A Vast Cacophony of Contradictions

Photographer Jack Spencer seeks the soul of a country

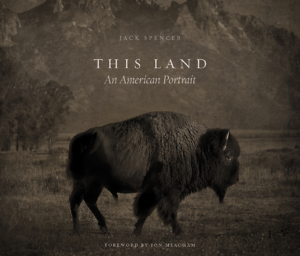

In his introduction to This Land: An American Portrait, photographer Jack Spencer writes, “I have an idea of America as a vast cacophony of contradictions,” and this new collection of Spencer’s photos bears that description out. Strikingly beautiful landscape and wildlife shots share these pages with unsettling images of power plants and empty factories. But there’s an imaginative coherence in Spencer’s vision that overwhelms the dissonance. Regardless of his subject, he is able to capture a beauty rich in possibility, and though some—perhaps most—of his images are poignant to a degree, they never seem to dwell in sorrow. Spencer’s America is exquisitely alive and protean.

In 2003, national fervor for the recently launched Iraq War was running high, and Spencer was deeply disturbed, he writes, by the “flag-waving vitriol.” He embarked on a cross-country road trip “in hopes of making a few ‘sketches’ of America in order to gain some clarity on what it meant to be living in this nation at this moment in time.” That journey evolved into a thirteen-year project to create the collection that makes up This Land. There are images here from every region of the country, and many of the subjects are iconic: the Tetons and the Yellowstone River, buffalo and wild mustangs, the Jefferson Memorial and Mount Rushmore. But Spencer often turns to quieter, less familiar scenes, too, including an unremarkable intersection in Lost Nation, Iowa, and an anonymous, leaf-strewn clearing somewhere in Nashville, Tennessee.

Spencer describes himself as “a pictorialist at heart,” having “only slight regard for what the machine itself records.” While the pictures here are realistic, they’re manipulated with a painterly sensibility that evokes Spencer’s acknowledged influences: Rothko, Bierstadt, and Hopper. Heavily saturated color and soft focus render a dreamy quality to subjects as simple as a fence line across the Montana prairie and clouds reflected on the surface of the Snake River. Spencer is partial to fog, and he has a genius for letting it do its mystical work in otherwise stark images of coastlines and prairie. In a picture taken at Point Reyes, California, fog rests gently on a grove of wind-bent trees like a blanket on a sleeping giant, and wild horses on Cumberland Island, Georgia, become eerie shadows behind heavy mist.

Some of the pictures taken early in the project were meant to reflect Spencer’s anger over the war. He distressed the prints by bending and burning them, and the resulting images, particularly one of a tattered U.S. flag at Wounded Knee, convey a kind of desolate alienation. They are nevertheless beautiful, endowed with the same revelatory light that marks the entire collection. Over the course of the project, Spencer moved past anger to a deeper, more complex response to the American scene, one that included simple joy. His western landscapes are genuinely breathtaking, and he depicts the lush charm of Cumberland Island with what seems like un-ironic wonder.

Some of the pictures taken early in the project were meant to reflect Spencer’s anger over the war. He distressed the prints by bending and burning them, and the resulting images, particularly one of a tattered U.S. flag at Wounded Knee, convey a kind of desolate alienation. They are nevertheless beautiful, endowed with the same revelatory light that marks the entire collection. Over the course of the project, Spencer moved past anger to a deeper, more complex response to the American scene, one that included simple joy. His western landscapes are genuinely breathtaking, and he depicts the lush charm of Cumberland Island with what seems like un-ironic wonder.

This Land has an elegant foreword by historian Jon Meacham, who describes Spencer’s America as “a transitory place, a place forever in flux,” and there is a sense of sweeping movement to many of the photographs that gently subverts the static subjects. The images seem powerfully real, and at the same time like illusions that could disappear in the next moment. And, of course, the concrete reality they record is in danger of disappearing, a fact Spencer was acutely aware of as he traveled around the country. Over the course of thirteen years, he says, “I saw not only the astonishing beauty of this land but also scars of change ever more blatant and pervasive.” In both his images and his words, he makes a compelling plea for shared reverence toward that beauty and the sustenance it provides for body and soul.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.