Telling the Truth—with Hospitality

Last month Lipscomb University hosted the Christian Scholars’ Conference, and Chapter 16 has the inside story

It’s a stereotype: Southerners are good at hospitality in part because we are so good at glossing over the truth. As a child growing up in Nashville, one whose church life consisted of Episcopal services on Christmas and Easter, I had a vague sense that our communal friendliness came from living in a place where everyone followed the same rules, especially the one deemed “golden.” But as I grew up, I began to notice that loving thy neighbor as thyself too often hinged on choosing like-minded neighbors—choosing neighbors, in other words, who were already easy to love.

On June 7, Lipscomb University welcomed more than 325 scholars and participants to the thirty-first annual Christian Scholars’ Conference with three days of hospitality and truth-telling centered on the concept of reconciliation, of bridging the gap between neighbors with very different views. A Church of Christ community that’s growing fast and expanding into new disciplines, Lipscomb nonetheless retains strong roots in a religious tradition with a highly sectarian past. In an interview with Chapter 16, David Fleer, director of the CSC, acknowledged “three competing goals that I intend to keep alive and vibrant”: meeting national conference standards in each of the academic disciplines represented at the CSC, interdisciplinary dialogue, and faith as a critical part of the conference experience.

On June 7, Lipscomb University welcomed more than 325 scholars and participants to the thirty-first annual Christian Scholars’ Conference with three days of hospitality and truth-telling centered on the concept of reconciliation, of bridging the gap between neighbors with very different views. A Church of Christ community that’s growing fast and expanding into new disciplines, Lipscomb nonetheless retains strong roots in a religious tradition with a highly sectarian past. In an interview with Chapter 16, David Fleer, director of the CSC, acknowledged “three competing goals that I intend to keep alive and vibrant”: meeting national conference standards in each of the academic disciplines represented at the CSC, interdisciplinary dialogue, and faith as a critical part of the conference experience.

During a performance of Tokens, a radio variety show integrated each year into the theme and experience of the CSC, comedian Greg Lee poked fun at the historical tension between churches and academia. In his monologue, Lee played a self-educated, pulpit-pounding “Brother Preacher” who welcomed the crowd (primarily conference participants with Ph.D. and M.Div. degrees) by saying, “Well, well, well, give a shout, give a holler, looky all the Smarty Pants Scholars! I see English Scholars and Math Scholars and of course my personal favorite, the Bible Scholars! Like I always say: there is nothing like a room full of BS! Amen?” The congregation in the college theater met his call-and-response invitation with a roar of laughter instead, conceding that even academic rigor need not be taken too seriously.

At this year’s conference, there was a friendly seriousness to the people, panels, and surroundings. On my first day, I walked into the atrium of the Ezell Center on Lipscomb’s campus to find it lined by tables with books by conference presenters or published by Church of Christ university presses. As participants gathered, clusters of conversations filled the vaulted space. People greeted each other with pats on the shoulder, one-armed hugs, and occasionally the addition of “Brother” and “Sister” before a name. With its contemporary architecture, rows of hardcover books, and the warm chatter of peers, the Christian Scholars’ Conference brought together in one place a variety of comforts that tend to be unique to such disparate venues as corporate retreats, academic societies, and family reunions.

The conference, which moved to Lipscomb University in 2007, has tripled in size since being adopted by Lipscomb, which hosts it for three of every four years. The growth is likely due to the board’s decision to adopt a broad interdisciplinary theme each year, one that reaches beyond its traditional interests of biblical studies, church history, and theology. During the past five years, the Christian Scholars’ Conference has hosted a number of popular writers and thinkers, including Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Marilynne Robinson, former Poet Laureate Billy Collins, and geneticist and director of the Human Genome Project, Frances Collins. (The headliner this year was to be novelist-physician Abraham Verghese, New York Times bestselling author of Cutting for Stone, but his flight was canceled at the last minute.) The plenary sessions featuring such speakers are always open to the Nashville community without charge and are advertised on WPLN, the local National Public Radio affiliate, as part of Lipscomb’s effort to expose the community to the ideas the CSC engages.

The conference, which moved to Lipscomb University in 2007, has tripled in size since being adopted by Lipscomb, which hosts it for three of every four years. The growth is likely due to the board’s decision to adopt a broad interdisciplinary theme each year, one that reaches beyond its traditional interests of biblical studies, church history, and theology. During the past five years, the Christian Scholars’ Conference has hosted a number of popular writers and thinkers, including Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Marilynne Robinson, former Poet Laureate Billy Collins, and geneticist and director of the Human Genome Project, Frances Collins. (The headliner this year was to be novelist-physician Abraham Verghese, New York Times bestselling author of Cutting for Stone, but his flight was canceled at the last minute.) The plenary sessions featuring such speakers are always open to the Nashville community without charge and are advertised on WPLN, the local National Public Radio affiliate, as part of Lipscomb’s effort to expose the community to the ideas the CSC engages.

This year the theme of the conference was reconciliation, and more than ninety universities were represented by scholars. Although ninety-five percent of those institutions are not affiliated with the Church of Christ, a majority of the scholars and conferees did have some ties to the denomination. In an interview, first-time participant and Vanderbilt Ph.D. student Lauren Smessler-White noted that the importance of the CSC stems from the connections it fosters both within the Church of Christ and with secular organizations. When I asked her about the historic tension between Christian institutions, especially sectarian ones, and secular academia, she described her own view of Christian scholarship as one based on Augustine’s notion that “all truth is God’s truth.”

This broadening of interests and influences follows a larger trend: across the country—election-year politics notwithstanding—evangelical and conservative Christians are moving past the sectarian attitudes of previous generations in search of a more diverse dialog. From her role on the board, Kathy Pulley, a professor of religious studies at Missouri State University, has watched the growth of the conference and its role in the larger cultural dialogue: “This conference is right in the middle of it,” she says. Pulley noted the nationally recognized speakers and the panels addressing “cutting-edge issues in a variety of disciplines” and emphasized that “all are welcome, and the hospitality is great.”

In many of the sessions, there was an assumed familiarity with the particular history and tradition of the Churches of Christ, but if there was a tension between being a “Christian” and being a “scholar” in the five different panel discussions I attended, it was not explicitly expressed. Throughout the conference, questions posed using academic terminology were just as likely to be answered using theological language as academic terms, and theological questions often arose within the scholarly discourse.

In many of the sessions, there was an assumed familiarity with the particular history and tradition of the Churches of Christ, but if there was a tension between being a “Christian” and being a “scholar” in the five different panel discussions I attended, it was not explicitly expressed. Throughout the conference, questions posed using academic terminology were just as likely to be answered using theological language as academic terms, and theological questions often arose within the scholarly discourse.

This year’s plenary-session highlights included Immaculee Ilbighaza, author of Led By Faith: Rising from the Ashes of the Rwandan Genocide. She told her story of survival as a Tsutsi who spent ninety-one days hiding out in a Hutu minister’s bathroom; speaking at the CSC, she discussed her journey to forgiveness of the man who killed her entire family. Also appearing was Miroslav Volf, whom Pulley called “a leading theologian in the world right now.” At the second plenary session, Volf spoke about the circumstances that make religious groups turn to political violence. He drew on his experience of faith-justified violence in the Serbian-Croatian conflict of his home country, Yugoslavia.

In recent years, a consistent strength of the CSC has been the willingness of internationally recognized speakers to remain at the conference and engage in the small-group sessions, and indeed Volf also participated in two panel discussions on Christian-Muslim relations; his latest book, Allah: A Christian Response, challenges listeners not to attempt to reconcile the beliefs of those faiths but to focus on commonality of the people who sincerely practice them.

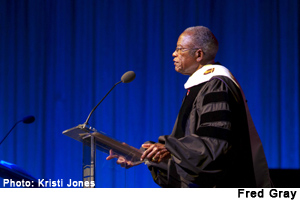

The theme of reconciliation was the most ambitious yet for the Christian Scholars’ Conference, which broke ground this year with the board’s unflinching willingness to turn the truth-telling on itself: Fred D. Gray, a civil-rights activist and lawyer who has represented Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., openly explored the particularities of racism in the Churches of Christ, including a case he filed against Lipscomb itself in 1967. To honor his commitment to justice, Lipscomb’s president, Randy Lowry, conferred on Gray an honorary doctorate of humane letters in recognition of his achievements in civil rights and “for his life-long devotion to destroying everything segregated [he] could find.”

The theme of reconciliation was the most ambitious yet for the Christian Scholars’ Conference, which broke ground this year with the board’s unflinching willingness to turn the truth-telling on itself: Fred D. Gray, a civil-rights activist and lawyer who has represented Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., openly explored the particularities of racism in the Churches of Christ, including a case he filed against Lipscomb itself in 1967. To honor his commitment to justice, Lipscomb’s president, Randy Lowry, conferred on Gray an honorary doctorate of humane letters in recognition of his achievements in civil rights and “for his life-long devotion to destroying everything segregated [he] could find.”

Though relations between the races, and between Christianity and Islam, inspired the most passion and energy at this year’s conference, panels also included gender inequality in the Church of Christ and Christian responses to injustices in the current economic and political climate, particularly those surrounding the rights of immigrants, prisoners, and the uninsured. In his session, Richard T. Hughes, a religion professor at Messiah College, addressed the historic role conservative Christians have played in American politics and took pains to differentiate the historical roots of the Church of Christ fellowship from the “the great Evangelical sucking machine” today, particularly its tendency to claim for itself any conservative Christian institution.

Lee Camp, a professor of theology at Lipscomb, also considered the relationship of Churches of Christ with American Evangelicals in the latter part of the twentieth century: “Churches of Christ have never fit very well within ‘American evangelicalism,’” he said, in part “because of their teaching that Christian discipleship requires the practice of non-violence and the renunciation of war as a means to pursue justice.”

There was standing-room-only at the panel discussion of Camp’s own book, Who Is My Enemy? Questions American Christians Must Face about Islam—and Themselves. The panel included Saeed Khan, lecturer at Wayne State University in Michigan; Amir M. Arain, a physician at Vanderbilt University; and Melissa Snarr, a professor of ethics at Vanderbilt. In her prepared response, Snarr noted the broad audience Camp intends for his book and how “in the culture-war mindset that heavily influences our national and particularly state and local debates, Dr. Camp practices a rich hospitality even in the construction of this book.” According to Snarr, Camp’s strengths as a theologian and writer lie in his ability to invite the reader into an ethical struggle: “While Who is My Enemy? is certainly an important book about the varied approaches of Muslims and Christians to violent conflict, the text seeks first to teach its reader how to listen, learn, and discern.”

There was standing-room-only at the panel discussion of Camp’s own book, Who Is My Enemy? Questions American Christians Must Face about Islam—and Themselves. The panel included Saeed Khan, lecturer at Wayne State University in Michigan; Amir M. Arain, a physician at Vanderbilt University; and Melissa Snarr, a professor of ethics at Vanderbilt. In her prepared response, Snarr noted the broad audience Camp intends for his book and how “in the culture-war mindset that heavily influences our national and particularly state and local debates, Dr. Camp practices a rich hospitality even in the construction of this book.” According to Snarr, Camp’s strengths as a theologian and writer lie in his ability to invite the reader into an ethical struggle: “While Who is My Enemy? is certainly an important book about the varied approaches of Muslims and Christians to violent conflict, the text seeks first to teach its reader how to listen, learn, and discern.”

This year’s Christian Scholars’ Conference made great strides in adding truth-telling to a long tradition of Southern hospitality. The coordinator of the conference, David Fleer, sees Christianity and scholarship as unified in daily life, at least on a campus: “Universities are to be centers for inquiry and deliberation, so a Christian university must be a place of inquiry and deliberation about issues of Christianity. Issues such as war, lack of health care, race, or public policy are part of every Christian’s daily life, and it’s time we started talking about them in an open, honest, and loving way.”