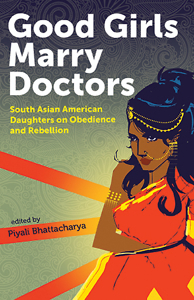

Beyond “Good Girls”

In a new anthology, South Asian American daughters construct their own identities

Moments before she submitted the final manuscript of Good Girls Marry Doctors, Nashville-based editor Piyali Bhattacharya cried. She cried, partly because she was overwhelmed by the courage of the South Asian American women who shared their stories despite the risk of painting their parents in a less-than-flattering light. “Good Girls marry doctors, it’s true, especially in the Desi community,” she writes in the anthology’s introduction. “What, then, do Bad Girls do? Surely, I reasoned in that moment, Bad Girls write publicly about their parents and guardians. Bad Girls take all the sacrifices their immigrant parents made for them … and twist them into perverted abuses.”

Yet within these twenty-six essays, the truth never seems twisted. Rather, Good Girls Marry Doctors deconstructs the very idea of “good girls” and “bad girls,” revealing instead dozens of powerful storytellers. These essays are more than exercises in vulnerability. They’re smart and honest and open, sometimes tragic and sometimes funny in their examination of what happens when women and girls pursue their own dreams at the risk of undermining cultural expectations and disappointing their parents. Along with the risks involved in taking any new path, they also risk losing their sense of self: “Without the approval of our parents, how would we pin down and draw out the maps of our bodies, our spirits?” Bhattacharya asks.

Yet within these twenty-six essays, the truth never seems twisted. Rather, Good Girls Marry Doctors deconstructs the very idea of “good girls” and “bad girls,” revealing instead dozens of powerful storytellers. These essays are more than exercises in vulnerability. They’re smart and honest and open, sometimes tragic and sometimes funny in their examination of what happens when women and girls pursue their own dreams at the risk of undermining cultural expectations and disappointing their parents. Along with the risks involved in taking any new path, they also risk losing their sense of self: “Without the approval of our parents, how would we pin down and draw out the maps of our bodies, our spirits?” Bhattacharya asks.

Good Girls Marry Doctors might be seen as an effort to draw out that map. The essays prove both cathartic and cartographic in their ability to chart the way these writers negotiate the complex multitude of worlds they inhabit as daughters, mothers, sisters, immigrants, children of immigrants, scholars, and artists. In “The Cost of Grief,” Tanzila Ahmed finds herself unsure of what to do or say in the Muslim graveyard at her mother’s funeral—because usually her mother would be there to guide her through the customs. In “Patti Smith in the Dark,” Jyothi Natarajan is forced into the role of mediator between her sister, who identifies as queer, and her parents, who for years read her sister’s queerness as a childish rebellion.

Sometimes stereotypes about what South Asian parents would and would not support are what these writers must fight against. In “Acting the Part,” Rachna Khatau finds herself constantly working to convince other Indian Americans her own age that her parents are in fact proud of her decision to be an actor—the assumption being that no Indian parents would ever support a career in the arts. Bhattacharya’s own essay in the collection showcases what happens when the world of social media collides with familial judgment: “Piyali,” Bhattacharya’s mother emails, “I saw your latest Facebook post, and I’m writing to tell you that it wasn’t appropriate.”

Sometimes stereotypes about what South Asian parents would and would not support are what these writers must fight against. In “Acting the Part,” Rachna Khatau finds herself constantly working to convince other Indian Americans her own age that her parents are in fact proud of her decision to be an actor—the assumption being that no Indian parents would ever support a career in the arts. Bhattacharya’s own essay in the collection showcases what happens when the world of social media collides with familial judgment: “Piyali,” Bhattacharya’s mother emails, “I saw your latest Facebook post, and I’m writing to tell you that it wasn’t appropriate.”

One of this anthology’s major strengths is the space it makes for the specific experiences of its individual authors without forcing them to fit into a uniform vision. Still, there are questions that multiple authors wind up addressing. In “Good Girls Pray to God,” Triveni Gandhi spends time in India to help her reconnect to her younger self, but her sense of identity begins to seem even more ruptured: “If I could be one person in America, and another in India, then who was I really?” she asks. “Where did my faith actually lie, and what did my different actions and beliefs in varying contexts really say about who I was?”

While these exact questions don’t serve as the guiding thread for every essay in the anthology, each writer does examine the way a sense of identity and family can rupture, heal, or become more complicated, especially in relation to larger communities. Nayomi Munaweera’s powerful “The Only Dates Are The Ones You Eat: and Other Laws of an Immigrant Girlhood” considers what it means to accept your own story in the midst of this complication: “Even now at forty-one, it can be hard to claim my own narrative. Yet I am learning over and over that how the community views you, how anyone views you from outside the sanctity of your own skin, is a sad substitute for the power that can be gained from inhabiting your own story and your own sexuality.”

Several authors in Good Girls Marry Doctors inhabit their own stories by putting their essays in dialogue with other stories. “Modern Mythologies” by Surya Kundu interweaves Kundu’s experience of moving toward independence with the story of Sita, who is exiled, abducted by Ravana, and who, once rescued, must go through many tests and trials to prove her purity to Prince Rama. “I choose my own culture,” Kundu concludes, “not out of obligation or fear, but as it can be redefined by me.”

SJ Sindu does not just redefine but seeks to rewrite: In “Draupadi Walks Alone At Night,” Sindu borrows from the narrative epic The Mahabharata to rethink Draupadi, who is forced to marry five brothers and suffers in exile. Sindu’s own parents refuse to accept her bisexuality, consulting experts in past lives, mystics, and astrologists to determine why their daughter is not yet married. Sindu takes her anger and casts it back to Draupadi’s narrative: “Draupadi, I want to rewrite your story. … I want your rage to cut through everything and spin the world into new string. … I want to inherit your anger and use your string to stitch my two selves back together.”

Rewriting, redefining: these acts allow the authors of Good Girls Marry Doctors to speak back to stories from the past—whether these stories come from the legends of a culture or from family histories. And speaking to the past allows many of them to speak, too, to the girls who will need a book like this in the future. “For the women who have written for it, this book represents the breaking of a long and deep silence,” Bhattacharya writes. “It is the book we wished we’d had when we were going through our darkest moments.” By mapping their own experiences, by redefining themselves, the writers of Good Girls Marry Doctors may also help illuminate paths for their readers that previously seemed impossible to navigate.

Lee Conell’s fiction has won the Chicago Tribune’s Nelson Algren Award and appeared in places like Kenyon Review, Guernica, Glimmer Train, and American Short Fiction. She earned her M.F.A. at Vanderbilt University and lives in Nashville.