Under Fire

For memoirist Frances Mayes, childhood was a powder keg

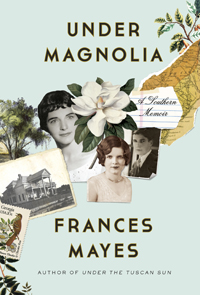

“I want to move back to the South,” Frances Mayes told her husband in Tuscany, the setting for Mayes’s megabestelling memoir, Under the Tuscan Sun (along with several sequels), and two years later the couple set up housekeeping in Hillsborough, North Carolina. During the move, Mayes found a box of childhood memorabilia filled with photographs, diaries, and scrapbooks from her childhood in Fitzgerald, Georgia, where her family was wealthy but troubled. The resulting memoir is Mayes’s moving account of coming of age as a young woman destined to be a poet, teacher, and autobiographer. “We were not normal,” Mayes writes in Under Magnolia. “We lived next door to normal people, so I knew what normal was.”

Mayes describes a precarious life, weaving her way around the sometimes unrestrained violence of her gin-soaked parents. She spent long hours hiding—in the depths of a rag bag or inside her bedside table—to avoid her father, who in his rages might upend the card table or rip down the chintz curtains. “Every night was chaos,” she writes. “They shouted and slammed doors, roaring off in the car in the middle of the night. They acted out every bad play they invented. Dingbat fights began with the whereabouts of keys and bills. At bedrock, I sensed that my parents loved each other. I still feel that was true, still never have broken their code of relentless ornery behavior, the determination to stay in motion, spiders, continuing to spin out the same tensile thread.”

Mayes describes a precarious life, weaving her way around the sometimes unrestrained violence of her gin-soaked parents. She spent long hours hiding—in the depths of a rag bag or inside her bedside table—to avoid her father, who in his rages might upend the card table or rip down the chintz curtains. “Every night was chaos,” she writes. “They shouted and slammed doors, roaring off in the car in the middle of the night. They acted out every bad play they invented. Dingbat fights began with the whereabouts of keys and bills. At bedrock, I sensed that my parents loved each other. I still feel that was true, still never have broken their code of relentless ornery behavior, the determination to stay in motion, spiders, continuing to spin out the same tensile thread.”

In this uncertain world, the most steadfast figure is Willie Bell, the family cook. Mayes and Willie “were in it together,” but the cook’s comfort was sparse: “Just run out and play,” she would say; “try not to pay them any mind, they all crazy.”

Prior to her appearance at the Southern Festival of Books, Mayes answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: How did returning to the South inspire Under Magnolia? Was there a Proustian moment when all the childhood pain came tumbling back to you?

Frances Mayes: Under Magnolia was written in pieces, some going back twenty years, so returning to the South didn’t catapult the process. Unpacking after moving, I came across the long-lost chapters, which I’d hidden away because of family objections. Much time had passed so I thought again of bringing my memoir to the light. I wrote new chapters, revised the existing ones, and thoroughly enjoyed the writing. There were many Proustian moments, many of joy at reconnecting with the deep metabolic sense of home that came back to me as I learned to live in the South I’d long ago fled.

Chapter 16: Under Magnolia is more personal, more raw, than Under the Tuscan Sun. How would you compare the experience of writing the two books?

Chapter 16: Under Magnolia is more personal, more raw, than Under the Tuscan Sun. How would you compare the experience of writing the two books?

Mayes: You’re right. Under the Tuscan Sun, while personal, is not intimate. Under Magnolia is. My five Italian books are present tense, immediate, written out of the pleasures of living in a foreign culture, making Italian friends, learning the language, writing, gardening, traveling and cooking. They’re a kind of Very Rich Hours, all of them. They were written with spontaneous energy.

My Southern memoir goes back to beginnings and tries to figure out who we were way down South so long ago. The material felt primordial to me. Dangerous. And at the same time exhilarating. In a chaotic family, I learned early to appreciate irony and therefore humor. Crazy as they are, my memories are laced with both. I’m fascinated always by the workings of memory and, writing Under Magnolia, I had the chance to question what is remembered and why, how to guide a narrative through a maze, and how to let the memory speak for itself without over-reaching interpretation or intervention. Writing a memoir gives you the gift of putting memory into a context, which magically tames it. Though my Italian books and this memoir are all memoir, they feel like different genres to me.

Chapter 16: Your portrayal of your parents is both clear-eyed and, despite their flaws, loving—or at least forgiving. Did it take time, even as you were writing, to come to terms with both the damage and the gifts they gave you?

Mayes: I think children know everything. I did. I was clear-eyed even at nine that my parents were unpredictable, out of control, loving, thwarted, generous, mean, fun, beautiful, thoughtless, sentimental, violent. So, the damage and the gifts—they were always apparent. What the writing gave me as a gift was the idea to try to see them both as they were before I was born, their youths, before they became their adult selves. I then saw them more openly—from their perspective rather than my own.

Chapter 16: No matter how bad parents are, most children survive, and no matter how well-meaning we are, most of us still manage to damage our children in some way. Did writing this memoir in any way change your feelings as a mother?

Mayes: Ha! Maybe just hoping that my daughter never writes a memoir! Because of my upbringing, I set out to give my daughter the perfect childhood. Never would I allow her to have to put up with an unstable family. I succeeded for more than a decade; then I had to divorce her father, and, of course, the walls came tumbling down. Writing the memoir reinforced to me just how sacred is the office of being a parent and how easily the privilege can be abused.

Chapter 16: You talk about some of the cultural similarities between Italy and the South: the generational stability, for example, and the manners that emphasize friendliness. In your experience, what are the most salient differences between them?

Mayes: Well, Italy had the Renaissance! Art is a natural occurrence, and the Italians are at home with art. You don’t feel like a freak if you say you’re a poet. The patrimony of art is so extensive that you simply breathe art. I love that. Art is not separate and off to the side. Also, there’s a sense of long-time that lives in every Tuscan, and this gives them a relaxation around how a simple day proceeds. What I love most is the life of the piazza. You go every day, you meet your friends, your business with the electrician is settled, you shop here and there for cheeses and wines and fruits, you exchange recipes in the butcher’s, and you have time for coffee with someone you bump into. A sense of intense community, which existed in the town where I grew up but is now, in America, not that easy to find. The closest I’ve come is the town of Hillsborough, where we live in North Carolina.

Chapter 16: You are both a poet and a memoirist. Does one genre have a stronger hold on your heart?

Mayes: On a long drive, I recently listened to the poems of [Gerard Manley] Hopkins. I loved him as a college student and was surprised to find that I still remembered word-for-word many, many of his poems. There’s something in good poetry that charges the brain synapses more than any other kind of writing. Poetry is my first love. My husband, Ed, is a poet, so we live poetry around our house. It surprised me when my writing suddenly one summer slipped into prose. Why? The experiences I was having in Italy just kept provoking longer lines, and finally I realized that I was writing prose. Mysterious for me, but I never went back to writing poetry. I loved the expansive and free feeling prose gave me, and, somehow, I felt that I moved away from my dark side. Oddly, what I read most is fiction—two or three novels a week. In a way, writing is writing for me. The form finds itself from the material.

Lyda Phillips is a veteran journalist who grew up in Memphis and has earned degrees from Northwestern, Columbia, and Vanderbilt universities. The author of two young-adult novels, she worked for United Press International before returning to Nashville.