Remembering John

Friends and colleagues recall John Egerton, Nashville’s beloved writer, activist, and mentor

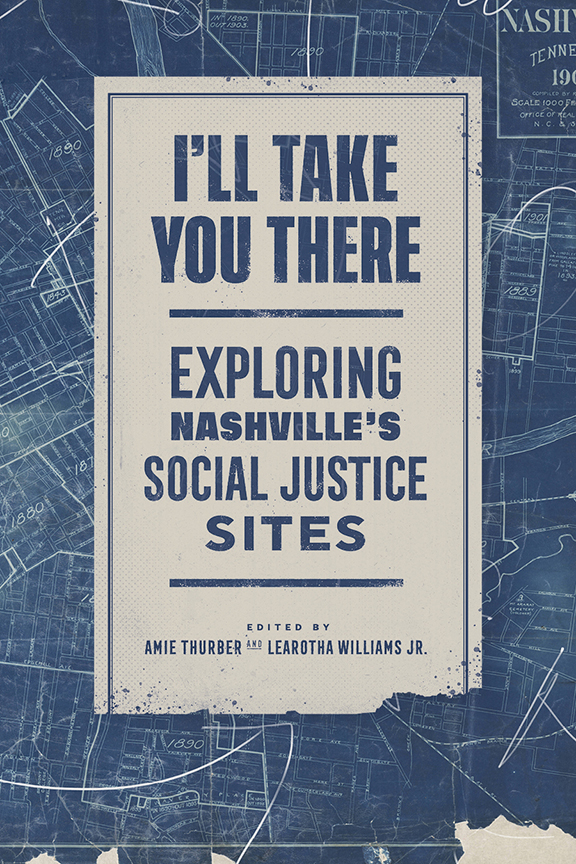

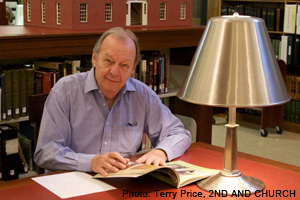

The sudden death of John Egerton—author or editor of seventeen books focused on the cultural life of the American South in all its ugliness and glory—hit us particularly hard: John had been a contributor of essays, reviews, and interviews to Chapter 16, had served as a member of the editorial board since Humanities Tennessee founded the site in 2009, and had long been a mentor and friend. But we are far from alone in mourning the loss of a great writer and advocate for social justice. As soon as news spread of John’s death on November 21 of an apparent heart attack, people who loved and admired him began to share recollections of his lasting impact on the world.

In advance of a public celebration of John Egerton’s life that will be held at the Nashville Public Library on December 8 at 2:30 p.m., we have gathered together some reminiscences from friends and colleagues in Nashville, as well as excerpts from the many obituaries and essays about John in the national media that have appeared during the last two weeks. We’ve concluded with a comprehensive list of John’s books and a brief selection of quotations from John’s recent interviews and speeches—for no one explained John Egerton’s far-reaching ideas better than John Egerton did himself.

Light Years Ahead of His Time

Being in the music business, I hear a lot about mentors. I’ve known some, and I’ve even been called one. (Blake Shelton said I was part mentor and part tormentor.) But I never knew what serious mentoring was until I decided to write a book several years ago, and John Egerton took me under his wing. He became mentor, editor, and encourager-in-chief. And then he became my agent and placed the book with a first-rate publisher. I literally could not have written the book without him, and I went through the same process again with a second book that I recently completed—and, again, I could not have done it without John and his cheerleading.

Being in the music business, I hear a lot about mentors. I’ve known some, and I’ve even been called one. (Blake Shelton said I was part mentor and part tormentor.) But I never knew what serious mentoring was until I decided to write a book several years ago, and John Egerton took me under his wing. He became mentor, editor, and encourager-in-chief. And then he became my agent and placed the book with a first-rate publisher. I literally could not have written the book without him, and I went through the same process again with a second book that I recently completed—and, again, I could not have done it without John and his cheerleading.

I am talking about my close friend. Many people would tell you that he was their close friend, too, and they would be telling you the truth. And all of us were deeply saddened when we learned that this literary giant had died suddenly and unexpectedly at his home in Nashville on November 21.

I guess I shouldn’t be so surprised that John is gone; he was seventy-eight years old. But because he was so vital and his mind so sharp and finely tuned, he didn’t seem old at all, and I just assumed he would be around for a long time. I guess I should know by now that what we want, what we think, and what we plan is never a given. But whether it’s predestined by fate or by God, or just randomly accidental, I don’t have to like it. It will take me a long time to get used to the idea that this wonderful man is no longer around, no longer saying, when something’s not going well, “Damn, son.” Or when something’s going very well, “Damn, son!”

In the early 1960s, back when most Southerners were still segregationists, John was light years ahead of his time, a white, Georgia-born, Kentucky-raised Tennessean crusading for the rights of African-Americans when it was not only uncommon in the South but often dangerous. John Egerton was a brave man, a wise man, a talented man, a modest man, a kind and gentle man, a good man, and, yes, a great man. My condolences go out to his wife and best friend, Ann, his two fine sons and their families, and his countless good friends who will never forget a wonderful human being named John Egerton.

—Bobby Braddock, author of Down in Orburndale: A Songwriter’s Youth in Old Florida

Writing About Our Cowardice and Our Courage

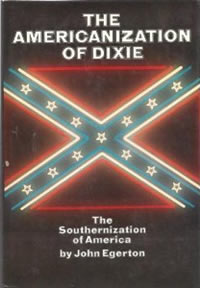

The first time John Egerton and I connected was in 1974 when I interviewed him for A Word On Words, the Nashville Public Television program I host for authors. His book, The Americanization of Dixie, had just been published, and our conversation about his view of the South didn’t end when, after thirty minutes, the camera went blank and the studio lights went out.

“The South is a history without a country,” he once told me. And without a vital voice, now that we have lost his. ~John Seigenthaler

We sat there for an hour in the darkened studio talking about the changes that had taken hold of our home region—some for the better, some not—and how Nashville, my native and his adopted city, had been affected by all that change. He understood, as many do not, that “being Southern” is not some mystical or mythical concept but a way of life to which we are born and escape only through denial, if then.

While John held strong opinions and did not hesitate to air them, he also was a good listener—a gift ordained to make a friend of a big talker, like me. He came back, from time to time, to appear on A Word on Words as his subsequent books were released, and inevitably our on-air program was followed by an on-set, off-camera conversation that gave us a chance to catch up on gossip—in the best Southern tradition.

John was, then, a Southern writer and made no apology for it. Our music, our food, our politics, our literature, our love of story-telling, our cowardice and our courage as it relates to racial history, all were subjects he thought about, read about, talked about, knew about, and, importantly, wrote about.

“The South is a history without a country,” he once told me. And without a vital voice, now that we have lost his.

—John Seigenthaler, founder of the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University and host of A Word on Words.

As If We Were All Exactly His Height

I remember a warm night at Mills’ Bookstore when John Egerton strolled in through the propped-open front door. The century was in its late eighties and I was in my late twenties. Incredibly, John was younger then than I am now. Above the cars idling at the 21st and Acklen stoplight, nighthawks called; I heard the click of billiard balls down the block. John had a way of smiling as he walked toward you—crinkling eyes, a slightly crooked Jimmy Stewart grin. He looked the lowliest clerk in the eye as if he thought we were all exactly his height. While we chatted that night about something he had ordered, my mind changed focus, and I saw his books on the shelves behind him. A writer had climbed out of his author photo and was on his way to becoming my friend. I yearned desperately to write. From my first book review, John spoke to me as a colleague. I wish I had told him that I often peered under the hood of his prose, to figure out how that quiet engine ran so smoothly. I wish I had told him that he was my definition of a gentleman. I wish.

—Michael Sims, author of The Story of Charlotte’s Web: E.B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic

“I Know John Egerton!”

In 1987, Avon N. Williams Jr., then my father-in-law, was suffering from debilitating ALS, which made speech very, very difficult. Each word was a challenge that required a fight for air and a fight to control the muscles of his mouth and throat. It had gotten to the point that the veteran civil-rights lawyer, whose voice had thundered through the Tennessee State Senate, was largely silent. This day, my best friend, Mimi Oka, had come to town, and she mentioned that she was hoping to meet John Egerton. When he heard this request, Avon made the immense effort required to stake a claim. In a voice that was almost as hard to hear as it was to speak, he said, “I know John Egerton!” Then he banged the dining-room table with his fist. He remembered John’s phone number, so I called. Thus began a friendship between John and a black woman young enough to be his daughter that would span a quarter century. And when Avon died in 1994, John Egerton gave his eulogy in the Tennessee State Capitol.

Often when I encountered a perplexing racist slight it was John I called, and John usually healed it with a story. My daughter was once excluded from a close friend’s birthday party because the party was in Beersheba Springs, an exclusive resort in Grundy County, and my daughter’s friend told her that a black child would not be welcome there. I called John to help me figure out what I should do. John told me the story of the progressive Highlander Folk School, originally located in Grundy County. “We Shall Overcome” was written at Highlander, and many leaders of the civil-rights movement were trained there. When my daughter went back to school and told her tales of Grundy County, the place had been stripped of its capacity to shame her.

Often when I encountered a perplexing racist slight it was John I called, and John usually healed it with a story. My daughter was once excluded from a close friend’s birthday party because the party was in Beersheba Springs, an exclusive resort in Grundy County, and my daughter’s friend told her that a black child would not be welcome there. I called John to help me figure out what I should do. John told me the story of the progressive Highlander Folk School, originally located in Grundy County. “We Shall Overcome” was written at Highlander, and many leaders of the civil-rights movement were trained there. When my daughter went back to school and told her tales of Grundy County, the place had been stripped of its capacity to shame her.

There wasn’t an inch or an acre of the South that John didn’t know something good about. He always used his knowledge of the good to make it possible to stare unblinking at the bad as he did his level best to dismantle it.

And he took time to mentor young writers. It was John who pushed me toward writing a cookbook memoir, John who brainstormed its structure with me one day in a parking lot. John often said, “I’m so proud of you,” and he was saying it for Avon and for my daddy. That’s the kind of service white men of John’s era rarely performed for black men. John was a tender kind of rare.

He was the best of us. For seeing and telling the South without fiction he had no peer. I would not be the writer, the cook, the person I am without him, and that is the cry of so many of us. I love you, John. This is my simple, solemn sigh.

—Alice Randall, author of Ada’s Rules

Writing to See What He Could Learn

John was a magnificent writer, a wise and wonderful friend, and someone my wife Martha and I were always glad to see. He was so generous in support of other writers—not just with advice but by buying their books. He was an enthusiastic advocate for many book-related activities, such as the Southern Festival of Books, where we had a long conversation with him.

I interviewed him at length on three occasions, and two memories from 1987 stand out. When he had decided on life as a freelance writer, he said, the best advice he received was “Hang on to your day job.” He ignored it and didn’t regret that he had. “Writing is a disease and an affliction,” he said, and if you must, “persevere and do what you have to do.” The other memory was how he decided on subjects for his books. His approach was “Here’s a subject I’m interested in. I think I’ll write about it and see what I can learn.” He told me that he “knew practically nothing” about food when he started research and writing for Southern Food.

John’s was a well-lived life, not just as a writer but as part of the human community.

—Roger Bishop, founding editor of BookPage

An Honor To Have Him As a Friend

I met John at the meetings the Nashville Public Library sponsored to try to uncover someone who would open a bookstore after the closing of Davis-Kidd. He was so supportive when he found out that Ann Patchett and I were the ones who decided to pursue the idea. I remember a lovely lunch that I had with him and Michael Zibart to discuss the ideas we had for the store. It really brightened my day when I would see him in the store. It was an honor to have him as a friend and supporter of the store.

—Karen Hayes, co-owner of Parnassus Books

Talking to John Egerton, the World Always Got Bigger

The first time I met John Egerton, years ago, was around the time he wrote A Mind to Stay Here. That book had a big influence on me, a young newspaper reporter soon to be out of college, wondering where to live and work next. I remember feeling that John’s first book spoke directly to me: those tales, all true, of notable Southerners who had not moved away.

The last time I saw John was just three weeks ago, in Aisle 14 (Chips, Nuts, Trash Bags) at the Green Hills Kroger. I turned around, and here he comes, like he had come all the way over there just to find me. John had helped me with my own book, and—as often happened with John—this chance meeting turned into one more mentoring session. John never failed to ask what projects I had going, how my book was progressing, what other writing ideas I’d had lately.

The last time I saw John was just three weeks ago, in Aisle 14 (Chips, Nuts, Trash Bags) at the Green Hills Kroger. I turned around, and here he comes, like he had come all the way over there just to find me. John had helped me with my own book, and—as often happened with John—this chance meeting turned into one more mentoring session. John never failed to ask what projects I had going, how my book was progressing, what other writing ideas I’d had lately.

Talking to John Egerton, the world always got bigger. John was always encouraging me in that drawl of his and with that excited look on his face, the look of both hope and fellow-suffering. When John answered a question, he looked you directly in the eye, with this knack he had of shutting out all the world but you. He always nodded appreciatively, and he never walked away, not until the conversation came to its natural end. He was always encouraging.

That voice and that look, I know, were the same voice and the same look that he used when he mentored a thousand others, and John was very good at this mentoring business. Some of the last help he gave me was over the phone, maybe eight weeks ago, about a new idea I had for my next book. John warmed up to it quickly—suggested people to interview, angles to think about. With John, it was not just about getting the story: it was also about truth and honesty, about salvation and redemption, and how the long march and hard work were worth it in the end. He might have helped you salvage that piece of writing that was giving you fits. But, later, you also felt he was somehow saving your soul.

—Keel Hunt, author of Coup: The Day the Democrats Ousted Their Governor, Put Republican Lamar Alexander in Office Early, and Stopped a Pardon Scandal

He Earned it All

I was nervous when I first met John. He was the potential editor for a project Nancy Rhoda and I had begun for The Land Trust for Tennessee, and all I knew of him was his bio. Here was a highly respected thinker and writer of the American South with an impressive, not to mention intimidating, roster of books to his name. Why would he want to tackle the job of editing this book when he could easily have written it himself, and done a far better job of it?

The answer, I think, had something to do with John’s belief in the importance of stories and something to do with his belief in the importance of preserving natural spaces in his adopted home state of Tennessee. John first signed onto our project out of love for Nancy, a dear friend from their days at The Tennessean, but he soon became invested in the families portrayed in the book. And, I felt, he was doing it for me, too, serving as a mentor while I was writing my first book.

Most people don’t know that John spent three of the last four years of his life highly involved in this project, a book which came to be called Home To Us: Six Stories of Saving the Land. People don’t know this because he undertook the work wholly voluntarily, without compensation or recognition of any kind. The man I met that first day was hardly the imposing figure I had conjured in my mind. He was warm. And gentle. He listened and he talked, kindly. There was no off-putting intensity or ego from him; there was only a twinkle-eyed, earnest interest in us and our project. It was John’s rare combination of wisdom and humor that helped pull our team, and our book, together.

Most people don’t know that John spent three of the last four years of his life highly involved in this project, a book which came to be called Home To Us: Six Stories of Saving the Land. People don’t know this because he undertook the work wholly voluntarily, without compensation or recognition of any kind. The man I met that first day was hardly the imposing figure I had conjured in my mind. He was warm. And gentle. He listened and he talked, kindly. There was no off-putting intensity or ego from him; there was only a twinkle-eyed, earnest interest in us and our project. It was John’s rare combination of wisdom and humor that helped pull our team, and our book, together.

John would not like all this fussing over him—all these tributes, all this press—but he earned it all. He was indeed a pioneer thinker and writer. But to us at the Land Trust for Tennessee he was a friend, the most devoted, self-effacing kind: the one you want at your dinner table, the one you call when you run into trouble, the one who makes you feel you matter.

—Varina Willse, author of Home to Us: Six Stories of Saving the Land

In the Presence of Greatness

We have lost a great writer and a great human being with the passing of John Egerton, a gentle yet ferocious force for good in our world. John was one of the first people I met when I moved to Nashville in the late 1980s, and I treasured my friendship with this remarkable man. He immediately made me feel welcome in Nashville and always treated me as a peer, though of course I knew that I was in the presence of greatness when I had the opportunity to spend time with John. This Thanksgiving, my family and I gave thanks for John’s life while enjoying his recipe for iced tea and passing around copious baskets of cornbread and other fine Southern fare in his honor. I will always be grateful for John’s significant contributions in making our world a better place for all and for his many kindnesses toward me.

—Mona Frederick, Executive Director of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities at Vanderbilt University

Crediting the Little-Known

UNC Press was fortunate to be the publisher of the paperback versions of two of John Egerton’s best-known works, Southern Food and Speak Now Against the Day (both originally published by Knopf), which dealt with, respectively, food and the early civil-rights movement. The two topics would seem to have little in common, but both books reflect John’s interest in naming and crediting relatively little-known people who made outsized contributions to what we now recognize as the best elements of Southern society. His life and work are a reminder to us of the difference one committed person can make. We are immensely proud of our long relationship with him.

—David Perry, editor-in-chief, retired, University of North Carolina Press

“What Are You Working On?”

John belonged to a large circle of writer-friends. When I was food writer for the daily newspaper, he shared his sources, suggested stories, and always asked, “What are you working on?” His company was a pleasure, occasionally curmudgeonly, and his conversation engaging. He was not afraid of a little bourbon. John gave me several gifts I’ll never forget. His recipe for fudge. A Trigg County ham from his secret source, plus his recipe for crumb coating. His three collections of family recipes, titled Lovin’ Spoonfuls. I will always regret that I didn’t drop by more often when I passed his house. I still had so much I wanted to discuss with him.

—Nicki Pendleton Wood, author of Nashville: Yesterday and Today

Keeping a Hard Stare at Injustice

I was born with two big brothers. A few days ago, walking toward lunch with John’s hand on my shoulder, I had three. Our talk, always just above a whisper, our old ears pointed toward each other’s words. Words brought us together in the first place, and the joy of friendship, a prayerful life, and helping others in our own backyards: me, a recovering agnostic, John, a self-proclaimed back-sliding Unitarian. What outing could be more holy?

But John, I’d say, you only left us yesterday. ~Bill Brown

John appeared in a side chair at my last three readings—to honor a friend and ask a question during the Q&A that no one could answer. He spent much of his life asking the most important questions, keeping a hard stare at injustice. A rare few stroll this earth with such honest grace, kindness, and concern for others, stroll this earth with a shining brilliance that doesn’t call attention to itself. This is how I will always remember my adopted brother, a man who would walk a mile to taste new barbeque, an aficionado of cornbread and black-eyed peas, the only journalist to interview James Earl Ray, a hero in a world short on heroes, a writer who would find this eulogy too sentimental. But John, I’d say, you only left us yesterday.

—Bill Brown, author of The News Inside

Excerpts from National Media Coverage of John Egerton’s Life

“John Egerton, the Nashville writer who authored a definitive book on Southern food and history, used to tell a tale on me: he said that when I first visited his office back in 1996, he caught me casing the joint. The way he told it, he returned from the bathroom to find me running my fingers down the spines of his books, riffling through his files, making his ideas my own.” ~from “Remembering Egerton, Who Knew the Power of the Southern Table” by John T. Edge, writing in The New York Times

“Mr. Egerton rambled across the South, sampling hush puppies, grits, black-eyed peas, fried chicken, and barbecue in all its savory permutations. Southern Food was not a cookbook, not a history, and not quite a travelogue. It was an utterly original cultural study that made Mr. Egerton nothing less than a folk hero to people who loved the varied cuisines of the South.” ~from an obituary in The Washington Post by Matt Schudel

“Mr. Egerton rambled across the South, sampling hush puppies, grits, black-eyed peas, fried chicken, and barbecue in all its savory permutations. Southern Food was not a cookbook, not a history, and not quite a travelogue. It was an utterly original cultural study that made Mr. Egerton nothing less than a folk hero to people who loved the varied cuisines of the South.” ~from an obituary in The Washington Post by Matt Schudel

“If John Egerton liked you—and he liked nearly everyone he met—he might have hauled out an antique contraption called a biscuit brake, whipped up a batch of special unleavened dough, and cajoled you into cranking the device while he related the story behind beaten biscuits, an old Southern favorite. He would tell you that in the pre-mechanical days the dough would be beaten with a mallet or even the side of an ax—an arduous task left to slave cooks in wealthy antebellum households. After the brake was invented, it did the hard work, saving beaten biscuits from extinction. This exercise was, for Egerton, not only about good eating: It was a form of communion with the South’s thorny past.” ~from an obituary in The Los Angeles Times by Elaine Woo

“John Egerton understood that the American South was a region of contradictions, holding both savagery and sweetness, churchgoers and evildoers, good cooking and bad. ‘There is no explaining,’ he once said, ‘how the best writers would come from the region that has the most illiterates.’” ~from an obituary in The New York Times by Kim Severson

“Nashville bids farewell to Egerton, whose death came swiftly after a heart attack at the age of 78. Born in Georgia and raised in Kentucky, Egerton was a Southern boy—top to bottom. His sweet, slow, John Boy Walton-flavored drawl was hypnotic and had a disarming effect on even the most aggressive power-talking Yankee.” ~from “John Egerton Revealed South’s Cultural Roots” by Molly Secours, writing in The Tennessean

“For my wife Nathalie Dupree and me, our lasting memory of this year’s Southern Book Festival in Nashville is our having lunch on Saturday with John Egerton at one of his downtown hideaways. It marked the twentieth anniversary of my first meeting Nathalie, at the October 1993 festival. We got married six months to the day later.” ~from “My Friend John Egerton” by Jack Bass, writing in the Charleston City Paper

“John’s most popular writing celebrated what was good about the South, but his biggest contribution as a journalist and historian was his examination of what held the region back: race, class, poverty, inequity and corruption. He was a masterful storyteller who had the courage to not only report facts, but explain what those facts added up to.” ~from “Paying Tribute to John Egerton” by Tom Eblen, writing in the Lexington Herald-Leader

“John’s most popular writing celebrated what was good about the South, but his biggest contribution as a journalist and historian was his examination of what held the region back: race, class, poverty, inequity and corruption. He was a masterful storyteller who had the courage to not only report facts, but explain what those facts added up to.” ~from “Paying Tribute to John Egerton” by Tom Eblen, writing in the Lexington Herald-Leader

“John Walden Egerton was a noted chronicler of the South for his nearly half-century as a journalist and author. He shared everything about his homeland, from the delight he savored in its cuisine to his disdain of the cultural injustice too many endured.” ~from an obituary in The Dallas Morning News by Joe Simnacher

“He was championed as the ‘culinary mouth of the South’ and described as a ‘Southern Homer’ who chronicled the region’s saga as it ‘passed orally from plate to plate.’ A Courier-Journal food critic wrote once that one ‘loving mention’ from him was worth ‘five stars in any restaurant guide.’” ~from an obituary in the Louisville Courier-Journal by Andrew Wolfson

“Just as John Egerton would not let denizens of the present forget the past, he will not soon be forgotten by those that share his love of Southern culture. His fervent attention to the importance of preserving the history of the region will be reflected on menus, in hearts and minds for a long time.” ~from an obituary in Food Republic by Chris Chamberlain

“Mr. Egerton—something I could never help but call him, though with mild consternation he would always correct me with ‘John’—was a man of great passion, despite his soft-spoken demeanor. On issues where the South was lagging in progress, from civil rights to poverty, he was dauntless and unwavering, whether he was tackling the problem of ‘food deserts’ in impoverished communities or charting the early fight against segregation in his landmark 1994 book Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South.” ~from an obituary in the Nashville Scene by Jim Ridley

“One of John’s lasting contributions to understanding the South was his book, Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South, published in 1994. More than any other of his many works, this title, taken from William Faulkner, was the one John really cherished. For it captures John’s own motto of life and his enduring hope for the region he loved—to have everyone in the South ready with the courage, persistence, and devotion to speak truth to and about those who are powerful, hateful, or in the moment’s ruling majority on behalf of those human values that always placed John and his voice on the right side of Southern history and now places him among the angels.” ~from a recollection by Steve Suitts

“Friends and family recalled him as a writer who tried to find and understand the stories of uncelebrated Southerners, those whose names never appeared in history textbooks and whose traditions often were ignored. A traditional Christmas spread inspired Egerton to think of the African-American cook who labored in the kitchen. A trip on the road would include a meal at a greasy-spoon that had defied Jim Crow by serving blacks and whites alike.” ~from an obituary in The Tennessean by Chas Sisk

“Friends and family recalled him as a writer who tried to find and understand the stories of uncelebrated Southerners, those whose names never appeared in history textbooks and whose traditions often were ignored. A traditional Christmas spread inspired Egerton to think of the African-American cook who labored in the kitchen. A trip on the road would include a meal at a greasy-spoon that had defied Jim Crow by serving blacks and whites alike.” ~from an obituary in The Tennessean by Chas Sisk

“His work was transformative. He was both a traditionalist and a progressive, a man with great vision for social justice. He was clear that there was no point in creating an organization like [the Southern Foodways Alliance] to mythologize or dance around the edges. The people’s food was John’s food. He was very supportive of young chefs who worked hard to uphold the core traditions of simple home cooking and the meat-and-three cafes.” ~from a recollection by author Marcie Cohen Ferris

“Throughout the changes that Egerton witnessed and documented in the South, he kept an impenetrable devotion to his home and the people that made this region home for him. In Southern Food, you can still feel his fondness for the prototypical Southern dinner. ‘When the chemistry is right, a meal in the South can still be an esthetic wonder, a sensory delight, even a mystical experience,’ Egerton wrote.” ~from an obituary in the Jackson Free Press by Justin Hosemann

John Egerton in His Own Words

“When I realized how much Southern food meant to me and meant to the people who wanted the South to have a more rounded image than just the violence and the racism, I began to realize that food is the great communications medium. It’s the great binder that brings us together as a people.” ~from a video tribute to John Egerton by the Southern Foodways Alliance

“Be wary of your machines. Save some paper, some pens, ink, and erasers. Don’t forget how to put your thoughts fearlessly into words on paper. And if the power fails, you’ll still be able to read and write.” ~from a 2012 speech at Frist Center for the Visual Arts

“English is getting trashed in the digital age, both literally and figuratively. Grammar, spelling, punctuation are being mauled by the so-called social media. Our native language (which probably should be called American instead of English, so thoroughly has it been transformed from the original, and for the better) is going the way of legible penmanship—printed/keyboarded/tweeted/texted into something altogether different from the English we took for granted. No wonder the English major is almost extinct. Maybe this will run its course and there will be a rebirth of the form and content of English, but I doubt it. More likely, we ‘old hands’ will be the ones compelled to adapt. In my humble opinion, though, one thing won’t change: There will always be a critical mass who will yield to the compulsion to write, and they will always produce more than enough words to meet the needs of the communications industry. Never in human history has it been necessary to ration words. Writers have always been—and will always be—more than equal to the task of keeping humanity in ample and overflowing abundance, regardless of the demands of the media.” ~from an interview in 2nd & Church

“In the best and worst of times, a tiny fraction of the population will always aspire to tell their stories; a minute number of writers will actually follow through and complete manuscripts; a mere handful of those in-vitro books will go on to have their own lasting identity; and a small remnant of the surviving volumes, whether printed and bound or digitized and flat-screened, will have enough of a healthy history to be remembered as something more than a flash of light and a puff of smoke.” ~from an essay by John Egerton for Chapter 16

Books by John Egerton

—A Mind to Stay Here: Profiles from the South, photographed by Al Clayton (1970)

—Promise of Progress: Memphis School Desegregation, 1972-1973 (1973)

—The Americanization of Dixie: The Southernization of America (1974)

—Visions of Utopia: Nashoba, Rugby, Ruskin, and the “New Communities” in Tennessee’s Past (1977)

—Education and Desegregation in Eight Schools (1977)

—Generations: An American Family (1983)

—Radnor Lake: Nashville’s Walden, photographed by John Netherton (1984)

—Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, In History, photographed by Al Clayton (1987)

—South (1987), photographed by Bill Weems

—Side Orders: Small Helpings of Southern Cookery & Culture (1990)

—Shades of Gray: Dispatches from the Modern South (1991)

—Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (1994)

—Ali Dubyiah and the Forty Thieves: A Contemporary Fable (2006)

Books Edited by John Egerton

—Nashville: The Faces of Two Centuries, 1780-1980 (1979)

—Nashville: An American Self Portrait, edited by John Egerton and E. Thomas Wood (2001)

—Cornbread Nation 1: The Best of Southern Food Writing (2002)

—Home to Us: Six Stories of Saving the Land by Varina Willse (2013)

A public celebration of John Egerton’s life will be held at the Nashville Public Library on December 8, 2013, at 2:30 p.m. Click here for event details. Click here for a remembrance of John’s irreplaceable role at Chapter 16.