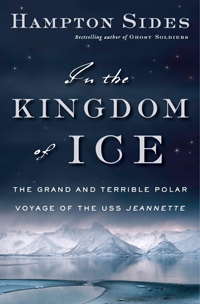

Polar Odyssey

With In the Kingdom of Ice Hampton Sides captures the horror and heroism of nineteenth-century exploration

“History” and “suspense” might seem to be opposite terms. How can a part of the historical record—a story involving verifiable events, lived by well-documented people—ever be suspenseful, keeping readers up far into the night, waiting to see who lives and who dies? Successful suspense writers invent believable heroes, villains, and action, but the scrupulous historian is allowed no invention beyond good sentences, even when source material is in short supply.

If historical events have occurred recently, an author can overcome a paucity of documentation by interviewing survivors and eyewitnesses, using their accounts to build engrossing scenes of action and conflict. Jon Krakauer used this technique masterfully in Into Thin Air, the story of a disastrous 1996 expedition to Mt. Everest, as did Sebastian Junger in The Perfect Storm, which focused on an ill-fated fishing trip in 1991. But how can an author achieve similar suspense when all survivors and witnesses are long dead?

Memphis native Hampton Sides hits the mark squarely with In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette, a gripping account of a star-crossed expedition that began in 1879 and lasted three years. Like Krakauer and Junger, Sides (whose previous historical bestsellers include Ghost Soldiers and Hellhound on His Trail) tells a story that pits a small band of memorable characters against intractable nature at its most furious.

Part of Sides’s genius in this book is that the adventure he’s chosen to write about was well-chronicled by several participants—in some cases participants whose records survived even if they themselves did not. The crew’s fate became common knowledge in the 1880s, yet most modern readers are familiar only with more recent polar explorers like Robert Peary and Frederick Cook. All readers of In the Kingdom of Ice will know with certainty as the voyage progresses is that at least some of the crew survive.

Part of Sides’s genius in this book is that the adventure he’s chosen to write about was well-chronicled by several participants—in some cases participants whose records survived even if they themselves did not. The crew’s fate became common knowledge in the 1880s, yet most modern readers are familiar only with more recent polar explorers like Robert Peary and Frederick Cook. All readers of In the Kingdom of Ice will know with certainty as the voyage progresses is that at least some of the crew survive.

Led by Captain George De Long, a methodical and driven naval officer, the Jeannette sailed at the height of a scientific and nationalistic fervor to reach the globe’s last true terra incognita, the North Pole. For nineteenth-century Americans, living in a time before aircraft or metal ships, the pole remained as remote as the moon. Less was known about it scientifically because the moon, at least, could be seen. At the time of its sailing, the Jeannette was the first official U.S. expedition to attempt the pole.

Designed to withstand the stress of drifting within pack ice—which the ship successfully accomplished for over two years and 600 nautical miles—the Jeannette seems more spacecraft than steamer, its crew carrying civilization into an alien world for years. With no possibility of outside communication, keeping accurate logs and journals was paramount. Here is Sides describing a particular morning during the first year within the ice:

About the time the sun vanished, the ice began to move again. The noise was terrible—first the sounds of the ice warring with itself, then the more dreadful sounds of the ice warring with the ship. The turbulence started early on a cold November morning. De Long was awakened by a “grinding and crushing—I know of no sound on shore that can be compared with it,” he said. “A rumble, a shriek, a groan, and a crash of a falling house all combined might convey an idea.”

He went outside to study the pack, which he likened to “a marble yard, adrift.” Soon others joined him on deck. To Melville, it sounded at first like “distant artillery” but then it grew louder. “Giant blocks pitched and rolled as though controlled by invisible hands, and the vast compressing bodies shrieked a shrill and horrible song.”

This level of direct, personal-point-of-view reporting continues throughout the book, even as the men are forced to abandon ship and begin a thousand-mile journey, at first on foot across the ice, then on tiny boats across the treacherous Arctic ocean, and finally over nearly impassable Siberian tundra. How many make it, and how they do so against increasingly difficult odds, remains a mystery until the final chapter (so long as the reader can resist the ever-present urge to Google the expedition).

Scene by scene, the prose reads like that of Krakauer and Junger, even though the events described took place more than 130 years ago. This may be no accident: like those authors, Sides was forged by a great American factory of adventure writers: Outside magazine. Both Into Thin Air and The Perfect Storm began as feature articles for the magazine; as an Outside editor-at-large, Sides has written adventure features for over a decade and persuaded the magazine to send him to northern Siberia to walk the frozen path of Jeannette survivors. (He also visited Wrangel Island, another key locale in the book, to write an article for National Geographic magazine.)

Scene by scene, the prose reads like that of Krakauer and Junger, even though the events described took place more than 130 years ago. This may be no accident: like those authors, Sides was forged by a great American factory of adventure writers: Outside magazine. Both Into Thin Air and The Perfect Storm began as feature articles for the magazine; as an Outside editor-at-large, Sides has written adventure features for over a decade and persuaded the magazine to send him to northern Siberia to walk the frozen path of Jeannette survivors. (He also visited Wrangel Island, another key locale in the book, to write an article for National Geographic magazine.)

One of the great casualties of the ever-shrinking magazine industry may be the kinds of books that gestate from good features. Many of the best recent nonfiction books began with a magazine writer sent deep into the field, but the next Hampton Sides or Jon Krakauer will have a much harder time reaching Siberia or Everest for the first-hand reporting that can make scenes come alive. But perhaps the answer to funding the great adventure writing of the future lies within In the Kingdom of Ice itself. One of the book’s most memorable characters is James Gordon Bennett, patron of the expedition and playboy publisher of The New York Herald. Bennett spent a small fortune on Arctic research, and an even larger one to build and equip the Jeannette. He had earlier gained wide attention (and sold a great many newspapers) by sending Stanley to Africa to search for Livingstone. In doing what the U.S. Navy could not afford to do—i.e., outfitting an expedition with a shot at the pole—he ultimately achieved the same notoriety with De Long’s adventure.

As a publisher, of course Bennett was after good stories—he sent a pun-loving reporter named Collins along as a crew member on the Jeannette—but he far outspent the needs of any story as a patron of exploration for its own sake. (He also spent vastly on other interests, founding a tennis club to host what we now call the U.S. Open and building great casinos in America and Europe). Underwriting exploration became almost a public penance for his many personal failures, including ruining a swank Christmastime engagement party (not to mention his own planned marriage) with his drunken behavior at the mansion of his would-be in-laws. Sides caps the scene succinctly: “Standing beside the grand piano, he unbuttoned his trousers and, in plain view of the guests, began to relieve himself, arcing a stream into the innards of the instrument.”

For all their human weaknesses, the book’s larger-than-life characters like Bennett and De Long pull the reader into the story, and the grandeur of the polar landscape—as well as the terrible struggle for survival—keeps them there. “It was a severe country, a land that seemed better suited for mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, and wooly rhinos,” Sides writes of northern Siberia, “a Pleistocene tundra on a fantastic scale.” In the Kingdom of Ice is a book to make readers nostalgic for the late-nineteenth century’s golden age of arctic exploration, even as it makes reviewers nostalgic for the late-twentieth century’s great magazine adventure writing. Hampton Sides has captured the best of both, turning history into nail-biting suspense.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of three traditional books of nonfiction—Cave Passages, Dark Life, and Caves—as well as The Cat Manual, an ebook.