Dictionary as Southern Cocktail

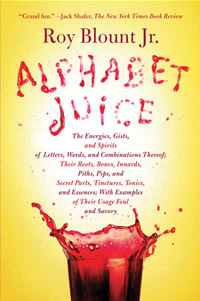

Popular NPR humorist and Vanderbilt graduate Roy Blount Jr. writes a contemplation of word etymologies that is both erudite and as funny as a skunk in the parsonage

Roy Blount Jr. is one of those rare writers whose actual voice has become almost as familiar as his literary one. Most weekends, you can hear his signature blend of Georgia drawl and rapid-fire wit on the National Public Radio quiz show Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me, and he periodically recites comical poetry and inflicts musical screeching (as founder of the fictional “Society for the Singing Impaired”) on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion. The Vanderbilt graduate has performed a successful Off-Broadway one-man show, appeared on several network television programs, and stayed busy on the college lecture circuit.

Despite all this talking, Blount has somehow managed to sit down and write twenty-three books, in a literary voice that, as Michael Dirda recently wrote in the The Washington Post, “neatly balances real learning with easy-loping charm.” He has a penchant for pithy puns and political petards (and periodic alliterative passages), and this facility for wordplay landed him yet another side gig as a usage adviser to The American Heritage Dictionary. Chapter 16 managed to catch up with Blount for a conversation his work, the South, and the state of American letters.

Despite all this talking, Blount has somehow managed to sit down and write twenty-three books, in a literary voice that, as Michael Dirda recently wrote in the The Washington Post, “neatly balances real learning with easy-loping charm.” He has a penchant for pithy puns and political petards (and periodic alliterative passages), and this facility for wordplay landed him yet another side gig as a usage adviser to The American Heritage Dictionary. Chapter 16 managed to catch up with Blount for a conversation his work, the South, and the state of American letters.

Chapter 16: What prompted you to write a dictionary (or, rather, sort-of-a-dictionary), and then write another one?

Blount: I have always wanted to write a book about words. When I picked up a textbook in Linguistics and found there the astonishing, to me, notion that the relation of words to their meaning is arbitrary, I had an angle. Language to me has never been an abstract proposition. After all, I picked it up from blood relatives, and from various other lively characters. The letters of the alphabet, themselves, have always been lively characters to me.

Chapter 16: Why did you give it that eighteenth-century subtitle?

Blount: That’s a seventeenth-century subtitle, a tribute to the subtitle of a book on manners by my (presumable) ancestor Thomas Blount, whose Glossographia was the first English dictionary to attempt etymology.

Chapter 16: What’s your earliest recollection of noticing the sounds and shapes and peculiarities of words?

Blount: I remember seeing the word “all” in my mother’s handwriting, and realizing I could read script as well as words in print. She had been teaching me to read by reading to me, among other things, the tales of Uncle Remus, old African trickster stories in respectfully spelled dialect, which captured the sound of speech on the page: the “Power to make the Paper speak,” as Daniel Defoe put it in another connection.

Chapter 16: Were you consciously aiming for the perfect bathroom book with Alphabet Juice, or was that serendipity?

Language to me has never been an abstract proposition. After all, I picked it up from blood relatives, and from various other lively characters.

Blount: No, I did not have bathroom reading specifically in mind, but I welcome it with open arms.

Chapter 16: You have written often—and hilariously—about being a Southerner who chooses to live in the North. Do you have any habits designed to keep close to your Southern roots?

Blount: I go South a lot. Within any given couple of years I will have been at least once to New Orleans (my favorite place), Nashville (where I went to college), the Florida panhandle (where my father’s people come from), Oxford (my mother was from Mississippi), Austin (where my sister lives), Chapel Hill (where my daughter and son-in-law and grandchildren live), Chattanooga (where the Fellowship of Southern Writers meets), the Smokies, Tarpon Springs, and my home town of Decatur, Georgia. I have good friends in all those places, and also in Memphis, Charleston, Mobile, and Aiken.

Chapter 16: You’re the author of twenty-three books, a former president of the Author’s Guild, and a longstanding member of several writers’ organizations. How would you describe the current state of American publishing?

Blount: The current state of publishing is up in the air. I hope I don’t live to see the day that it is all on the Web.

Chapter 16: Along the same lines, for much of your career you have been one of the more prolific magazine freelancers in the country, with many of your stories later collected into books. How has the current crisis in the magazine industry affected you and your work?

Blount: I’ve enjoyed writing for magazines over the years, but I don’t do it much lately. Fortunately I’ve never had to depend on one medium for my living. When I haven’t had a book to write, I’ve had speeches to make, and vice-versa. So far. And then there is the trickle of revenue that is public radio.

Blount: I’ve enjoyed writing for magazines over the years, but I don’t do it much lately. Fortunately I’ve never had to depend on one medium for my living. When I haven’t had a book to write, I’ve had speeches to make, and vice-versa. So far. And then there is the trickle of revenue that is public radio.

Chapter 16: What do you think this means for American writers and readers?

Blount: The Web is running a lot of print media out of business and replacing them with opportunities for writers not to get paid. So it’s a lot harder for freelance writers to support themselves now, not that it was ever more than narrowly feasible.

Chapter 16: You are founding member of the Rock Bottom Remainders, the all-writer rock band which member Dave Barry has described as playing music “as well as Metallica writes novels.” The band recently announced that it is disbanding. Any plans for a reunion tour?

Blount: It’s hard to get everybody together since we range geographically from Miami to San Francisco to Maine. Not to mention all out of key.

[This article originally appeared, in slightly different form, on November 12, 2011, in connection with an earlier event.]

Roy Blount Jr. will appear at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville on March 26 at 8 p.m. in the Mabry Concert Hall. The event is free and open to the public.