Reconsidering My Whole Position

Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize-winning poems finally allowed Kate Daniels to call herself a Southern writer

Even though I was born and raised entirely in the South—born, in fact, in a Richmond hospital named for Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart—the first time I recall consciously thinking of myself as a “Southern” writer was in the late 1970s. I was twenty-five, a graduate student at Columbia University. I had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English literature at the University of Virginia, and then booked it for Los Angeles, where I lived for a year and a half before moving to New York in the fall of 1978 to pursue an M.F.A. I often felt, with relief, as if I might no longer be a true Southerner. Somehow, I had avoided a close call with a bad destiny.

Although I couldn’t have articulated it then, I had always been a conflicted Southerner—a conflicted white Southerner. Almost from the beginning of consciousness, I had spent a good deal of my childhood wishing myself out of the region that spawned me. My first disavowal was based on language: I disliked the sound of my own Southern accent.

Although I couldn’t have articulated it then, I had always been a conflicted Southerner—a conflicted white Southerner. Almost from the beginning of consciousness, I had spent a good deal of my childhood wishing myself out of the region that spawned me. My first disavowal was based on language: I disliked the sound of my own Southern accent.

Part of this feeling must have come from having an English mother, a G.I. bride of World War II. I idealized my mother’s speaking voice, so different from mine: the accent that remained ineradicable over the years, her impeccable grammar, and her recitations of lengthy narrative poems she had memorized in grade school. Although she came from Lancashire folk of modest means, Mother had absorbed (and passed on to me) a surprisingly intellectual set of values that included the ordinary Englishman’s respect for spoken language and literature, a sense of the dignity of working people, and an astonishing lack of prejudice against people of color. (This last attribute would be worn out of her by sixty fractious years of impoverished life in the American South, but as a young woman she impressed upon me the beauty of human diversity.)

My father’s family could hardly have been more different. They were people whose kin had only recently moved up to Richmond from the small farms that had sustained them since the end of the eighteenth century. Although many of them fought in the Civil War, none had been slaveowners, a fact that almost certainly originated from economic imperatives, rather than from moral convictions. By 1920, many members of my father’s family, including my grandparents, had relocated to the city, where they worked as unskilled laborers in the tobacco companies. None of them had gone beyond junior high school. As far as I know, none of them ever exhibited a feel for art, respect for higher education, or a love of literature. They spoke ungrammatically, sprinkling their talk with ain’ts and not hardlys and might coulds—illiteracies that fit right in with their Southern accents, oozing with broad vowel sounds and consonants lopped off lazily at the ends of words. I loved them—mightily in most cases—but their language, especially compared to the literary qualities of my mother’s, shamed me.

When I got to graduate school, I thought I had escaped embarrassment of my origins when I found myself living away from the South among a group of new friends, all but one of them from New York City. I loved how rapid and percussive New York speech was, and how alive it felt in my mouth when I was mimicking what I heard on the street. In New York, the sound of ordinary people talking was something like a communal stir fry—sizzling, fast, and spicy. In the South, speech stalled in my mouth—a lukewarm, overly sweetened, mushy pudding I didn’t care for. Linguistically, I committed to changing my diet.

When I got to graduate school, I thought I had escaped embarrassment of my origins when I found myself living away from the South among a group of new friends, all but one of them from New York City. I loved how rapid and percussive New York speech was, and how alive it felt in my mouth when I was mimicking what I heard on the street. In New York, the sound of ordinary people talking was something like a communal stir fry—sizzling, fast, and spicy. In the South, speech stalled in my mouth—a lukewarm, overly sweetened, mushy pudding I didn’t care for. Linguistically, I committed to changing my diet.

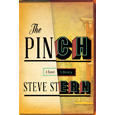

There were a lot of things that weren’t so great about the Columbia M.F.A. program thirty-five years ago, but its one surpassingly excellent attribute was location. On any given night, poetry readings worth going to were happening all over the city. Most were just a fifty-cent subway ride away. Thus it was that one evening in 1979 I gathered up a group of my new writer friends and planned an outing to the 92nd Street Y to hear a reading by Robert Penn Warren, who had just won his second Pulitzer Prize for poetry. A year earlier, back in Los Angeles, I had bought that book, Now and Then, when it first came out. I still have my copy, all marked-up and dog-eared, which begins with the ever-haunting line: “Beyond the last house, where home was….”

I insisted we go early enough to sit near the front, so we were in the second or third row when John Hollander walked out on the stage to introduce Warren. Finally, Warren himself approached the podium. He opened his mouth, and—it is not too dramatic to say—my whole identity as a writer shifted from one space to another. Here is how Warren began his reading on that unremarkable-until-then night in Manhattan:

Eye—uhd

Lahhk

Tuh Thah—ank

Maw Fur—rend—uh

Jaaaaw—uhn

Haul—un—duh

I’d like to thank my friend John Hollander. Those words, washed in the heat and blood of early-twentieth-century Southern speech patterns, stormed into me and have never left. The moment was an epiphany. Not an epiphany of sorts but an actual epiphanic moment of transformation that reframed my understanding of myself, who I was, where I was from, and to what extent I might change, revise, or refute that understanding. At the sibilant sounds of that old Kentucky accent, undiminished and still testifying to its origins after all Warren’s years at Yale, I was somehow undone. Something inside me, all coiled up and confused until then, began a long unraveling.

Warren went on talking, and a few seats down the aisle from me, one of my friends leaned over and whispered irritably in his own distinctive Brooklyn accent, “What the hell is he saying? I can’t understand a word!”

From out of the darkness and struggling through the traffic jam of neural transmitters crowding each other onto the limbic pathways leading to confusion, shock, dismay, and something that might be joy, one clear sentence made its way through: I think I might be a Southern poet./i> And I burst into tears.

Although many of the young writers I read and with whom I shared my work in the 1980s found Warren’s poems outdated or irrelevant, I was unable to stay away from them. Continually, I circled back until, almost without much conscious awareness, they became necessary to me: not just to me as a poet, but to me as a person. And not just as a person, but as a Southern person—a white Southerner who had more to learn than I could ever have imagined. If I thought I was learning how to write my own version of the long, loose, garrulous free-verse line that is so distinctive of Warren’s poetry (and that I longed to emulate), surely that was true. But as I studied and absorbed his expansive body of idiosyncratic poems, puzzled over their many voices, dissected their disconcerting rhetorical moves, and talked back to them, their metaphysics began to enter me as imperceptibly but perseverantly as the odor of a long-simmering stew eventually escapes the kitchen to infuse the entire house. Again and again, the poems pricked me into noticing the many privileges that my skin color had conferred—privileges available even to me, arising from the impoverished, uneducated, lower echelons of society.

In one of the first long poems of his that I loved, “Tale of Time,” again and again, I pored over section 7:

Planes pass in the night. I turn

To the right side if the beating

Of my own heart disturbs me.

The sound of water flowing is

An image of Time, and therefore

Truth is all and

Must be respected, and

On the other side of the mirror into which

At morning, you will stare, History

Gathers, condenses, crouches, breathes, waits. History

Stares forth at you through the eyes which

You think are the reflection of

Your own eyes in the mirror.

Ah, Monsieur du Miroir!

Your whole position must be reconsidered.

This was a poem that broke just about every “rule” I had made for myself in my first decade of writing seriously—overuse (and even capitalization of!) ridiculously huge abstractions; lines ending on prepositions; a wildly rhetorical (even oratorical) tone; and an almost complete lack of personal language. Why it stirred me so deeply was a mystery I kept returning to the way one returns to an exciting, on-again/off-again lover. And every time I reread it, the final line hit me sharply as a slap in the face.

Your whole position must be reconsidered.

When I look back on those early years of reading Warren, sometimes it seems to me that I went to his poems the way a person who loves puzzles and mind-ticklers might seek out the challenges of cryptic crosswords or double sudoku. I read them, slowly, repeatedly over the years, constantly asking myself (like any young poet), How did he do that? But even as I tried to teach myself something about how he put language on the page, the great questions of my own personal existence kept springing up to confront me. They distracted me with their harping queries: Who am I? Why am I here? Where have I come from? What is the right thing to do with my life? These were the awful self-interrogations I could not get away from as I kept on reading Robert Penn Warren.

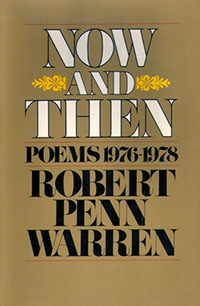

“How thin is the membrane between himself and the world,” he wrote in Audubon: A Vision:

He cannot bear what he sees.

He cannot think what guilt unmans him.

Why

Therefore, is truth the only thing that cannot

Be spoken?

And finally: In this century, and moment, of mania, / Tell me a story.

Through Warren’s poems I began to know myself—not just as a person with an individual reality and destiny, but as a citizen of a world far larger than myself and my concerns. His poems drew me out of the house and into the world. Of course, as soon as I stepped across the threshold onto the porch—and sometimes even before, still inside among family—personal identify became a problem. I might pat myself on the back sometimes for having descended from a long line of Southern poor whites who never owned slaves, but that was a cheap mind game. I knew from the attitudes and stories that had filtered down over the years that my people were no freer from racial prejudice, no less implicated in the ongoing oppression of black Southerners, than richer white people who had grown up among African-American cooks and cleaners, babysitters and gardeners.

For whatever reason, I had been given the opportunity to evolve out of the world that spawned me. Every book I read, every experience away from home, enlarged my perceptions and carried me farther away from my origins. Now Robert Penn Warren had widened the lens, forcing me to focus on the people I loved, including the fact that some of their attitudes and beliefs were abhorrent. This was a terrible struggle for me during my twenties. More than anything else, it was Warren’s poetry that helped me acquire the necessary psychic fortitude to look at the realities of the world I was born into. His poems forced me to ask myself (partly because of all the rhetorical questions he loved to include in his poems) how I was going to address those realities.

For whatever reason, I had been given the opportunity to evolve out of the world that spawned me. Every book I read, every experience away from home, enlarged my perceptions and carried me farther away from my origins. Now Robert Penn Warren had widened the lens, forcing me to focus on the people I loved, including the fact that some of their attitudes and beliefs were abhorrent. This was a terrible struggle for me during my twenties. More than anything else, it was Warren’s poetry that helped me acquire the necessary psychic fortitude to look at the realities of the world I was born into. His poems forced me to ask myself (partly because of all the rhetorical questions he loved to include in his poems) how I was going to address those realities.

We live in a different time now, but during my early years it seemed to me that most Southern whites practiced a kind of “polite” denial about the indefensible differences, the immoral gap between white lives and black lives. If you can’t say anything nice, Southern parents had a habit of telling their children, don’t say anything at all. This adage might be helpful for creating compliant offspring, but for writers denial constitutes the kiss of death.

“There is only one solution,” Warren’s poetry kept reminding me, nudging me closer and closer to topics I did not want to write about. “If/You would know how to live, here/Is the solution: … Your whole position must be reconsidered.”

Sometime during the early-1970s, I came across Warren’s nonfiction work from 1956, Segregation: The Inner Conflict in the South. I read it shuddering, standing up among the shelves of Alderman Library as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. Back then, it was all too real, and its bald, frank narratives conveying racial attitudes of black and white Southerners alike frightened the hell out of me. Documentary-style, it provided my first glimpse into the private thoughts and imaginings of black Southerners, my fellow citizens, people I had lived in shadowy proximity to for all my life.

I was stunned by the book’s revelations that forced me to confront the enormity of the gap between the preconceptions that my white upbringing had instilled in me and the evidence that Warren presented of the real lives of black people, described in their own voices. The shock was radical enough to create an opening that allowed me to take in brand-new thoughts: “For segregation has test steel into the Negro race and that is one valuable point of segregation,” an unnamed African-American minister said. It was an analysis that surprised me. In the parlance of that time, I could not get my (white, increasingly liberal) head around it. Continuing, he said:

It’s just foolish thinking for people to believe you can get the South to do in four or five years what they have been doing in the North for one hundred years. These people are emotional about their tradition, and you’ve got to have an educational program to change their way of thinking, and this will be a slow process.

The forgiving tone of his assertion was reassuring, but then he complicated his assessment by concluding on a more Darwinian note. A black man, he said, “has got to outthink the white man, has got to outlive the white man.” Comparing such complex, nuanced thinking to the stereotypes about African Americans with which I had been raised induced in me a now-familiar skin-shame. Twenty years old, I reshelved the book and walked away from it for more than a decade. I had a lot of living to do to catch up with that book.

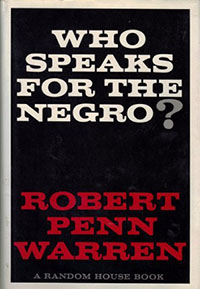

By 1989, when Warren died, I was on the faculty at Lousiana State University, where Warren himself had taught in the 1930s. A founding editor of The Southern Review, he was in many ways still alive there, so his death was felt very personally by the LSU community. Preparing to participate in the university’s memorial service for him, I thought to read some of the materials I had avoided until then. That is how Who Speaks for the Negro? first came into my life.

In that book, Warren’s nonfiction writings on segregation and race relations reached their culmination. Although mostly a compilation of interviews with African Americans working in the civil-rights movement (including MLK and Malcolm X, Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young), the book includes passages of Warren’s personal ruminations on race, as well. I can still remember the relief of reading his words as he revisited, for the first time, his own deeply troubling essay defending segregation in I’ll Take My Stand, published in 1932 when he was only twenty-seven. “I never read that essay after it was published,” he wrote more than thirty years later in Who Speaks for the Negro?, “and the reason was, I presume, that reading it would, I dimly sensed, make me uncomfortable.”

Even as he was writing it, he recalled, something about his own position unsettled him:

I had experienced some vague discomfort, like the discomfort you feel when your poem doesn’t quite come off, when you’ve had to fake, or twist, or pad it, when you haven’t really explored the impulse. … [E]ven then, thirty-five years ago, I uncomfortably suspected, despite the then prevailing attitude of the Supreme Court and of the overwhelming majority of the population of the United States, that no segregation was, in the end, humane.

And then this extraordinary confession emerged: “It never crossed my mind that anybody could do anything about it.”

Dear God, I remember thinking: if it had never crossed the mind of the young genius Robert Penn Warren that “anybody could do anything” about the tragedy of segregation, perhaps it might be possible to admit my own shortcomings and conflicts. Maybe then I could make some progress as a person, as well as a poet.

Of course, within the context of his literary genius, Warren was one of the few Southern writers of his generation who did “do something” about what he called the inner conflict that characterized and deformed all life, white and black, in the region where he was born in 1905. There were other white Southern writers who pulled polite veil after polite veil from the white Southern psyche, revealing the immorality of and mutual damage inflicted by segregation—Peter Taylor, Harper Lee, Erskine Caldwell, Flannery O’Connor. But I don’t believe there was anyone besides Warren who had the moral rectitude to recant his own earlier work, or the courage to dissect in public the uglier, less evolved statements that were part of some of his earlier work. There was certainly no other Southern poet of his time who did so, and his example made all the difference to me.

Of course, within the context of his literary genius, Warren was one of the few Southern writers of his generation who did “do something” about what he called the inner conflict that characterized and deformed all life, white and black, in the region where he was born in 1905. There were other white Southern writers who pulled polite veil after polite veil from the white Southern psyche, revealing the immorality of and mutual damage inflicted by segregation—Peter Taylor, Harper Lee, Erskine Caldwell, Flannery O’Connor. But I don’t believe there was anyone besides Warren who had the moral rectitude to recant his own earlier work, or the courage to dissect in public the uglier, less evolved statements that were part of some of his earlier work. There was certainly no other Southern poet of his time who did so, and his example made all the difference to me.

No wonder I wept when I first came into his presence at twenty-five years old, in New York City, in full, unconscious flight—until that moment—from my freighted, unwanted identity as a Southern writer.

In a women’s support group I attend, one of the commitments we make to ourselves and to each other is to “get clean.” By “clean,” we mean a kind of emotional honesty, first with ourselves and then with others. We mean: as much integrity as we can summon in any given moment, taking into consideration our all-too-human limitations, and our conscious acceptance not only of our own shortcomings and failures, but those of others, as well. We mean: not avoiding the hard thing just because it is hard or might displease someone else. When one has been raised without those habits, they are hard practices to develop.

Robert Penn Warren helped white Southern literature understand the importance of getting clean– or, at least, he helped later generations of white writers born in the South understand the moral necessity of trying to get clean, and to live that way, regardless of the filthy wickedness of our shared past, and in spite of the heavy burden of trying to change. Warren began to seem to me—as he has come to be regarded by so many—a rare white Southerner of conscience and moral courage who devoted his prodigious abilities and his expansive consciousness not just to poetry, but to the moral development of Americans—especially of Americans of the South. I have always thought he should have received the Nobel Prize for literature.

All these years later, the poetry of Robert Penn Warren is part of my bedrock. I read and re-read it, quote it to myself in necessary moments, teach it, and probably proselytize about its healing brilliances. In my head, I hear his iconic voice when I want to, or need to—a set of sounds that unfastens from the present and reattaches me to some aspect of the past that I hadn’t known I was in need of. For me, Warren’s voice is the sound of a home I never realized I had until I heard him. And his poetry is the evidence of what a hard place it has been to call home, and how necessary it still is to grapple with its challenges.

As a young writer, I needed Warren’s poetic demand that I undertake, as a Southerner, the hard thing not just for my personal benefit, but in order to live among others with a clean conscience and a raised head. Now, in my sixties, I require the sustaining, dynamic example of his work over time. More than any other writer who is personally important to me, Robert Penn Warren understood, I think, what it really means to live in time, to admit that we are powerless over time. That was one of his great subjects.

I find myself quite often these days thinking of how his remarkable intellect and his extraordinary humanity might have been stimulated by our own era of radical realignments of racial paradigms, moving rapidly from a white majority to a society in which people of color are the larger cohort. Every day, it seems to me, the old questions of race and identity become increasingly outmoded, replaced by new complexities that seek their own original articulations of this moment in time. We are all still working it out. I can’t guess what kind of work Robert Penn Warren might have made from present opportunities, but I am confident that he would not have evaded engagement with the present moment, fractious and uncertain as it is. After all, he is the one who wrote these words at the end of All the King’s Men and offered them to all of us: “[S]oon now we shall go out of the house and go into the convulsion of the world, out of history into history and the awful responsibility of Time.”

Poet Kate Daniels, a professor of English, directs the creative-writing program at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Her most recent book is A Walk in Victoria’s Secret.

This essay is part of the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prize board and the Federation of State Humanities Council in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. For their generous support of the Campfires Initiative, we thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes board, and Columbia University.