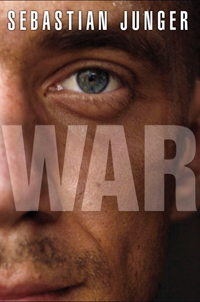

Sebastian Junger talks with Chapter 16 about his latest book, War, and the dangerous business of reporting it

At this year’s Academy Awards ceremony, Esperanza Spalding sang over a montage of photographs of film-related men and women who had died in the past year. One of those photographs featured Tim Hetherington, nominated for a Best Documentary Oscar in 2011. Hetherington was killed last April in Libya while photographing the uprising against Moammar Gadhafi. His Oscar nomination came for Restrepo, which he created with journalist and author Sebastian Junger. The film follows a platoon of the most active combat unit in Afghanistan during 2007 and 2008. Junger first told their story in a series of magazine articles, photographed by Hetherington, for Vanity Fair. In 2010 Junger brought out War, a full-length version of the story of being embedded for weeks at a stretch with young men who faced constant enemy fire, hunkered down in one of the most inhospitable places on Earth, the Korengal Valley, just north of the Khyber Pass.

A few days before the Academy Awards remembered Hetherington, American journalist Marie Colvin and French photographer Rémi Ochlik were killed while covering the civil uprising in Syria. The nonprofit Committee to Protect Journalists confirms that 2011 was one of the deadliest years for journalists on record, and so far 2012 appears even worse. Junger, who will deliver a lecture on “Dispatches from War: Stories from the Front Lines of History” at Middle Tennessee State University March 20, recently spoke withChapter16 by phone from his car as he drove toward New York, where he lives and is the co-owner of a pub, The Half King.

Chapter 16: Why do war correspondents take such risks? Why do you do it?

Junger: The Arab spring opened up this whole area of danger because there was full access to frontline combat, and that’s usually not true. It’s usually quite hard to get into combat as a journalist. Nobody wants journalists around in combat. In Bosnia and Sarajevo, it was almost impossible to get out to the front lines. I mean, you could always get hit by a stray mortar. But there were very, very few journalists in combat.

Junger: The Arab spring opened up this whole area of danger because there was full access to frontline combat, and that’s usually not true. It’s usually quite hard to get into combat as a journalist. Nobody wants journalists around in combat. In Bosnia and Sarajevo, it was almost impossible to get out to the front lines. I mean, you could always get hit by a stray mortar. But there were very, very few journalists in combat.

With the Arab Spring, all of a sudden these kids with no idea what they were doing were just jumping into pickup trucks. And if you were there, you could jump into one, too, and off you went, and no one had a clue what they were doing. So a lot of people got killed—not just journalists, but rebels too. It was a war of complete unprofessionals.

I think there’s a sort of a large amount of ego in it, frankly. It’s a very flattering job to have. People admire you if you’re a war reporter. It feels nice to be admired. I think there is a component of, “These are terrible things, and the news needs to get out, and someone has to do it, and I’m lucky enough to be that person.” For some, there’s a certain amount of youthful thrill-seeking, of proving one’s self. When I went to Sarajevo I was a young man, and I think young men definitely have a very ancient impulse to prove themselves as men. War is a clichéd way to do it, but in some way it works, so there is a bundle of different motivations.

Chapter 16: One of the things that we hear about the way war today is different from wars in the past is that soldiers are on the Internet, reading email and staying in touch with the outside world. Was it like that for the soldiers you wrote about?

Junger: Not for them. They would go weeks at a time without any email or phone or anything. But I should add as a matter of sort of general principle that journalism in the old days, in the ‘90s, took place in developing countries that had very, very poor communication. There was no Internet, no cell phone. When you went to Sierra Leone you were really in Sierra Leone. And you didn’t have much access to your editor, your family, your girlfriend, whatever. As a journalist, having communication—that’s a very new thing. Psychologically, it changes the experience. And I’m sure for a college student, for their year abroad or whatever, it also changes the experience if you can just call home any time you want. In the old days you had to wait for a letter to come. So all that has changed a lot, for many soldiers, too.

Chapter 16: Your best-known works, The Perfect Storm and A Death in Belmont, were research-heavy projects, where you were digging into the past in various creative ways, but as a war reporter, you’re right there in the middle of it. How does that experience translate into the writing? Does it change the way you approach the work?

Junger: Well, I’ve never really written in first person before, other than the odd paragraph here and there. I was living in Gloucester when the storm hit. I think there is one mention of that fact in all of The Perfect Storm. Otherwise there is no first person, no reference to myself, my own life, my own thoughts. So if you experience in an extensive way the story you are writing about, then putting yourself and your thoughts, your reactions, into the story is completely natural. It illuminates the story in ways that a strict sort of journalistic third person couldn’t.

You have to be honest. Just because you are inside the story doesn’t mean you can pretty up your emotions, pretty up your responses to be more flattering. You really have to be honest about the embarrassing stuff, the noble stuff, the ugly stuff, and whatever. The way you respond to that situation is very, very revealing of the situation, but it’s not if you sort of try to doctor it up at all to try to make yourself look better.

Chapter 16: Once you’ve jumped into that sort of experience, does it make it hard to go back to the straight third person?

Chapter 16: Once you’ve jumped into that sort of experience, does it make it hard to go back to the straight third person?

Junger: Certainly the writing is easier. I wrote War in six months, which is very fast for me. It was a very emotional experience, writing the book. That emotion produced very rapid writing. It was the first time words just poured out of me. Emotions poured out of me. They never had before. A Death in Belmont was much more of a chess game. I was juggling an enormous number of very, very complex facts and trying to order them, trying to be rational and methodical. It wasn’t an emotional experience, particularly.

I haven’t started another book project, so I don’t know what it’s going to be like. But frankly there aren’t that many experiences I can imagine having that would be as intense and powerful and emotional as the one I had out in Korengal. It could be I could try to write another first-person book about something that is less emotionally charged for me, and it wouldn’t come tumbling out like War did. I think it all came tumbling out, not because it was first person, but because of the content.

Chapter 16: Because of the way you shared the risk with the soldiers you were writing about, do you feel that you bonded with them in a way that’s unusual for a journalist and subjects?

Junger: Certainly, just as a general truth, the more time you spend with people the more closely you bond with them. Most journalists do not spend a total of five months that I spent out there. Tim spent five months with them also. Just the math alone produced a closeness that most journalists don’t experience. Most journalists are on a clock. This business is broke. Newspapers can’t afford to have journalists spend five months on a story. Vanity Fair, though, is not a news gathering organization—it’s a glossy magazine. So if they have a reporter out in the Korengal off and on for a year, it’s fine. It doesn’t matter. That was easy for them. Standard news organizations couldn’t even contemplate doing what Vanity Fair did.

Chapter 16: What do you think it means for the future of long-form journalism that only a handful of magazines can pay for it anymore?

Junger: I think it’s fine to divide it up. What I did was not news. What I wrote had no relevance to the bigger picture of Afghanistan or strategic errors or the rationale for war. It just wasn’t a comment on that. I think you can do a standard newspaper tour of the war in Afghanistan and come back with some valuable truths about the strategy, about the overall conduct of the war. The thing that newspapers don’t get to do is to find out how soldiers feel. In some ways that’s an important topic, but it’s not really news. So if that gets left up to the occasional magazine reporter, fine. I don’t see that all news organizations have to do everything.

Chapter 16: Have you stayed in touch with men you wrote about?

Junger: Of course. Some more than others. Brendan O’Byrne the most. I kept in touch with them to the degree that I was close to them when I was out there. Some guys I haven’t got in touch with at all.

Chapter 16: Are they mostly back in civilian life now?

Junger: Not really. Maybe a third of them are out right now. Some are definitely hard core, in for life. These were not reluctant National Guardsmen; these were guys who dropped everything they were doing as soon as they turned eighteen and joined the most hard-core unit they could possibly get into. It’s very different from some other units. They really see themselves as soldiers and they’re very proud of it, so a lot of them are probably going to stay in.

Chapter 16: There is a great line in the book, “Combat is the smaller game that young men fall in love with.” These are the kind of guys who fall in love with that game?

Junger: Yeah. That’s right. You know, they burn out on it, too. After three or four deployments, I think those guys are probably quite happy to maybe not deploy again. Now they are in their late twenties; a lot of them are married [and] have kids. They’re in a different place than they were eight years ago when they joined. These were eighteen-year-olds who really wanted to experience combat, and they had to work very, very hard to get into a unit that would give them that combat.

Chapter 16: Many colleges and universities have adopted War in common reading programs. How have these young readers, the same age as the guys you write about, responded to the book?

Junger: I think they’re sort of amazed at what’s happening out there. I think the nation as a whole has a kind of Vietnam-era take on the military and on war. I think it’s probably sort of eye-opening to a lot of young people that the men—and it is mostly men who are in combat overseas—were at least at one point excited by the prospect and joined willingly. It really is a football team. I think it’s very easy to sort of say, Oh, those poor guys, because then you don’t have to feel empathy for them.

It’s a little more complicated when they realize, Wow, some people choose to go to college, and some people choose to go to war. That’s a different dynamic than a nation with a draft. There’s kind of nothing to protest if the entire army is volunteer. It changes the conversation.

Chapter 16: Will you be going back into a combat zone?

Junger: No, I’m not going to be doing that any more. Tim got killed in Libya last April, and I just decided that was a good warning sign. It felt like I’d lost my first hand at the poker game and it was time to leave. I never would have had this reaction twenty years ago. I just turned fifty. I thought it was going to be like, OK, I won’t do that again, but goddamn I’m gonna miss it. I really don’t. It’s funny. I really just don’t, which I take to be a good, healthy sign, some form of maturity.

Chapter 16: Do you find yourself thinking at odd moments about the IED that hit your vehicle?

Junger: Yes, I do. It’s hard for me to know—I’ve asked people who know a lot about explosives—and it’s hard to know whether it was just an under-powered bomb that ultimately the armoring in the Humvee would have protected us against, or if it really was a matter of ten feet, and had it gone underneath us it would have really messed us up. So it’s hard to know if I barely escaped an awful experience, or if they just didn’t put enough powder in the thing, and it never would have hurt us. I don’t know which it is. I don’t think about it that much anymore, but I certainly thought about it a lot afterwards. There’s a lot of things in war like that. There’s a lot of things in life like that. When you realize a lot of this stuff’s random, that’s a hard thing to reconcile with the idea that you have some say in your life.

Sebastian Junger will appear at Middle Tennessee State University’s Tucker Theatre in Murfreesboro on March 20 at 2:40 p.m. to deliver a free public lecture entitled “Dispatches from War: Stories from the Front Lines of History.”