The Dark Web

In Move Fast and Break Things, dystopia is now, but it didn’t have to be

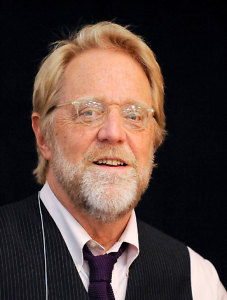

Jonathan Taplin is no technophobe. He founded a video streaming start-up before consumer broadband was widely available, and he is director emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California. So when he throws red flags, it’s not the knee-jerk reaction of an old man yelling at the cloud. Taplin’s new book, Move Fast and Break Things, doesn’t fit neatly onto familiar tech- or business-writing pegs, which is both a feature and, at times, a bug.

Subtitled How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy, the book is a cautionary tale wrapped in a sociopolitical argument, inside a personal journey—which is to say, it jumps around a bit and may fall short of expectations for readers who come to the book with deep knowledge of economics, tech history, American politics, or the slimier corners of the Internet. But as an associative, sometimes almost meditative work of humanist dot-connecting, Move Fast and Break Things is a compelling work with a clear central vision and a cumulative power that is convincing overall.

Subtitled How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy, the book is a cautionary tale wrapped in a sociopolitical argument, inside a personal journey—which is to say, it jumps around a bit and may fall short of expectations for readers who come to the book with deep knowledge of economics, tech history, American politics, or the slimier corners of the Internet. But as an associative, sometimes almost meditative work of humanist dot-connecting, Move Fast and Break Things is a compelling work with a clear central vision and a cumulative power that is convincing overall.

Taplin spent time in the 1960s and ‘70s as a tour manager for Bob Dylan and The Band. He also worked as a film producer for directors such as Martin Scorsese, Wim Wenders, and Gus Van Sant. (His work includes The Last Waltz, which will comprise some of the discussion at his Nashville appearance.) These formative experiences set a kind of artistic and ethical foundation for the book. And while Move Fast and Break Things takes its title from a Mark Zuckerberg quote, the blurb on its cover comes not from a technologist or futurist but from producer and musician T Bone Burnett. It is likely the only book on the rise of Internet culture to devote an entire chapter to the late drummer Levon Helm.

Therein lies the cautionary tale. Helm played with The Band in their ‘60s and ‘70s heyday, and made something in the neighborhood of $100,000 a year from royalties. Then two things happened: Helm was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1999, and Napster launched in 2000, making almost any album available for free over its peer-to-peer network. As Taplin tells it, Helm had no choice but to start hosting concerts in his barn as fundraisers to pay for his medical bills:

Throughout this time, while Levon was barely scraping by, the recordings of The Band continued to be listened to by new generations of musicians, including Mumford & Sons. But because fans listened on pirate sites or YouTube, Levon had no income stream from this amazing catalog. When he died in 2012, his friends held a benefit …. so his wife, Sandy, could hold on to the house in Woodstock. Here is the human cost of the Internet revolution.

If Levon Helm is this story’s tragic hero, one wonders how he ever stood a chance against the league of shadows assembled against him—and, by extension, us. They are: Peter Thiel, who founded PayPal, was the first major investor in Facebook, and has publicly thrown his support behind Donald Trump; Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon; and Google, more or less in its entirety. (Taplin sees a spark of hope that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg is beginning to see the light. Your mileage may vary.)

Move Fast and Break Things is strongest when presenting and connecting its pillar arguments. First, the web began as a decentralized, democratic way of sharing information—it was dreamed up, in part, by acid-dropping free thinkers who also brought us the Whole Earth Catalog. Second, that “original mission,” Taplin writes, was “hijacked by a small group of right-wing radicals to whom the ideas of democracy and decentralization were anathema.” Third, the Big Three tech companies—Amazon, Facebook, and Google—are monopolies that exert undue power that goes unchecked thanks to a lax regulatory atmosphere created and maintained by amoral Ayn Rand acolytes who don’t care about anything but their own power and wealth. Fourth: monopolies with unprecedented surveillance and data collection capabilities are bad for democracy, bad for America, and work against our founding principles.

Move Fast and Break Things is strongest when presenting and connecting its pillar arguments. First, the web began as a decentralized, democratic way of sharing information—it was dreamed up, in part, by acid-dropping free thinkers who also brought us the Whole Earth Catalog. Second, that “original mission,” Taplin writes, was “hijacked by a small group of right-wing radicals to whom the ideas of democracy and decentralization were anathema.” Third, the Big Three tech companies—Amazon, Facebook, and Google—are monopolies that exert undue power that goes unchecked thanks to a lax regulatory atmosphere created and maintained by amoral Ayn Rand acolytes who don’t care about anything but their own power and wealth. Fourth: monopolies with unprecedented surveillance and data collection capabilities are bad for democracy, bad for America, and work against our founding principles.

Those “right-wing radicals” are not some fringe junta; they’re an integral piece of source code for the apps and devices we increasingly depend on. Taplin puts quotes from Ayn Rand (“achievement of your happiness is the only moral purpose of your life”) next to quotes from Peter Thiel (“I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible”), and it is not long before he can draw this line: “Libertarian philosophy … has become the mainstream economic philosophy for both Silicon Valley and the Republican Party, thanks to the Koch brothers.”

Taplin recounts the story of an Amazon warehouse in Pennsylvania where temperatures sometimes reached 110 degrees in the summer. Instead of installing air conditioners, Amazon paid an ambulance company to station paramedics outside during a heat wave. There’s plenty of blame to go around, though, and Taplin doesn’t set his sights only on Republicans. He takes Bill Clinton to task for the Internet Tax Freedom Act, which Jeff Bezos had lobbied for and which cleared the way for Amazon to squeeze out small bookstores by escaping taxes and therefore undercutting on price.

This book’s biggest weakness is the implicit belief that one sort of monopolistic meritocracy, i.e., major record labels, is good, where another sort is bad. Use your search engine of choice—Duck Duck Go, for its part, says it won’t track you—and you’ll find plenty of people who consider major labels no more altruistic, at their core, than tech companies.

But this is a minor quibble. To read Move Fast and Break Things is to be forced to ponder one’s implicit support of technological platforms whose creators are, on matters of markets and deregulation, more closely aligned with the likes of Robert Bork, Paul Ryan, and Grover Norquist than with, say, Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

Certainly, this is not a problem if you already identify with the Randian wing of economic thought. But fascist troll Milo Yionnopoulis’s praise for Peter Thiel when he sued media company Gawker out of business (“Thiel has perhaps done more than any man to liberate social media from the terror of left-wing public shaming”) will remind other readers that there is a lot at stake in Move Fast and Break Things, and a real urgency to do something about it.

Steve Haruch lives in Nashville. His writing has appeared at NPR’s Code Switch, The New York Times, and the Nashville Scene, where is he is a contributing editor.