Without Spin

R.A. Dickey, Nashville native and New York Mets knuckleballer, has written a redemption narrative that spares no detail about why he needed to be redeemed

To throw a knuckleball well, a pitcher must unlearn almost everything he knows. A knuckleball demands the opposite of conventional pitching: it forces the pitcher to relinquish control, so that the pitch, which leaves his hand with zero rotation, is at the mercy of the elements. A good knuckleball looks like a whiffleball butterflying through a gust of wind. This is both the power and the drawback of the pitch: it is, in a game whose very essence is predictability, wildly unpredictable.

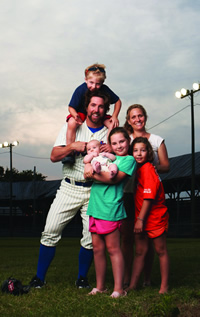

For R.A. Dickey—a Nashville native who played for Montgomery Bell Academy and the University of Tennessee and is now the number-two starter for the New York Mets—throwing the knuckleball also makes an apt metaphor for life: instead of imposing one’s will, as a pitcher must when he throws a curve or a slider or any other pitch, the knuckleballer relies on faith. Having done what he can to prepare (years of practice, wind-up, release, follow-through), he leaves the results to a higher power (physics, God).

In his new memoir, Wherever I Wind Up: My Quest for Truth, Authenticity and the Perfect Knuckleball (written with New York Daily News sportswriter Wayne Coffey), Dickey recounts his struggle to make it in the major leagues, achieving real success only after he transformed himself from a conventional pitcher into a knuckleballer. In the book, Dickey parallels that story with his real subject: how finally confronting his childhood traumas, including sexual molestation, freed him from self-centeredness and shame. For Dickey, mastering the knuckleball went hand in hand with mastering his own demons: once he gave up control, he began to succeed.

In 1996, Dickey, a heat-throwing phenom from UT and a starter on the U.S. Olympic team, was drafted in the first round by the Texas Rangers. His future as a fireballer seemed assured. But then the Rangers, who had initially offered Dickey a signing bonus of close to a million dollars, rescinded their offer after a medical exam revealed that Dickey has no ulnar collateral ligament in his pitching arm. Unwilling to invest so much in what appeared to be a medical freak of nature (no one can explain how Dickey has been able to pitch without a UCL), the Rangers dropped their offer to $75,000. Dickey was distraught: “I can pitch. I can compete as hard as anyone you’ve ever seen,” Dickey imagined saying to the ballclub. “That’s why you made me the eighteenth pick in the whole stinkin’ draft. Don’t you remember that? Don’t you know how much more important what I have inside me is than a little laxity in the elbow?”

In 1996, Dickey, a heat-throwing phenom from UT and a starter on the U.S. Olympic team, was drafted in the first round by the Texas Rangers. His future as a fireballer seemed assured. But then the Rangers, who had initially offered Dickey a signing bonus of close to a million dollars, rescinded their offer after a medical exam revealed that Dickey has no ulnar collateral ligament in his pitching arm. Unwilling to invest so much in what appeared to be a medical freak of nature (no one can explain how Dickey has been able to pitch without a UCL), the Rangers dropped their offer to $75,000. Dickey was distraught: “I can pitch. I can compete as hard as anyone you’ve ever seen,” Dickey imagined saying to the ballclub. “That’s why you made me the eighteenth pick in the whole stinkin’ draft. Don’t you remember that? Don’t you know how much more important what I have inside me is than a little laxity in the elbow?”

Still, he took the deal, and within a couple years, as he expected, Dickey had reached the Triple-A level, one step away from the big leagues. After that, though, he languished for the next dozen or so years, making it up to The Show from time to time but never sticking there. When he was sent back down to the minors again in 2005, Rangers manager Buck Showalter and pitching coach Orel Hershiser gave Dickey some advice: at thirty, they said, his last and only hope of making it back to the majors was to learn to throw a knuckleball. “You become a knuckleball pitcher when you hit a dead end, when your arm gets hurt, or your hard stuff isn’t getting the job done,” Dickey writes. Wary at first, he eventually embraced the idea and—with years of practice and help from knuckleball legends Charlie Hough, Phil Niekro, and Tim Wakefield—mastered the pitch. Since the middle of the 2010 season, Dickey has been an integral part of the Mets rotation.

But that Rocky-like narrative serves mostly as an excuse for Dickey to write about what really concerns him: how he overcame the devastating psychological consequences that resulted from two episodes of childhood sexual molestation. The first happened when he was eight, and his thirteen-year-old babysitter forced him to perform sexual acts on her over the course of several babysitting sessions. The second happened when he was nine and involved a teenage boy. While Dickey goes into some detail regarding the babysitting molestations, he holds back the details involving the older boy. In fact, it is relatively late in the book when he explains how traumatic the event was for him, and how the shame from it contributed to boorish behavior that jeopardized his marriage and his ability to be a good father.

But that Rocky-like narrative serves mostly as an excuse for Dickey to write about what really concerns him: how he overcame the devastating psychological consequences that resulted from two episodes of childhood sexual molestation. The first happened when he was eight, and his thirteen-year-old babysitter forced him to perform sexual acts on her over the course of several babysitting sessions. The second happened when he was nine and involved a teenage boy. While Dickey goes into some detail regarding the babysitting molestations, he holds back the details involving the older boy. In fact, it is relatively late in the book when he explains how traumatic the event was for him, and how the shame from it contributed to boorish behavior that jeopardized his marriage and his ability to be a good father.

The defining moment came after Dickey’s unsuccessful attempt to swim the Missouri River (which he calls “one in a long line of unfathomably stupid risks I’ve taken”) while in Council Bluffs, Iowa, as a member of the Nashville Sounds. Already depressed about his career and life in general, Dickey staged the crossing as a stunt, and his teammates wagered on whether he could make it across. Looking at the river from an upper floor of the team’s hotel, Dickey thinks, “Maybe if I somehow get across, swim like a madman through the turbidity, God will help me close the prodigious gap between the man I am and the man I want to be.”

But the Missouri is more river than Dickey bargained for, and when he was about halfway across, things began to look bleak: “I am sinking fast now, well below the surface. I am ready to die, and as I spend the final moments of my life engulfed in sorrow and regret, I feel solid ground. … I have hit bottom. Literally.”

Pushing off from the bottom, Dickey eventually made it to shore, an event he credits to divine intervention: “I jumped in the water thinking I was in charge,” he writes. “I found out He was in charge.” After this emotional turning point, Dickey’s knuckleball kicked in, too, propelling him into the majors for good. Assuming, as most baseball people do, that the Mets’ number-one starter, Johan Santana, will be traded before the year is out, Dickey is in line to become the ace of the staff. A decade and a half after signing as a flamethrower, Dickey finally made it as a knuckleballer.

Pushing off from the bottom, Dickey eventually made it to shore, an event he credits to divine intervention: “I jumped in the water thinking I was in charge,” he writes. “I found out He was in charge.” After this emotional turning point, Dickey’s knuckleball kicked in, too, propelling him into the majors for good. Assuming, as most baseball people do, that the Mets’ number-one starter, Johan Santana, will be traded before the year is out, Dickey is in line to become the ace of the staff. A decade and a half after signing as a flamethrower, Dickey finally made it as a knuckleballer.

At thirty-seven, Dickey is now in the prime of his career. Because the pitch exacts little wear on the arm, knuckleballers can pitch well into their forties. But once he does retire, Dickey, who majored in English literature at UT and was an Academic All-American, may well pursue a writing career. He has been encouraged in his writing by the likes of New York Times sports columnist George Vecsey, and Sports Illustrated called Wherever I Wind Up the best book by a major leaguer since Jim Bouton’s classic Ball Four.

Typically, when ballplayers write books, they are of the tell-all variety, a la Jose Canseco. It is rare to find a baseball book by an insider that dishes no dirt, criticizes no one (except for a couple of shots at Alex Rodriguez, which seems almost obligatory), and offers nothing but praise for almost every human being it mentions. It is even rarer to find a professional athlete willing to acknowledge his own victimization and the severe psychological problems it caused. In Wherever I Wind Up, R.A. Dickey reveals himself to be a sensitive, fragile human being—just like the rest of us.

R.A. Dickey will discuss Wherever I Wind Up: My Quest for Truth, Authenticity and the Perfect Knuckleball on April 12 at Franklin’s LifeWay Christian Store at 4 p.m. and at Nashville’s Books-A-Million at 7:30 p.m.