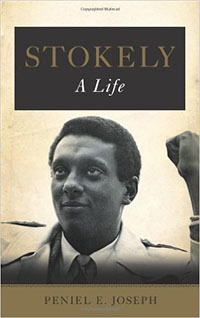

Black Power’s Prophet

Peniel Joseph chronicles the life of Stokely Carmichael, a global icon of revolution

Howard Zinn once wrote that Stokely Carmichael “would stride cool and smiling through Hell, philosophizing all the way.” Carmichael was a dynamic, confident organizer during the civil-rights movement, always on the radical vanguard, and he grew into a figure of great international significance. It was Carmichael who popularized the slogan “Black Power,” which defined an emerging movement of both inspiration and controversy. In his award-winning biography, Stokely: A Life, Peniel Joseph deftly narrates the political journey of a global icon.

Joseph holds a joint appointment at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a professor in the department of history and founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. In recognition of his National Book Award from the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change, he recently answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Joseph holds a joint appointment at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a professor in the department of history and founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. In recognition of his National Book Award from the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change, he recently answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: In the late 1960s, Stokely Carmichael was one of the most polarizing figures in American culture, yet he seems somewhat forgotten by many people today. What accounts for this lapse in our historical memory?

Peniel Joseph: Stokely Carmichael’s revolutionary praxis made him an icon that people wanted to forget. He remained an unrelenting critic of liberal democratic capitalism, and he defined America as a global empire that pretended to be a democracy. His critique of white supremacy, institutional racism, and imperialism made him a figure that the nation has steadfastly refused to acknowledge, even though such recognition is vital to the radical political transformation needed to finally achieve racial equality and economic justice.

Chapter 16: Should we think of the young Carmichael as an outsider? He was an immigrant from Trinidad, and he was a black student at the predominantly white Bronx High School of Science. How might these experiences have shaped his participation in the civil-rights movement?

Joseph: He was both an insider and an outsider—really, a participant observer. These experiences certainly shaped him as a young man. He refused to let America’s version of anti-black racism put intellectual or experiential limits on his own imagination. He grew up confident, a voracious reader, and one who was not intimidated in any way by white Americans.

Chapter 16: Carmichael participated in some of the signature events of the civil-rights movement, from the Freedom Rides to Freedom Summer. What was his larger role in the movement? Did his ideology change during the 1960s?

Joseph: Stokely served as one of the key student organizers and leaders at Howard University’s SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] affiliate, NAG (Nonviolent Action Group). He was a key leader, organizing Mississippi’s Second Congressional District during Freedom Summer and becoming one of the lead organizers in Lowndes County, Alabama, where local activists and SNCC organized an independent black party that was nicknamed the Black Panther Party. As SNCC chairman, Stokely became the youthful face and main political mobilizer of Black Power radicalism and anti-war activism. Political and historical circumstances transformed Carmichael, who initially believed that American democracy might be saved by the blood, sweat, and toil of black sharecroppers. He came to change these views by the late 1960s, advocating revolutionary Pan-Africanism under the leadership of African revolutionaries Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Sekou Toure of Guinea.

< b>Chapter 16: Carmichael vaulted into the public consciousness in June 1966, on the Meredith March Against Fear, when as the new chairman of SNCC he called for “Black Power.” What did Black Power mean to Stokely Carmichael?

b>Chapter 16: Carmichael vaulted into the public consciousness in June 1966, on the Meredith March Against Fear, when as the new chairman of SNCC he called for “Black Power.” What did Black Power mean to Stokely Carmichael?

Joseph: Carmichael initially identified Black Power as radical political, cultural, and economic self-determination—that is, black people redefining themselves for themselves and in contrast to Western civilization’s unapologetically racist views of blacks and Africa. Over time he defined Black Power as one expression of revolutionary Pan-Africanism, which he came to characterize as Black Power’s highest expression. He changed his name to Kwame Ture in honor of his political mentors and came to believe that only a United States of Africa, one guided by the principles of scientific socialism, could help liberate black America and the entire world.

Chapter 16: What made Carmichael such a compelling figure by the late 1960s? Why did so many hate him, and why did so many others revere him?

Joseph: He was intelligent, good-looking, charismatic, and courageous. Stokely, alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, was in love with black people. He especially loved poor black folks. As the author of the definitive history of the Meredith March, your important scholarship has revealed this in expert detail. Carmichael’s love for black people—and remember he lived with black sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta and the Alabama Black Belt for years—galvanized him and the entire community. His fearless devotion to justice helped make Black Power a generational clarion call. We would not be black and beautiful people in America and around the world without Stokely Carmichael. His efforts embolden and amplify the work of Malcolm X, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Angela Davis, the Black Panthers, the Black Arts Movement, local activists, and international movements for Black Power. He is an avatar of this period who stands alongside Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. in bestriding the global stage of postwar decolonization.

Chapter 16: Stokely Carmichael was a global icon. He toured London, Cuba, Vietnam, Algeria, Syria, and elsewhere, and the African nation of Guinea was his home base for the second half of his life. What impact did he have beyond American borders?

Peniel Joseph: His worldwide impact was indelible. He became the global face of revolutionary Pan-Africanism at a historical moment when African liberation was still unfolding in dramatic colonial and civil wars. He became a bridge and conduit to a diverse and eclectic network of international revolutionaries that traversed Africa, the Middle East, Europe, the Caribbean, and the United States.

Chapter 16: Some might argue that Carmichael’s later years were an extension of his activism in the 1960s, and others might argue that it was a retreat from the grassroots organizing of those years. How should we consider his political function in the years after he left the United States?

Peniel Joseph: Kwame Ture was a political mobilizer, revolutionary propagandist, public intellectual, and still a globally recognized organizer. His geopolitical focus shifted from local and national organizing in America to organizing on behalf of a global pan-African revolution. The thousands of speeches he gave during this period reflect a powerful legacy of tireless activism that helped inspire new generations to freedom’s cause and human-rights struggles taking shape around the world.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.