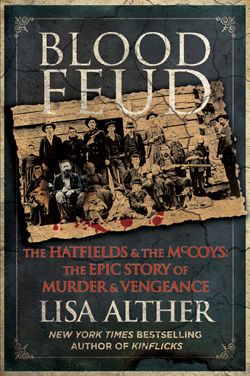

Too Many Guns and Too Much Moonshine

Kingsport native and bestselling author Lisa Alther takes on the legendary Hatfields and McCoys

In January 1865, Harmon McCoy, a thirty-seven-year-old father of four with another child on the way, was murdered in cold blood by members of the Hatfield clan when he was just steps away from the cabin he shared with his family. This incident is generally agreed to be the opening salvo in the domestic disaster that would come to be known as the Hatfields and McCoys. Harmon McCoy was a Union soldier returning from the Civil War, and his assassins seem to have been motivated by animosities left over from the war: the Hatfields tended to side with the Confederates, although most of them were also deserters.

Geography played a role in the feud, too. According to one report at the time, “It is a region which develops eccentricity of character and excessive independence of thought.” The Tug Fork River flows along the border of Kentucky and West Virginia, and the Tug Fork Valley of the 1800s was a pristine yet forbidding landscape whose inhabitants were constantly at the mercy of disasters both natural (floods, crop failures, epidemics) and man-made (thefts, attacks, kidnappings). The area attracted settlers on the fringes of society with little or nothing to lose. “In a largely lawless wilderness with few schools, churches, courts, or doctors, people were on their own,” Alther writes, “and a man’s reputation for violence was often what protected his family and animals from harm.”

This unstable environment bred two fascinating and ultimately infamous family patriarchs: William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield, born in 1839, and Randolph “Ranel” McCoy, born in 1825. (Hatfield’s unusual nickname apparently derives from McCoy’s description of him as “six feet of devil and 180 pounds of hell.”) At the height of the feud, thirty-five Hatfields and forty McCoys were locked in a bitter give-and-take that resulted in as many as two dozen feud-related deaths over a twenty-five year period, depending on the narrowness of your definition of “feud-related” deaths. As tragedy followed tragedy, many more lives were affected—and effectively shortened—than only those who bled out from mortal knife or gunshot wounds.

This unstable environment bred two fascinating and ultimately infamous family patriarchs: William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield, born in 1839, and Randolph “Ranel” McCoy, born in 1825. (Hatfield’s unusual nickname apparently derives from McCoy’s description of him as “six feet of devil and 180 pounds of hell.”) At the height of the feud, thirty-five Hatfields and forty McCoys were locked in a bitter give-and-take that resulted in as many as two dozen feud-related deaths over a twenty-five year period, depending on the narrowness of your definition of “feud-related” deaths. As tragedy followed tragedy, many more lives were affected—and effectively shortened—than only those who bled out from mortal knife or gunshot wounds.

Other families in the region also acted on murderous grudges. “What set the Hatfield-McCoy feud apart from all the others,” Alther writes, “was its built-in plotline.” Following Harmon McCoy’s murder, the two families were drawn into a dispute over stolen livestock. Years later, one Hatfield descendent declared that “the entire feud could have been avoided if only Floyd Hatfield had barbecued that wretched hog and invited everyone to supper.”

Next was a star-crossed romance between Johnse Hatfield and Roseanna McCoy, a love story that ended in desertion, a child dead in infancy, and at least one broken heart. This incident was later characterized by the media as “a hillbilly Romeo and Juliet.” Then, in 1882, came a vicious attack on Ellison Hatfield, the younger brother of Devil Anse, at the hands of three of Ranel McCoy’s sons in a senseless argument fueled by alcohol and youthful bravado. Ellison was stabbed twenty-six times and shot once; he died two days later. The Hatfields responded by kidnapping the three young men, tying them to pawpaw trees, and shooting them fifty times.

Ranel McCoy considered himself a Christian man who often tried to do the right thing. He wanted to believe that the legal system would protect his family, but again and again, this belief proved unfounded as county officials declined to arrest any member of the Hatfield gang. Ranel’s attempt to secure justice on behalf of his murdered sons led the Hatfield family to strike the final major blow of the feud: in 1888, Devil Anse sent his “Hellhounds” to kill Ranel McCoy in a midnight raid. Instead, they killed two of Ranel’s children (one of whom was crippled from polio), beat his wife nearly to death, and burned down his house.

Devil Anse and Ranel survived the violence and lived into their eighties. But before the feud ended in 1890 with the last public hanging in Kentucky (of a member of the Hatfield family), Ranel had lost seven of his sixteen children. Devil Anse had lost two of his brothers, and five of his sons were in and out of prison for years to come. The Huntington Times in West Virginia summed up the conflict this way: “The famous Hatfield-McCoy feud is at an end. After partaking in the bloody butchery of all the men they could kill, after living as outlaws with prices on their heads, defying arrest and courting meetings with their enemies, after seeing their young men shot down, their old ones murdered, with no good accomplished, they have at last agreed on either side to let the matter rest.”

Devil Anse and Ranel survived the violence and lived into their eighties. But before the feud ended in 1890 with the last public hanging in Kentucky (of a member of the Hatfield family), Ranel had lost seven of his sixteen children. Devil Anse had lost two of his brothers, and five of his sons were in and out of prison for years to come. The Huntington Times in West Virginia summed up the conflict this way: “The famous Hatfield-McCoy feud is at an end. After partaking in the bloody butchery of all the men they could kill, after living as outlaws with prices on their heads, defying arrest and courting meetings with their enemies, after seeing their young men shot down, their old ones murdered, with no good accomplished, they have at last agreed on either side to let the matter rest.”

Alther’s chapter devoted to the feud survivors is especially poignant and clearly shows the human cost of the feud. Although the men got most of the attention in the conflict, women often bore the brunt of their husbands’, sons’, and fathers’ terrible decisions and, like Sarah McCoy, were sometimes themselves the victims of violence. The wives of the feudists were forced to support huge families by themselves after their husbands were wounded, killed, or fled. Mothers watched their children die senselessly and tended the wounded, sometimes for years.

These deaths and broken lives were tragic, but equally disturbing for Alther was the way outsiders began to perceive the residents of the Appalachian Mountains. Newspaper reporters routinely used disparaging adjectives such as “backward, barbarous, dissolute, idle, primitive, revolting, savage, uncivilized, violent, and wild,” she writes. “Between 1905 and 1928 ninety-two silent movies were filmed for national distribution that featured feuding mountaineers exhibiting all those damning qualities and more.”

In this regard, the feud had far-reaching and unexpected consequences for the region. Shortly after the conflict ended, railroad, timber, and coal companies began to buy up the land itself or its resource rights for pennies on the dollar, with devastating results for the vulnerable mountain people. “Because other Americans had come to regard the residents of the southern Appalachians as brutal savages, they felt little concern that those savages were now being starved and maimed, their once sparkling rivers murky with toxins, their towering primeval forests reduced to stumps.”

Blood Feud is an exhaustively researched, well written, and beautifully produced volume complete with maps, endnotes, bibliography, index, dozens of fascinating period photographs, and extensive family trees for the Hatfields and McCoys. Alther, whose own family tree includes ties to the feudists, has created an impressive document that considers not only the events of the feud and their consequences, but the complex web of unique circumstances—historical, geo-political, psychological, educational, spiritual, and socio-economic—that allowed the conflict to begin and to continue for so long.

And yet, Alther notes, the truth of the Hatfields and McCoys may never completely be known: “Like all oral histories, the various versions of the Hatfield-McCoy feud have been embellished, pruned, and honed like rocks roiled to smoothness in a creek bed, by generations of tellers, some creating myths, others righting wrongs, most trying to explain or justify the bad behavior of their ancestors or relatives.” One thing is certain: there was plenty of bad behavior to go around.

Lisa Alther will discuss Blood Feud at Union Ave. Books in Knoxville on June 12 at 6 p.m.