Switching Sides

Glenn Feldman explains how the once-blue South turned red

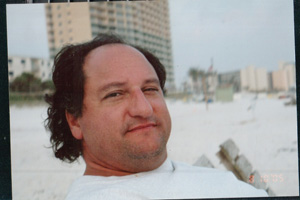

“The South began its move toward the modern Republican party in 1865,” writes Glenn Feldman in the opening sentence of his new book, The Irony of the Solid South: Democrats, Republicans, and Race, 1865-1944. He spends the next 450 pages backing up this surprising statement with overwhelming historical evidence. Feldman is a professor of history at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where he has also been a professor of economics and the director of the Center for Labor Education and Research. Among his five degrees is a master’s in political science, which he earned in 1986 at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, where he was a university fellow. He recently answered questions about the book, and current events which seem to bear out his thesis, via email.

Chapter 16: On June 25, 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned key provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on the grounds that the conditions of disenfranchisement forming the basis of the law no longer existed. Within twenty-four hours, five Southern states began imposing new voting restrictions. The Irony of the Solid South presents a solid case that Southern opposition to the Voting Rights Act, and to subsequent similar legislation crafted by Democrats, remains firmly rooted in 1865. To what degree did efforts to insure fair voting practices drive the South toward the Republican party?

Glenn Feldman: Federal efforts to insure fair voting practices along racial lines were—along with federal efforts at desegregation and civil rights—probably the most important factor in causing the South to become Republican. As these federal efforts were clearly identified with national Democratic leaders such as Harry Truman, John and Bobby Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic Party in the South paid the price by gradually—but powerfully and directly—seeing its white conservative base look for various alternatives.

Glenn Feldman: Federal efforts to insure fair voting practices along racial lines were—along with federal efforts at desegregation and civil rights—probably the most important factor in causing the South to become Republican. As these federal efforts were clearly identified with national Democratic leaders such as Harry Truman, John and Bobby Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic Party in the South paid the price by gradually—but powerfully and directly—seeing its white conservative base look for various alternatives.

Actually, prior to these developments, the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt clearly alienated white Southerners in direct proportion to the New Deal’s inclusion of black people in its programs and FDR’s focus on reform (from 1935 on) instead of simply relief and recovery (1933-35). The alternatives to continued fealty to the Democratic Party that white Southerners experimented with included the Dixiecrats of 1948 and beyond, George Wallace-style independentism, and, finally, conversion to the GOP—a conversion accelerated and cemented by the entry of the Religious Right into politics and the rise of the Reagan-Bush era.

Chapter 16: Are the recent voter ID laws direct descendants of the poll taxes and literacy tests of the last century?

Feldman: Is there a philosophical kinship between today’s Voter ID laws and yesterday’s poll taxes, literacy tests, and other mechanisms of disfranchisement, the answer is clearly and sadly yes. Far too many conservative and Republican operatives have been caught—many proudly—espousing the virtues of shrinking the electorate by any means possible. In fact, I write in depth in the book about two “Great Meldings” that made possible the modern Republicanization of the South. The first involved the conservative appropriation of the white-supremacy issue away from economic progressives by cleverly fusing the holy grail of white supremacy with economic conservatism (even a form of hyper-libertarianism) along the shared and irresistible basis of hatred and fear of the federal government.

The Second Great Melding, which has really accelerated the Republicanization of the South in recent decades, has been the joining of economic fundamentalism to religious fundamentalism in the South by fusing the two with the common adhesive of their well-known and easily documented aversion to democracy and voting by those that are “unfit” to do so—either by their lowly economic status or the “immorality” of their religious and moral views—often, not inconsequentially, connected to their skin color.

Chapter 16: In the book’s preface, you write that in the aftermath of the Depression and the New Deal, “White southerners didn’t so much become Republicans so much as they stopped being Democrats.” What are some of the Southern cultural attributes that led to this political break-up, and to what degree do those attributes continue to drive Southern political behavior today?

Feldman: I speak in the book about a “Reconstruction Syndrome” and the calcification of conservative culture in the South, as well as the phenomenon of the creation of something that may be called “The Southern Religion” that far supersedes simply religious or theological matters. Put simply, history “happened” to the South in a way that it never has happened to the rest of the country, which is one of the primary bases of the region’s continuing distinctiveness.

Feldman: I speak in the book about a “Reconstruction Syndrome” and the calcification of conservative culture in the South, as well as the phenomenon of the creation of something that may be called “The Southern Religion” that far supersedes simply religious or theological matters. Put simply, history “happened” to the South in a way that it never has happened to the rest of the country, which is one of the primary bases of the region’s continuing distinctiveness.

The “history happened to the South theme” is an old one, popularized by the great C. Vann Woodward. The “Reconstruction Syndrome” is not. It has to deal with a set of distinct characteristics that were burned into the collective and predominant Southern consciousness by the military, social, cultural, economic, and especially psychological trauma of Reconstruction. Military defeat and occupation by a “foreign” power is something that has never happened to any other place in America besides the South. The psychological trauma was so severe—as was witnessing the freeing, granting of civil rights to, and enfranchising of the former slaves—that the whole experience left the South with a set of powerful and distinctly illiberal attitudes: a visceral hatred and fear of all things federal, of taxation, a deep suspicion of public education and learning as a nursery for social and racial convulsion, a resentment of “programs” for the poor and people of color, a burning desire to restrict and control suffrage to only the “deserving” and suitable, an affection for government retrenchment and austerity, strict adherence to keeping people in “place” as a way to preserve social order, a devout regional xenophobia and suspicion of outsiders, especially “outside agitators,” among other traits.

Obviously, there are exceptions. The important point to remember, though, is that, on the whole these are truisms of the region and its peculiar historical development—and remain so. History and politics, even economics, are humanistic forms of inquiry. They differ fundamentally from those of the hard sciences in a variety of ways—subject matter, evidence, method, the effect of researcher bias, etc. In humanistic inquiry the finding of exceptions to the rule may (and in the Southern case, do) actually strengthen the rule due to the very exotic nature or the rareness of the exception. Not so in the hard sciences: one apple refuses to fall to the ground after it drops from a tree and the law of gravity is in serious peril.

Sure, you can find white, Southern-born and bred, racial and economic liberals, who are open-minded, not hostile to the federal government, not Calvinistic in their take on religion and poverty and economics, not averse to governmental solutions to society’s problems, not reflexively hyper-nationalistic to the point of jingoism. But are these individuals the rule in the South? Have they been throughout Southern history? Are they today? To ask the question is to answer it.

As long as the Democratic Party was the “Democratic and Conservative Party” in the South (its formal name), Dixie could profess allegiance to it. When that changed, as it did beginning mostly in 1935, white Southerners began to look for alternatives, an odyssey that eventually led to the modern Republican Party—a party which has allowed itself, as a result, to be Southernized and made more extreme with each passing election cycle.

Chapter 16: You present several examples of Southern opposition to federal programs that actually would have benefitted Southern citizens. The fact that states like Alabama and Mississippi have opted out of federally-funded Medicaid expansion, for example, seems to support your assertion that “whites of modest means repeatedly act to their material detriment.” Republican legislators argue that they’re rejecting millions in federal aid in order to help balance the federal budget. I’m guessing you have another explanation for such decisions?

Feldman: Obviously, the lion’s share has to do with what we have already discussed in terms of a “Reconstruction Syndrome,” “The Southern Religion,” and the like. Such Quixotic posturing also allows these politicians to pose as the guardians and heroes of Southern culture even at the expense of money. You see, there are things more important than money: honor, pride, principles, blah, blah, blah.

George Wallace made a career out of doing exactly the same thing—being an expert at continuing the anti-New Deal right’s orchestrated, well-funded, choreographed, and propaganda-driven project to convert the federal government in the public mind from something that helped people (as it had been generally conceived, especially in the early part of FDR’s tenure) into the Big Gov’mint Devil. And it’s worth mentioning that before his death, George Wallace regarded himself as a Republican and jokingly said that he should have demanded royalties for his speeches and ideas so that the modern GOP would have paid him millions. Dan Carter’s work is indispensable in understanding the critical role of Wallace.

What we have here is an historic shift of American suspicion of concentrated power away from large corporations and to the government—the government as the source of all our problems, except when it builds roads and highways, airports, train stations, ports, parks, libraries, sidewalks, hospitals, and maintains a national defense, emergency personnel and agencies, beaches, national parks and forests, Medicare, Social Security, lower-interest student loans and grants, or hands out hurricane- or tornado-relief checks. It’s always the enemy … except then.

Chapter 16: You write that “the more it was pushed on race, the more the South began to view itself as not only a separate culture but, in fact, a separate nation, for all intents and purposes.” How does that nation manifest itself today?

Feldman: In a hundred ways, some of them good. The South (and the work of sociologists like John Shelton Reed and journalists like W. J. Cash have long documented this) is more religious, more courteous, more conservative, more hospitable, more humid, more patriotic, hotter, more violent, and on and on relative to other parts of the country. There is an undeniable regional cohesiveness that anyone who has left the Atlanta airport, or visited someplace in the South besides Disney World, or actually gotten off an interstate and traveled some Southern back roads knows about—intuitively, viscerally, unmistakably.

It’s not all bad. Far from it. Look at Coca-Cola, Chick-Fil-A, Krispy Kreme, NASCAR, the “other religion” of college football, and country music (especially the classic country of Kristofferson, Cash, Willie Nelson, and Patsy Cline). Or the rich tradition of Southern literature from Faulkner to Warren to Welty to O’Connor to the present. These things are not, in and of themselves, intrinsically bad.

But back to your question: at precisely those junctures when the South perceived itself as having its back pushed up against the wall (particularly by the federal government), the “nation within a nation” concept first pointed out by W. J. Cash is most visible. In recent decades—particularly after passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965—other issues (God, guns, and gays, prayer in schools, proper patriotism in the face of terror, abortion, and the like) have all been tapped into by shrewd political advisors from Harry Dent to Lee Atwater to Karl Rove to help the conservative white South feel vulnerable, fearful, under siege, and to act accordingly at the polls—even if voting for a “Christian,” homophobic, and death-penalty-loving GOP brought with it an economic program decidedly detrimental to the interests of working- and middle-class whites.