American Letters

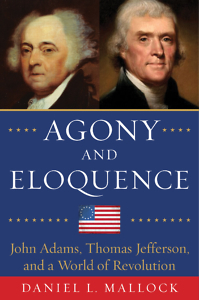

Daniel L. Mallock finds timely lessons in the friendship of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“You and I ought not to die before we have explained ourselves to each other.” These are the words of John Adams—founding father, first vice president, and second president of the United States. They were addressed to Thomas Jefferson—founding father, second vice president, and third president of the United States. Adams and Jefferson were mending a friendship interrupted by disagreements over the French Revolution and the rancor of American party politics. As Nashville author Daniel L. Mallock explains in Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and a World of Revolution, the two men “set a pattern of understanding, acceptance, and forgiveness that ranks their letters as a monument to human compassion and grace.”

“You and I ought not to die before we have explained ourselves to each other.” These are the words of John Adams—founding father, first vice president, and second president of the United States. They were addressed to Thomas Jefferson—founding father, second vice president, and third president of the United States. Adams and Jefferson were mending a friendship interrupted by disagreements over the French Revolution and the rancor of American party politics. As Nashville author Daniel L. Mallock explains in Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and a World of Revolution, the two men “set a pattern of understanding, acceptance, and forgiveness that ranks their letters as a monument to human compassion and grace.”

The friendship between Adams and Jefferson was an unlikely one. Adams was a devoutly religious, anti-slavery, naturally conservative Yankee. Jefferson was a skeptic, a slave-holder, and a radically revolutionary Southerner. Yet when they met while serving the colonies during the Second Continental Congress, their brilliant minds recognized in each other a fellow traveler. They became best friends, a relationship that included their families and lasted through the American Revolution, their postings as ambassadors to France and Great Britain, and even during the early years of government under the Constitution, when Vice President Adams and Secretary of State Jefferson served President George Washington.

But their friendship foundered on the rocks of another revolution, one that nearly wrecked the nation that Adams and Jefferson had struggled so hard to create. In 1789, French citizens stormed the Bastille in Paris, the opening move in what became one of the bloodiest revolutions in history. Jefferson, who believed that the violence was a necessary cleansing of the old and part of the natural progress of republicanism, returned from his mission to France to find Washington, Adams, and other leading politicians deeply worried. These Federalists feared that the French violence would infect the rest of Europe and threaten the United States, which it did by the time Adams won the presidency. “The winds that once swept from America to Europe in the exciting and dark days of 1776,” Mallock writes, “would return in a cold, bitter rush during the presidency of Jefferson’s friend, John Adams.”

Jefferson, leader of the Democratic-Republicans, reluctantly became Adams’s vice president, as was then required of the second-place candidate for president. Jefferson wanted to assist his revolutionary friends in France and took a remarkably contrary position to that of President Adams, going so far as to engage in unauthorized communications with French officials. Their philosophical differences and Jefferson’s behind-the-scenes machinations, Mallock notes, “set Adams on a completely divergent path both politically and personally from Jefferson.”

By 1801, when Jefferson became president and Adams departed Washington the night before the inauguration, the break between the former best friends seemed complete. So fraught was the relationship that even a note of condolence sent to Jefferson by Abigail Adams on the death of one of his daughters turned into a short and bitter exchange full of recriminations. The two men did not communicate with one another for almost a decade, and it appeared they never would again.

Enter Dr. Benjamin Rush, a distinguished physician, member of the Second Continental Congress, and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Rush maintained a close friendship with both Adams and Jefferson for his entire life and by 1810 was ready to see his old compatriots reunited. He viewed the two former presidents as “the North and South Poles of the American Revolution,” and with a series of cleverly crafted letters to both men convinced them that they really did still care for each other and want to explain themselves.

Enter Dr. Benjamin Rush, a distinguished physician, member of the Second Continental Congress, and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Rush maintained a close friendship with both Adams and Jefferson for his entire life and by 1810 was ready to see his old compatriots reunited. He viewed the two former presidents as “the North and South Poles of the American Revolution,” and with a series of cleverly crafted letters to both men convinced them that they really did still care for each other and want to explain themselves.

In early 1812, letters began passing between Jefferson’s Monticello and Adams’s Peacefield. Once begun there was no stopping the outpouring of affection and intellectual reconnection. The exchange, which Mallock describes as “a landmark achievement in American letters,” ended only with their near simultaneous deaths on July 4, 1826.

Agony and Eloquence, Mallock’s first book, succeeds in shining a timely light on a relationship that exemplifies what is wrong and right with the American political system. Jefferson and Adams participated in party politics as a necessity, but both despised the divisions the parties created, believing them to be a danger to the nation. Mallock makes it clear that the current state of American politics is exactly what Adams and Jefferson feared would happen if party affiliation divided friends and neighbors.

In overcoming their animosity and returning their relationship to the mutual respect and admiration they had enjoyed for so many years before the birth of the two-party system, Adams and Jefferson led by example. Mallock concludes, “Let us hope that the lessons of these men find their way to the core of our democracy so that the habits of personal relationships are not overturned by the passions of political differences.”

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than twenty-five years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and a historian by avocation.