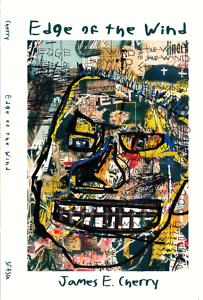

Poetry at Gunpoint

The new novel by James E. Cherry is a thriller with the soul of poetry

The list of literary greats whose work has celebrated and explored the link between jazz improvisation and verbal expressiveness extends from Phillip Larkin to Amiri Baraka, Langston Hughes to Jayne Cortez, Sonia Sanchez to Gil Scott-Heron. While different in key technical areas, there’s certainly a resemblance between the spontaneous creation that occurs during the writing of a poem and the evolutionary process of a jazz composition. In a compelling and disturbing new novel, Jackson, Tennessee, poet James E. Cherry explores that link.

Set in a contemporary West Tennessee town not far from Memphis, Edge of the Wind tells the gripping tale of a brilliant, mentally ill poet named Alexander van der Pool, whose search for fulfillment and salvation is centered on the quest to write a perfect poem. Van der Pool’s turbulent past, which includes incidents of domestic and personal violence, as well as difficult parental and sibling relationships, gets folded into the ongoing story, which takes a grim turn when he takes a poetry class hostage at the local junior college.

Set in a contemporary West Tennessee town not far from Memphis, Edge of the Wind tells the gripping tale of a brilliant, mentally ill poet named Alexander van der Pool, whose search for fulfillment and salvation is centered on the quest to write a perfect poem. Van der Pool’s turbulent past, which includes incidents of domestic and personal violence, as well as difficult parental and sibling relationships, gets folded into the ongoing story, which takes a grim turn when he takes a poetry class hostage at the local junior college.

Besides being obsessed with poetry and jazz, van der Pool is a schizophrenic who has stopped taking his medication. Even before he strolls into the classroom and imprisons several individuals there, he’s carrying on a running conversation with a previously subdued inner voice. That voice alternately praises and discourages, scolds and counsels:

“Alright van der Pool,” Tobi said. “You got everybody sitting around like you are a bunch of Chinese flowers. We gone meditate or what? You better watch that motherfucker with the afro. He reminds me a lot of some of them niggers I used to hang out with at the pool hall…. If you ever wanted a captive audience, Van der Pool, I don’t think you’ll beat this group.”

As the story unfolds, van der Pool engages with a diverse cast of characters that includes a generally sympathetic (though frightened) teacher, a would-be blues singer wrestling with his own issues of identity and authenticity (he’s a white artist operating in a black art form), an elderly woman recovering from chemotherapy, a pregnant woman whose mate is serving overseas in the military, and a prospective college baseball player, among others.

The dynamic of race fuels this story. Van der Pool’s rage—and, arguably, his mental illness—are driven by his anger at the kind of continual inequality that’s a direct product of systemic racism. He feels his battle for poetic success has been undercut by racism in a world where being black automatically puts him behind a white person with the same exact goals and life experiences:

“First this white boy and the blues and now this white woman and black history. You know you in trouble when white folks start explaining who you are, what you do, and why you do it. Next thing you know, they’ll have you believing you’re a fucking Chinese. Matter of fact, I think Meagan and Tennessee Red might be communists, too. Why do you think they call him Red? And another thing; they ain’t got no black folk that can teach black poetry?”

The poetry class is no random hostage situation: these young writers are doing what van der Pool himself has always wanted—to learn about poetry and become a successful poet—but now will never be able to do because of this explosive act. Cherry nicely weaves the hostages’ disparate stories and perspectives into the increasingly dramatic narrative, with each character trying to manage this dangerous situation and also to serve as critic and adviser to van der Pool, who offers running examples of his own poems at gun point.

Outside the classroom, there’s a clash between the local sheriff, anxious to handle the situation with minimum fanfare and casualties, and state and federal authorities upset because they feel a nutcase is making everybody look ineffective in front of national media outlets. The situation degenerates as certain characters make a bad situation worse by exercising a power they should never have been given in the first place.

Outside the classroom, there’s a clash between the local sheriff, anxious to handle the situation with minimum fanfare and casualties, and state and federal authorities upset because they feel a nutcase is making everybody look ineffective in front of national media outlets. The situation degenerates as certain characters make a bad situation worse by exercising a power they should never have been given in the first place.

Though sometimes frenetic, the pace of the narrative grows more relaxed when necessary. Cherry’s prose expertly depicts a poet’s mind at work, even when van der Pool’s mental illness affects his struggle to pick the right word, set a mood, or deliver coherent statements. Throughout the novel, Cherry occasionally interjects reflections on other issues, including gentrification, immigration, cultural appropriation, police brutality, and even fishing and hunting.

Edge of the Wind not only spotlights the connection between poetry and jazz but continually peels back the curtain that too often obscures the way racial injustice still affects so many people. And Cherry manages this feat without sacrificing the edginess and punch needed for a first-rate thriller. Edge of the Wind is a treat for lovers of poetry, jazz, and suspense.

Ron Wynn is a music critic, author, and editor. His work has appeared in the Nashville Scene, the Tennessee Tribune, the Memphis Commercial Appeal, and Jazz Times, among many others. He lives in Nashville.

Ron Wynn is a music critic, author, and editor. His work has appeared in the Nashville Scene, the Tennessee Tribune, the Memphis Commercial Appeal, and Jazz Times, among many others. He lives in Nashville.