Tossing a Firecracker into Journalism

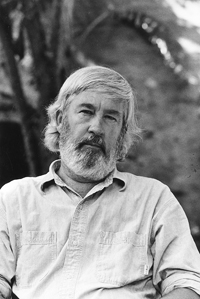

Curtis Wilkie is much more than a political reporter or a Southern colorist

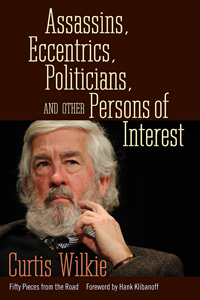

More than forty years later, journalist Curtis Wilkie is still best known as a cast member from The Boys on the Bus, Timothy Crouse’s acerbic account of the reporters who covered the 1972 presidential campaign. The back cover of Assassins, Eccentrics, Politicians, and Other Persons of Interest, a new collection of Wilkie’s writing, acknowledges as much, calling the book “a compilation from the incomparable career of one of the original Boys on the Bus.”

This is both very true and very unfair. It is true in that Wilkie is incomparable, and that he was one of Crouse’s “boys”—one of the few who escaped the worst of the Rolling Stone writer’s barbs—and that he represented, way back when, a new generation of hard-nosed, globetrotting reporters.

This is both very true and very unfair. It is true in that Wilkie is incomparable, and that he was one of Crouse’s “boys”—one of the few who escaped the worst of the Rolling Stone writer’s barbs—and that he represented, way back when, a new generation of hard-nosed, globetrotting reporters.

But it’s unfair because, as this volume makes clear, Wilkie was, and remains, much more than just a boy on the bus. Tellingly, none of Wilkie’s reporting from his time on the bus appears in Assassins. In 1972 he was still learning his trade, working hard enough to impress Crouse by filing two stories a day for his employer, The News Journal of Wilmington, Delaware.

Despite an earlier, award-winning career at The Clarksdale Press Register in Mississippi, which he joined fresh out of Ole Miss, Wilkie didn’t really hit his stride until he moved to The Boston Globe in 1975. There he became, whether he liked it or not—and it’s not clear which—the house Southerner, whose deep Delta drawl alternately amused and confounded his editors.

In his forward, reporter Hank Klibanoff recounts a story in which Wilkie called in a report from a debate in Iowa during the 1980 presidential campaign. The next day, while the rest of the papers reported on the candidates’ farm-policy debate, Wilkie’s piece in the Globe recounted their debate on foreign policy—a mix up due, apparently, to the transcriber’s inability to distinguish Wilkie’s enunciation of “fawn policy” from his rendering of “fawm policy.”

No matter. Whatever cross-cultural confusions Wilkie’s heritage visited upon the good folks in the The Boston Globe newsroom were more than made up for by his dogged reporting skills, his keen eye for detail, and, above all, his unmatched understanding of the South at the exact moment when Southern politics were becoming national politics.

Wilkie’s first major assignment at the Globe was to cover the upstart former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, and his successful run for the presidency in 1976 (as well as his failed run four years later). Wilkie eventually took up residence in Plains, Georgia, Carter’s home base, and his reports from the peanut field are worth reading in full—especially a heartbreaking account of the eviction of a neighboring family of black tenant workers, the victims of a sort of rural gentrification during Carter fever in Georgia. Just as touching, if a good bit funnier, are his stories about hanging out with Carter’s ne’er-do-well brother, Billy, who once ran for mayor of Plains from the front stoop of his service station, down the road from Jimmy’s spread.

But Wilkie is much more than a political reporter or a Southern colorist. From the early 1980s to the early ’90s, he reported on the Middle East, first as a correspondent in Jerusalem and later covering the first Gulf War. Assassins makes clear his affinity for the Palestinian cause—Wilkie calls A.B. Yehoshua “Israel’s Faulkner,” which, given where Faulkner came from, is an astoundingly harsh, if indirect, indictment of Israeli society—but they are also filled with a searching sympathy for all sides, an attempt to understand how such brutal enemies came to be locked in unending, close-quarters combat. I’m not sure if it’s depressing or comforting that, thirty years later, Wilkie’s descriptions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict still feel fresh.

But Wilkie is much more than a political reporter or a Southern colorist. From the early 1980s to the early ’90s, he reported on the Middle East, first as a correspondent in Jerusalem and later covering the first Gulf War. Assassins makes clear his affinity for the Palestinian cause—Wilkie calls A.B. Yehoshua “Israel’s Faulkner,” which, given where Faulkner came from, is an astoundingly harsh, if indirect, indictment of Israeli society—but they are also filled with a searching sympathy for all sides, an attempt to understand how such brutal enemies came to be locked in unending, close-quarters combat. I’m not sure if it’s depressing or comforting that, thirty years later, Wilkie’s descriptions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict still feel fresh.

On returning home, Wilkie persuaded his editors to let him write from New Orleans as a national correspondent. Unfortunately, Assassins contains just one piece about the city itself, an article he wrote for The Nation after Hurricane Katrina; it would be nice to know what the author of a book called Assassins, Eccentrics, Politicians, and Other Persons of Interest thinks of a town that could well claim to have invented each of those categories. In any case, Wilkie’s base in New Orleans was just that—a base—because soon he was covering Bill Clinton, first as candidate and then as president.

As with Carter, Wilkie was impressed by Clinton but not sold on him; like any good reporter, he is both attracted to political power and slightly repulsed by the people who wield it. One of the single best pieces in the collection—and one of the best pieces of political reporting you’ll find anywhere—is an insider account of Clinton’s rise and fall and rise again during the days before the 1992 New Hampshire primary, when tabloid reports of the Arkansas governor’s trysts began to percolate into the mainstream media, and Clinton had to dig deep within himself to right his campaign’s suddenly sinking ship.

While that may be the best piece in Assassins, surely the most enjoyable is a long profile Wilkie wrote for The Boston Globe Magazine about another one of the boys on the bus, Hunter S. Thompson. In a brief introduction to the piece, Wilkie calls it a parody, and he does borrow some of the syntax and style of Thompson’s dispatches. But he does so with a professional restraint that shows how a little bit of gonzo shtick will indeed go a long way. In a manner than has been mostly wrung out of today’s digitally enhanced journalism, Wilkie has a knack for tossing the occasional firecracker of a line into an otherwise straight story. To wit: “An avowed speed freak, he can go several days without rest. The night does not belong to Michelob; it belongs to Hunter Stockton Thompson.”

It is tempting to close Assassins, reach for a bottle of bourbon, and sigh about how they don’t make them like they used to. But Wilkie’s work should inspire, not depress. There is no magic here, just good journalism—and as Wilkie’s career demonstrates, you don’t have to ride around on a bus to practice it.

Nashville native Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination and American Whiskey, Bourbon and Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. His new book, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, appeared in spring 2014. He lives in New York, where he is an editor at The New York Times.