A Park is Born

Following the success of last year’s Smoky Jack, Ken Wise and Anne Bridges revive another memoir by Paul J. Adams

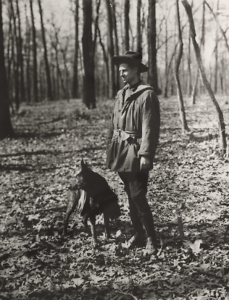

In 1925 Paul Adams, a twenty-four-year-old naturalist who might have popped whole from a Jack London novel, left his home in Knoxville to live alone on Mount Le Conte, the highest peak in what would become the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. There he and a smart German Shepherd named Jack established the first permanent lodge. Adams recorded their adventures in a journal later discovered by Anne Bridges and Ken Wise, co-directors of the Great Smoky Mountains Regional Project at the University of Tennessee libraries, who edited them into a surprisingly readable adventure story published last year as Smoky Jack. The pair have now edited and supplemented a related book, long out of print: Mount Le Conte, a memoir that Adams self-published in 1966, four decades after the events he related in the journals that became Smoky Jack.

In the first chapter of Mount Le Conte, the older Adams describes the mountain that dominated much of his life, employing the same mixture of simple facts and eloquent observation that marked his early journals:

Le Conte is most often viewed from the west. On that side it rises from a base level of about 1,200 feet to 6,593 feet in a lateral distance of about four miles. So it looms as a very prominent mountain. From Knoxville, on clear days one can see it standing out in front of the main range like a great sore thumb. It is a massive upheaval, clothed in many different shades of green at different times of the year and even at the same time.

The ten short chapters of this short book chronicle key events in the early history of the conservation association, the construction of what would become LeConte Lodge, and the establishment of what remains the country’s most-visited national park. While a few events in Mount Le Conte are also depicted in Smoky Jack, the book focuses more on history than narrative—by the mid-1960s, he had become well aware of the importance of recording for history events that, in his twenties, had been merely his own daily observations. This is not to suggest that Mount Le Conte lacks narrative: the chapters “Squirrel Jello” and “Fire Watching,” for example, contain the same sort of humorous anecdotes that pepper Smoky Jack.

But in editing the book with an eye to the national park’s early history, Wise and Bridges have transformed this all-but-forgotten self-published pamphlet into a fitting companion to Smoky Jack. Their contribution takes several forms: relevant photographs from various collections, sketches from Adams’s journals, newly drawn maps, explanatory footnotes, and—perhaps most helpfully—a thorough introduction, which not only gives the broad strokes of Adams’s biography but also reconciles what would otherwise appear to be inconsistencies between the two books.

But in editing the book with an eye to the national park’s early history, Wise and Bridges have transformed this all-but-forgotten self-published pamphlet into a fitting companion to Smoky Jack. Their contribution takes several forms: relevant photographs from various collections, sketches from Adams’s journals, newly drawn maps, explanatory footnotes, and—perhaps most helpfully—a thorough introduction, which not only gives the broad strokes of Adams’s biography but also reconciles what would otherwise appear to be inconsistencies between the two books.

Wise and Bridges explain, for example, that the mountain itself was named after a professor John Le Conte from South Carolina College (later the University of South Carolina), with a space between “Le” and “Conte.” Nevertheless, from its earliest days the lodge that grew from Adams’s early camp was called “LeConte” with no space—the name by which it goes today. Likewise, the title character of Smoky Jack, one of the most unforgettable dogs to be described in print in recent years, goes by the name of Cumberland Jack in this book. The reason, it turns out, is that “Cumberland” was part of the lengthy actual name as it appeared on the dog’s pedigree—Adams had simply nicknamed him “Smoky” during their sojourn on the mountain.

In May 1926, the conservation association suddenly replaced Adams with Jack Huff, who would run the LeConte Lodge for the next thirty-five years. In their introduction, the editors attempt to sleuth out the never-revealed reasons for the abrupt change in personnel—a question left hanging at the end of Smoky Jack. As careful historians, they emphasize that “it is only possible to speculate” about the reason for Adams’s dismissal, but their case is compelling.

As this memoir explains, the role Adams played in establishing the lodge may have ended in 1926, but his relationship with the mountain only grew. During the four decades following 1926, he writes, there “have been few years” in which he did not ascend Mount Le Conte to enjoy “visiting the dark forest of spruce and balsams, hearing the call of the veery and winter wren, seeing again the delicate beauty of sand myrtle blossoms and the splendor of sunrises and sunsets from Myrtle Point and Cliff Top.” Le Conte, Adams explains, is “something special—even in an area so outstanding as the Great Smokies.”

For readers and modern hikers alike, Adams proves an excellent guide.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a recent textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.