Sun of the South

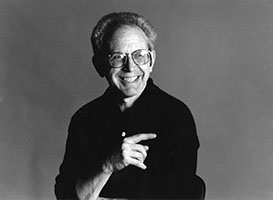

Peter Guralnick delivers a thorough, affectionate biography of Sam Phillips, “the man who invented rock ‘n’ roll”

If you know a little something about Sam Phillips, you probably know his famous remark: “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars!” You also probably know that the white man he discovered was Elvis Presley and that Phillips’s label, Sun Records, popularized a new rock ‘n’ roll sound that transformed American music. And so you might assume that Phillips was calculating racial attitudes, appropriating black music, and gauging the market for a big score.

But whenever Phillips made this statement, Peter Guralnick contends, he would laugh, “as if to underscore that money was never the point—it was the vision, it was what would come afterward.” Informed by a long relationship with Phillips and a longer career as a great American music writer, Guralnick has produced a sprawling, engaging biography stuffed with stories and tidbits. He argues that Sam Phillips was an idealist devoted to principles of individualism, authenticity, freedom, and racial enlightenment. Guralnick is clearly fond of his subject, as indicated by his new book’s complete title: Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll: How One Man Discovered Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley, and How His Tiny Label, Sun Records of Memphis, Revolutionized the World!

But whenever Phillips made this statement, Peter Guralnick contends, he would laugh, “as if to underscore that money was never the point—it was the vision, it was what would come afterward.” Informed by a long relationship with Phillips and a longer career as a great American music writer, Guralnick has produced a sprawling, engaging biography stuffed with stories and tidbits. He argues that Sam Phillips was an idealist devoted to principles of individualism, authenticity, freedom, and racial enlightenment. Guralnick is clearly fond of his subject, as indicated by his new book’s complete title: Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll: How One Man Discovered Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley, and How His Tiny Label, Sun Records of Memphis, Revolutionized the World!

Since his childhood in Florence, Alabama, Phillips believed that black music could transform the soul. He heard the resilient beauty of sharecroppers’ spirituals, and as a teenager, on his first trip through Memphis, he encountered Beale Street, where he saw a man fashioning a drum set out of a broomstick and a can of lard. Phillips felt he belonged there.

A decade later, as World War II was ending, he was working in radio and moved to Memphis: “It started tugging at him more and more: the original dream, however inchoate, that had brought him to Memphis, the sense that there were all these people of little education and even less social standing, both black and white, who had so much to say but were prohibited from saying it.” Phillips believed in his own destiny, too, “to bring it out of them, to coax out of them the inarticulate speech of the human heart.” He opened a small studio at the corner of Union and Marshall.

There he recorded black artists, urging a loose, energetic, rhythmic aesthetic. Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston made “Rocket 88,” which has been called the first rock ‘n’ roll song. Rufus Thomas sang “Bear Cat,” a fun response to Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog.” Phillips’s greatest hopes lay with Howlin’ Wolf, a Mississippi bluesman with a potent voice, compelling energy, and particular pureness of the spirit—exactly what Phillips was seeking. It was all great music, a new sound that appealed to teenagers, both black and white. But the distributors and jukebox operators resisted the race-mixing implications. Phillips was at a crossroads.

There he recorded black artists, urging a loose, energetic, rhythmic aesthetic. Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston made “Rocket 88,” which has been called the first rock ‘n’ roll song. Rufus Thomas sang “Bear Cat,” a fun response to Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog.” Phillips’s greatest hopes lay with Howlin’ Wolf, a Mississippi bluesman with a potent voice, compelling energy, and particular pureness of the spirit—exactly what Phillips was seeking. It was all great music, a new sound that appealed to teenagers, both black and white. But the distributors and jukebox operators resisted the race-mixing implications. Phillips was at a crossroads.

Then came Elvis. It may now be a familiar story—thanks especially to Guralnick himself, the author of the definitive two-volume biography on Presley—but it is recounted here with spark and insight. In Elvis, Phillips saw a kindred soul, someone who was just different, with real passion and a perfect set of contradictions: earnest with a hint of danger, spiritual but wafting sexiness, polite yet somehow impudent, white with an undercurrent of blackness. Out of one long recording session, guided by a searching Sam Phillips, they hit upon “That’s All Right, Mama,” and the Elvis phenomenon was born. For Phillips, it was more than creating a star, more than saving Sun Records—“it was the limitless prospects that Elvis Presley’s music unleashed.”

Phillips agonized that championing Elvis meant abandoning blacks, but he rationalized that he was forging a new musical space that blurred race lines. Though this argument offered little comfort to musicians like Rufus Thomas, who thought Phillips was just ditching his black talent, Phillips found prosperity with people just like him: poor white country boys who had migrated to Memphis. Carl Perkins, like Elvis, spread the new rockabilly sound that melted the old musical categories of country, pop, and r&b. Johnny Cash originally thought himself a gospel singer, but Phillips lured out an up-tempo, hard-driving style that fit Cash’s natural panache.

And there was Jerry Lee Lewis. According to Guralnick, Phillips believed Lewis was the greatest natural talent ever to pass through Sun Records: “Not the most charismatic (that would be Elvis), not the most commanding (that probably would be Cash), not the most profound (that would unquestionably be the Wolf), but the most versatile, the most innately musical, the one who took the most pure pleasure and delight in his music.” Driven by Lewis’s astonishing skill and Phillips’s astute production, “Great Balls of Fire” introduced the brash young star to the world.

Guralnick vividly captures the rise of rock ‘n’ roll through the careers of the Sun artists: recording sessions, concerts, business deals won and lost, triumphs of fame, and tragedies of scandal. But the central thread in Sam Phillips is Phillips himself. Stirred by nervous energy, he sometimes suffered as his mind roiled with anxiety—twice, in his early adulthood, he volunteered for electroshock treatment. He had a close but troubled relationship with his charismatic, unreliable brother Jud, who both helped and hurt Sun Records. He craved love and attention. He inspired romantic devotion from a succession of women, while unapologetically switching his own loyalties as suited his individual needs.

Phillips sold Sun Records in 1964, by which time his great artists had fled for more profitable pastures. The biography ends with two huge, rambling chapters devoted to the years after Phillips quit shaping great American music. In a loose, conversational tone that often includes his own first-person accounts, Guralnick explores how Phillips sought to mold the public memory of his life and career. He was sometimes bitter and often inscrutable, but he aroused a warm devotion from family and friends, including Guralnick, who gave a eulogy at Phillips’s 2003 funeral. To the end, Phillips painted the history of Sun Records as one of artistic and racial freedom. Guralnick chronicles that story with grace and affection.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.