Giving Gifts to Keep As Long as You Live

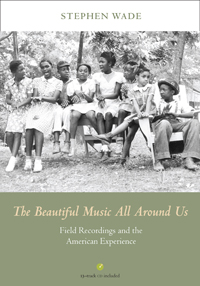

Stephen Wade discusses the stories behind the classic folk recordings in his book, The Beautiful Music All Around Us

In The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience, author and musician Stephen Wade writes of his eighteen-year journey to discover the stories behind several classic American folk tunes and the lives of the people who brought them to life. The book focuses on thirteen Library of Congress field recordings made between 1934 and 1942. Recorded on front porches, in kitchens, prison yards, and churches, these classic components of the American musical landscape were captured by researchers who were more interested in the songs themselves than the performers.

Seeking to complete the chronicle, Wade tracked down the families and associates of these often “ordinary” people. The resulting stories combine cultural archeology and classic detective narrative to demonstrate how human lives intersected with American cultural traditions: these brief moments behind a microphone left a powerful legacy. Wade recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Seeking to complete the chronicle, Wade tracked down the families and associates of these often “ordinary” people. The resulting stories combine cultural archeology and classic detective narrative to demonstrate how human lives intersected with American cultural traditions: these brief moments behind a microphone left a powerful legacy. Wade recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: I was particularly impressed by the way your profiles go beyond just biographical information and instead chart the course of both the song and the performer, following the two narratives to the intersection of the field recording and then on to the legacy of that particular performance. What challenges did you encounter by setting your scope so wide?

Stephen Wade: This twining of the individual and social tradition characterizes all the performances featured in the book. The original editors of these releases—first published on albums in the early 1940s—likewise saw their selections as both exceptional and representative. It’s by that light, too, that I first became exposed to these recordings. My banjo teacher, Fleming Brown, who sent me off to listen to them when I was a teenager, emphasized that distinctiveness, that fusion of the personal and the historical. So, in coming back to them via the medium of this book, that indivisibility of the song and performer seemed inescapable as well as characteristic of this artistry.

Stephen Wade: This twining of the individual and social tradition characterizes all the performances featured in the book. The original editors of these releases—first published on albums in the early 1940s—likewise saw their selections as both exceptional and representative. It’s by that light, too, that I first became exposed to these recordings. My banjo teacher, Fleming Brown, who sent me off to listen to them when I was a teenager, emphasized that distinctiveness, that fusion of the personal and the historical. So, in coming back to them via the medium of this book, that indivisibility of the song and performer seemed inescapable as well as characteristic of this artistry.

The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience grows out of song studies, a craft I tried to learn from another remarkable teacher, folklorist Archie Green. Archie, like Fleming, knew that the recordings he investigated rested on complex foundations. His dazzling body of work, built from an extraordinary network of correspondents and resources, repeatedly explores the interplay of inherited tradition and the performer’s social surround. He saw folksongs and allied forms of vernacular expression as arising within larger political and ideological currents, changing in their meanings as they moved from one set of singers to another. Naturally, the example he provided affected my own studies.

These are field recordings, and the audible presence of life that inhabits them—kitchen clocks ticking in the background, trucks driving by, roosters crowing, neighbors commenting—underline the connection of art and life they audibly capture. So, in relation to your question, I sought out the stories of these players’ lives, as well as their songs, exploring their settings both musically and socially, and their legacies in the years since the initial recordings were made.

As a framework, I tried to listen to whatever commercial and field recordings of these pieces existed in addition to reading whatever I could about them, sheet music included. While the final product does not parse all those precedents and outcroppings, I just felt I owed it to the readers to know that body of work as fully as I could. To do that also helped me feel in some command of the material. I recognize that even with these measures, there’s always more to learn. Sometimes information gets lost, and vital clues have vanished. If nothing else, I kept after each chapter, pursued each study, and wrote each essay until I felt I reached its critical mass, finding whatever its story might tell. At heart, too, people like to read about people. So the book weaves itself around these individuals and their extraordinary performances, uniting, as Yeats writes, the dancer with the dance.

Chapter 16: These recordings represent a tremendous diversity of ages, backgrounds and types of people. Are there any common threads or themes that you see tying their stories together?

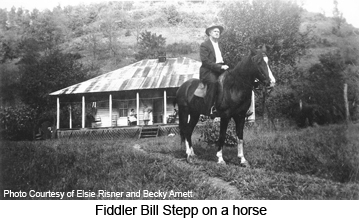

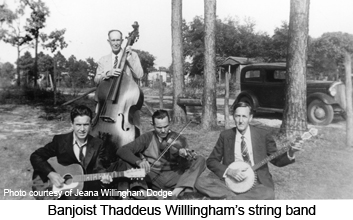

Wade: Sometimes when I imagine the book, I can almost hear all the tracks at once. As you know, there’s a CD included with the book, and in those moments it’s as if that whole orchestra of utterances and sounds, histories and images, contacts and miles, fleets across this gamut of voices, one number stacked upon the next. The music spans all sorts of categories: young/old, black/white, male/female, solo/ensemble, sacred/secular, urban/rural, instrumental/unaccompanied, occupational/recreational, and so on. Similarly, these recordings took place in widely divergent settings, from schoolyards to kitchens, prisons to farmhouses, churches to hotel rooms. Places where the performers went about their lives. And, for a moment or two, they got recorded, often constituting their sole time before a microphone. These myriad places, persons, and styles tell us that art is wherever you find it.

Musical traditions, like the life experiences of these singers and instrumentalists, are not monolithic. I found they all had different lessons to teach, just as the performers themselves amplified tradition’s gifts, each according to their talents. Varying circumstances had nurtured them, just as they absorbed influences and inheritances they made their own. In turn, these performances found new trajectories, inspiring still other interpreters.

Musical traditions, like the life experiences of these singers and instrumentalists, are not monolithic. I found they all had different lessons to teach, just as the performers themselves amplified tradition’s gifts, each according to their talents. Varying circumstances had nurtured them, just as they absorbed influences and inheritances they made their own. In turn, these performances found new trajectories, inspiring still other interpreters.

Yet when you ask about a common thread underlying their stories, I find myself thinking of something the book’s oldest performer once said. His name was Belo Cozad, and he was a Kiowa Indian. Born in 1864 (d. 1950), a flute maker and player, Belo recorded in 1941, not far from his home at an Indian school in Anadarko, Oklahoma. As he introduces his piece, he describes the folk process from a non-European perspective, establishing a kinship that he extends to his audience. On the recording (this particular track closes the book’s antecedent project, my 1997 Rounder CD 1500, A Treasury of Library of Congress Field Recordings) Belo describes an ancestor who went up on a mountain and, after four days, received this music from a spirit. Subsequently, Belo himself received that music as a gift. The piece he plays on his handmade cedar flute is rooted in that particular experience. His willingness to share a precious musical heritage with society in general, “and keep it, keep it as long as you live,” bears a heartwarming message. Time and again we see that the transfer of music in the human community proceeds by gift. On a fundamental level it’s this kind of openness, this capacious-hearted movement of cultural knowledge and creative expression from one person to another that his performance—and all these performances—have taken.

It’s also by this means this book came to be written. The openness of the people I visited, from the surviving performers and their families and communities, let alone the scholars who unsealed their files, and the musicians from whom in years past I learned to play, all of them have acted like Belo Cozad—sharing their knowledge with a stranger. Giving gifts, as he said, to keep as long as you live.

Chapter 16: You discuss the prevalent attitude at the time these field recordings were made—that the songs were more important than the story of the performers, so little or no biographical information was gathered for some recordings. Any ideas about what has changed about our culture to bring about more interest in individual performers?

Wade: One answer to your question might lie in our era’s ardor and interest in genealogy and its broadening view of personal identity. In years past, for example, generations that might not have embraced the presence of Native Americans among their ancestors, markedly differ today. We cleave to these lineages as new sources of pride and markers of depth. Similarly, this shifting from item to performer is something that speaks to changing priorities in scholarship. Some years back, writing about attitudes that surrounded the “Coal Creek March” (chapter eight in my book), Professor Neil Rosenberg addressed this matter so well. He wrote that, “The emphasis on biography is but the new orthodoxy and surely the next generation is shaping a response to it which will lead to new perspectives gathered to illustrate a different aesthetic.” And so it goes.

This widening of interest that stresses biography couples with evolving technological mediums that permit longer personal research encounters than before. Finite time limitations governed these disc machine recordings. Archival files bulge with weary field workers writing home to their superiors about the difficulties they faced in shipping and storing both blank and used discs—their weight and fragility—let alone the relatively few days they might have had to make these journeys. Compare that capacity to harvest information, a few minutes then, contrasted with the potential a tiny cellular device affords us today.

Chapter 16: For research of this type there always seems to be one more stone that can be uncovered. Have you encountered any new information or revelations since the publication of the book two years ago?

Chapter 16: For research of this type there always seems to be one more stone that can be uncovered. Have you encountered any new information or revelations since the publication of the book two years ago?

Wade: This book went into print in September 2012, and since then, I’ve had so many experiences that have surfaced new material, largely in the form of personal memories about the performers. Due to the generosity of several individuals—one patron in particular—I’ve been “bringing the book back home.” This support has allowed me to return to the communities where I did my research, driving from D.C. to Western Kentucky to Central Texas to the Mississippi Delta. This ongoing work, with more stops still ahead, has led to family gatherings at these public events. This has been so fulfilling. It’s this same impulse, in fact, that prompts my coming to Fisk. This book finds its spiritual home in the Fisk Memorial Chapel.

Chapter 16: The book’s title is derived from a remark John W. Work III made at Fisk University in 1941. Do you have any particular thoughts about your upcoming presentation at Fisk and the resonance of closing that circle?

Wade: I am overwhelmingly moved by this opportunity and grateful to John Work’s family, his friends, and the Fisk community for making this homecoming possible. Back in 1941, John Work spoke of, “a beautiful music all around you,” to describe the riches that Nashville offered its citizenry, a creativity he found brimming from its sidewalks to its churches. Years before that, in that same sanctuary, Work’s mentor, Charles S. Johnson, recounted “the surrounding beauties of our lives.” That richness these two wonderful scholars found encompassing their neighborhoods in Nashville extends to corners all across America and points beyond.