“A Nazi, a Treasure, a Murder, a Car Chase, and Two Fistfights”

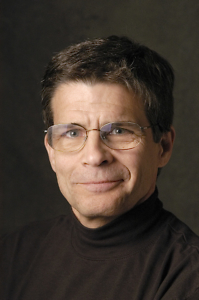

Daniel Friedman talks with Chapter 16 about his Memphis family—and which of his grandfathers inspired the octogenarian ex-cop who’s the hero of his new mystery

In his new mystery, Don’t Ever Get Old, Daniel Friedman spins an engrossing tale of intrigue, but that’s only one element of what makes this acclaimed debut so notable. He also manages to write page after page of hilarious—and sometimes poignant—commentary by an octogenarian ex-cop named Buck Schatz, a Jewish guy from Memphis who finds himself on the hunt for the Nazi war criminal who nearly killed him during World War II. Friedman is now a lawyer practicing in New York, but he grew up in Memphis. Friedman’s three surviving grandparents still live there, and his mother, Elaine Friedman, teaches deaf students at White Station High School, which Friedman also attended. He recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You now live in New York, but you clearly have deep roots in Memphis. Tell us about your grandparents.

Daniel Friedman: Buddy and Margaret Friedman are ninety-six and ninety-four. Buddy was born in Memphis, and so was his mother. Goldie Burson, eighty-six, is from Brooklyn, but my late grandfather, Sam Burson, was born in Memphis. My father was Robert M. Friedman, who was a prominent Memphis lawyer. He died in 2002. My mom’s name is Elaine. She teaches the deaf.

Chapter 16: Would you call either of your grandfathers a direct inspiration for Buck Schatz?

Friedman: He was based to a certain extent on Buddy Friedman, especially in the first drafts of the first scenes I came up with, which were the opening chapter, the funeral scene and the scene in the bank. But he changed a lot as I built the story around him and revised it. Buddy shares almost none of Buck’s biographical details. Buddy was not a cop; he served in the Pacific, not in Europe; he was never a POW.

The idea behind Buck’s backstory was that I imagined that there was a series of fairly lurid ‘60s-era pulp novels about Buck, and now we’re revisiting him as a very old man. I definitely had movies like Dirty Harry and Bullitt and Death Wish in mind, as well as characters like Sam Spade from Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and the Continental Operative from Red Harvest. There’s also some Quentin Tarantino influence in there.

A lot of the details about assisted-living facilities and dementia were derived from my experience with my great aunt, Rose Burson, who died in 2010 at the age of eighty-eight.

Chapter 16: Is Buddy as funny in real life as Buck is in your novel?

Friedman: I asked Margaret, my grandmother, what she thought about this. She says Buddy is funny in his way, and he can definitely be acerbic. A neighbor came by their house the other day to see if they still had their copy of the previous Tuesday’s newspaper. Margaret had already put the recycling out on the curb, but Buddy invited the neighbor to root through the trash at her leisure.

Friedman: I asked Margaret, my grandmother, what she thought about this. She says Buddy is funny in his way, and he can definitely be acerbic. A neighbor came by their house the other day to see if they still had their copy of the previous Tuesday’s newspaper. Margaret had already put the recycling out on the curb, but Buddy invited the neighbor to root through the trash at her leisure.

What I got from Buddy is just a piece of what ultimately goes into Buck. Obviously all the jokes that are derived from Buck’s police career have nothing to do with my grandfather, who I’ve never known to be a violent man. And Buddy doesn’t smoke; my dad inspired most of the chaos Buck causes with his cigarettes. The sadder stuff is completely invented, or derived from my experience, because I would never have those conversations with my grandparents.

If anyone is as funny as Buck, I’d like to think it’s me, but Buck benefits from the fact that everyone he encounters exists primarily to set up his zingers.

Chapter 16: There’s a lot going on in your book. Do you consider Don’t Ever Get Old a typical genre novel, or were you consciously aiming to include elements more commonly associated with literary fiction?

Friedman: I don’t want to use the term “literary,” although I guess I don’t mind if other people do. I think, to some readers, the notion that a novel is literary implies that it is hard to read. I try to make my prose look nice and sound pleasant, but I’m not the sort of guy who will sit at his keyboard all night trying to write an intricate, gossamer sentence that unfolds like a paper flower on the glassy surface of a still pond. I learned a lot about writing in law school, and lawyers have got to write in short, simple declarative sentences, because they’re trying to communicate with an audience that is 1) barely paying attention and 2) a judge. If you flip open Don’t Ever Get Old in a bookstore, you’ll see short paragraphs, short chapters, lots of dialog, and plenty of white space.

However, I’ll admit to a certain degree of ambition. A lot of genre novels are primarily concerned with mechanics, and carrying the reader along with the momentum of the plot to its conclusion. I think the stuff that happens in these stories is always less interesting than the people who make things happen, and I’m always looking for a good opportunity to unpack the characters and explore their motivations. A strong plot engine is a useful tool to keep a novel from bogging down, as long as the stuff that happens is derived from the characters’ actions, rather than being foisted on them from outside the story. But the plot is a method, not a purpose. Don’t Ever Get Old has a Nazi in it, and a treasure and murder and a car chase and two fistfights. But the book is really about finding out who Buck is at this point in his life.

Chapter 16: You’re pretty young for a debut novelist. When did you start to become interested in mysteries? When did you start writing?

Friedman: When I was in high school, I thought I wanted to be somebody like Hunter S. Thompson or David Foster Wallace. This was, of course, back before both of those guys killed themselves. I majored in journalism at the University of Maryland, and I had an idea that I was going to go out and write long-form magazine features. But my dad died the summer before my senior year, and I wanted security. And then a distinguished and admired young alumnus of the Maryland journalism

school, a guy named Jayson Blair, went and got famous in exactly the wrong kind of way. So if you were trying to get a job coming out of Maryland in 2003, all anyone would ask about in interviews was Jayson. I went to law school.

In 2007, my firm shipped me out of town for the summer to work on a project that mostly involved reading years and years of the client’s old e-mails to see which ones were privileged. I was working about twelve hours a day, six days a week, and I didn’t want to leave my hotel room the rest of the time, so I started writing, and I got a good start on the book. It still took me two years to finish the thing, and I signed with my literary agent in November 2009. Apparently, the publishing industry just sort of stops answering e-mails between Thanksgiving and Christmas, so we waited until around Valentine’s Day to submit the manuscript, just to be safe. Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press offered on it soon after.

The first scene I wrote for Don’t Ever Get Old is the scene in the fourth chapter where Buck misbehaves at a funeral. Then I went back and wrote the first chapter, in which Buck is coerced into visiting a dying friend in a hospital. I didn’t know exactly what sort of book I was writing then, and I came up with the Nazi hunt to tie it together, and it became a mystery. I’m interested in exploring violence and loss as recurring themes in my stories, so crime fiction is a good fit for me.

Chapter 16: What current mystery authors do you admire most and why?

Chapter 16: What current mystery authors do you admire most and why?

Friedman: I’ve been reading John LeCarre and Elmore Leonard lately. Several reviewers have compared me to Leonard, and I hadn’t read him in a while, so I picked up all his books about Raylan Givens, the cowboy federal marshall who became the hero of the TV show Justified. Leonard’s novel Pronto was really clever. It set up three great characters: an old-school Sicilian gangster, a streetwise Miami bookie and Raylan the cowboy, and got them chasing each other all over south Florida and the Italian Riviera. It’s a lot of fun, and he makes it look easy, even though a story like that, with several major characters, is very complicated to organize. He’s very good at letting the conflict and the plot derive from the characters.

LeCarre definitely doesn’t make anything look easy. His spies unravel conspiracies by tugging at threads, one at a time. The complexity of the stories is really remarkable, and he’s an expert at turning quiet

moments into set-pieces. He can wring remarkable tension out of a situation in which a character walks down an empty hallway and steals some documents out of a file cabinet.

There’s also a writer named Rick Gavin who wrote a stellar book last year called Ranchero. It’s about a repo man in the Mississippi delta who goes to collect a delinquent twenty-dollar payment on a rented flat-panel television, and the deadbeat hits him over the head with a fireplace shovel and steals the cherry 1969 calypso-coral Ranchero that the hero has borrowed from his landlady. So this guy spends the rest of the book trying to get his car back. It’s worth checking out. The sequel comes out later this year.

I’m also a big fan of a writer named Josh Bazell, who wrote Beat the Reaper and Wild Thing. Beat the Reaper is about a surgeon who is also a former mafia hit man in witness protection. When an acquaintance from his old life shows up in his hospital, he has to face his past. And Bazell, who is a doctor, came up with the best way of killing a guy that I’ve ever seen in a novel.

On June 7 at 6 p.m., Daniel Friedman will discuss Don’t Ever Get Old at the Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis. To read Chapter 16’s review of Don’t Ever Get Old, click here.