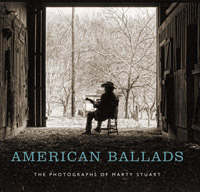

Balladeer in Black and White

American Ballads, Marty Stuart’s book of backstage photographs, captures a musical age

In a professional career that has spanned over forty years, musician, singer, songwriter, and collector Marty Stuart has participated in musical history. An accomplished photographer, he has also captured the images of that history as well as tableaux from his own life on the road. Edited by Kathryn Delmez, American Ballads: The Photographs of Marty Stuart is a new collection of Stuart’s photography; it accompanies the exhibit currently showing at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville. Divided into three sections—“The Masters,” “Blue Line Hotshots,” and “Badlands”—Stuart’s black-and-white photographs function like lines from classic ballads, conveying a concentrated slice from the larger stories of individuals, settings, and times that have nearly vanished from our homogenized, click-bait age of Internet memes and trending stories.

In her opening essay, Susan H. Edwards describes Stuart’s introduction to photography at the hands of his mother, Hilda Stuart, who worked in her uncle’s studio while she was in college and continued to pursue photography as a hobby while raising her family. She passed her love for visual imagery on to her son, even as he was becoming a musical prodigy.

In her opening essay, Susan H. Edwards describes Stuart’s introduction to photography at the hands of his mother, Hilda Stuart, who worked in her uncle’s studio while she was in college and continued to pursue photography as a hobby while raising her family. She passed her love for visual imagery on to her son, even as he was becoming a musical prodigy.

Marty Stuart’s own involvement with photography began in earnest after he joined the band of legendary bluegrass musician Lester Flatt. Stuart, who was only thirteen years old, accompanied Flatt to New York City in 1972. There, in a bookstore in Greenwich Village, Stuart saw the black-and-white photos of jazz musician and photographer Milt Hinton. Hinton’s behind-the-scenes images of jazz legends inspired Stuart to undertake a similar documentation of the many country and bluegrass legends he was encountering.

These photographs comprise “The Masters” section of American Ballads. A mix of casual shots and posed portraits, Stuart’s photographs are peeks behind the mask of fame as legendary figures like Johnny Cash and Ray Charles share a moment of laughter in the studio or Willie Nelson is captured on stage before an empty auditorium, strumming his famous gut-stringed acoustic guitar for an audience of one. But the most powerful images in the “The Masters” section speak to the lost world of the country-music legends. We live in age where artistic expression and the desire for celebrity are the driving forces behind most musical careers. For the generation immediately preceding Stuart’s, however, musical success provided a very real path out of a life of crushing poverty and hard labor.

That era is reflected in many of Stuart’s images: the dilapidated cabin where country-music patriarch A.P. Carter first plotted his musical escape from the hills of Virginia; Bill Monroe playing his mandolin for a flock of barnyard fowl; Kitty Wells, the “Queen of Country Music,” both regal and demure as her makeup is applied backstage. All of these photographs spotlight individuals from simple backgrounds who dared to grasp for hillbilly dreams of glory.

That era is reflected in many of Stuart’s images: the dilapidated cabin where country-music patriarch A.P. Carter first plotted his musical escape from the hills of Virginia; Bill Monroe playing his mandolin for a flock of barnyard fowl; Kitty Wells, the “Queen of Country Music,” both regal and demure as her makeup is applied backstage. All of these photographs spotlight individuals from simple backgrounds who dared to grasp for hillbilly dreams of glory.

In the second section of the book, “Blue Line Hotshots,” Stuart turns his camera toward the ordinary eccentrics and personalities that fill the American landscape—people who are the reigning stars of their own life stories that stretch both backward and forward from the moment captured by Stuart’s camera. Whether an anonymous fan at a concert, a stern-faced evangelist posing for a portrait, or an Elvis impersonator singing karaoke at a county fair, they all inspire curiosity about the next verse of their personal ballads.

The final section of American Ballads “Badlands,” is a collection of images Stuart gathered on his many visits to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in Shannon County, South Dakota, site of the infamous Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 and one of the poorest counties in the United States. While it would be simple to find images of destitution and hopelessness in such a location, Stuart instead turns his camera to capturing the nobility, pride, and hope of people living under the burden of decades of broken treaties, broken promises, and broken hearts.

As Stuart spells out in his introductory text, the common thread that runs through American Ballads is the fierce spirit of individualism in his subjects. That same spirit informs the talent behind the camera and makes Stuart’s photographic journeys sweet melodies to behold.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.