The Choice Either to Wail or Smile

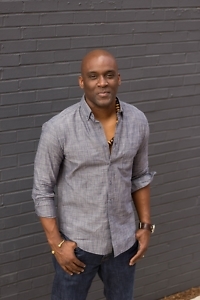

Tim Gautreaux talks with Chapter 16 about his story collection, Signals

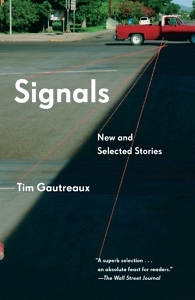

Best known for his novels set in early-twentieth-century Louisiana, Tim Gautreaux is also a master of the contemporary short story. Signals, his latest collection, is newly out in paperback. Composed of twelve new stories and an additional nine from previous collections, Signals serves both as a remarkable addition to a formidable body of work and a sort of career retrospective.

The book is a perfect introduction to Gautreaux’s short fiction, which veers from the historical sweep of his novels to the travails of seemingly smaller, less remarkable lives. “He has the talent and empathy to find the extraordinary in seemingly ordinary lives, rendered in prose that has the precision and memorability of poetry,” Ron Rash has said.

Gautreaux is frequently compared to Flannery O’Connor because of the tangible influence of Catholicism on his themes, and to his former teacher James Dickey for the languid lyricism of his prose. Other comparisons come to mind when reading Signals—Carver and Ford, Cheever and Updike—but these points of reference serve only as signposts leading to a territory that Tim Gautreaux has been crafting with his own distinct style and sensibility for an entire career.

Gautreaux, who recently retired to Chattanooga, answered questions from Chapter 16 via e-mail:

Chapter 16: Because you have written several very popular and acclaimed novels set in the Deep South, you are generally regarded as a “Southern writer,” but the stories in Signals cast a much wider net in terms of settings and characters. To what extent do you feel influenced or constrained by your identity as a Southerner?

Gautreaux: I honestly don’t think about geographical identity. A good story is a good story and the themes I deal with are universal. It’s a delusion to believe that Southerners are more interesting than Midwesterners or Canadians. We all hurt or are overjoyed by the same events.

That said, if an author is familiar with a certain region and its people, he can use that knowledge to abet everything else going on in a narrative. But for a writer who lives in the South to believe that the only thing you can write about is where you were raised puts you in danger, to paraphrase Walker Percy, of being in the business of amusing Yankees.

Chapter 16: These stories seem strongly influenced by Flannery O’Connor, at least in the presence of themes revolving around Catholicism and Catholic theology. How does that influence continue to shape you, and/or how has it evolved?

Chapter 16: These stories seem strongly influenced by Flannery O’Connor, at least in the presence of themes revolving around Catholicism and Catholic theology. How does that influence continue to shape you, and/or how has it evolved?

Gautreaux: The most important part of a boat is the rudder. Without my faith I would have an aimless existence and would be writing novels full of zombies and vampires.

Chapter 16: You are a former student of the late James Dickey, whose work seems to be rising in stature just as the kind of voracious, untamed masculinity he so famously embodied is suffering an enormous public backlash. Is Dickey still a conscious influence for you?

Gautreaux: Dickey was an excellent teacher. What I took away from his classes was the notion that imaginative writing could be made of artfully executed language. All that business about masculinity as it related to shooting a bow and arrow or having sex in a junkyard went over my left shoulder as I dodged it. There’s a lot more to being a man than being “masculine.”

Chapter 16: In its review of Signals, The New York Times quotes your own description of your method: “I try to imagine a normal, average man, with a old boring job, and give him a problem.” Is it really that easy?

Gautreaux: It’s a start, like playing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” on the piano with one finger. But then you have to play “Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.”

Chapter 16: Your stories seem to share O’Connor’s grim wit and dim view of humanity, and yet even in the darkest of them, yours seem imbued with a sense of hope or optimism that can be hard to come by in O’Connor’s. Am I misreading this?

Gautreaux: I take issue with your words “grim” and “dim.” A couple reviewers called my characters “losers.” I don’t see this about my people at all. Such comments must come from readers who have university degrees and were raised in the hothouse attitudes of a wealthy subdivision. The notion that bug exterminators and piano tuners are “losers” reflects the intolerant condescension that is dividing this country.

O’Connor was a master at blending humor, ignorance, and poverty but was short on compassion, or at least the ability to handle her miscreants with a nuanced understanding touch. In my fiction, humor is a topical anesthetic for the reader, keeping him up in the face of some dark doings. O’Connor’s work led me to this notion, but her take on humor was a bit different from mine. As for hope, who the hell wants to read anything with no hope in it? Even a Mad Max movie has hope.

Chapter 16: Many writers no doubt connect with “The Review,” in which a debut novelist hunts down the author of a scathing one-star review posted on Amazon. Do you read your own reviews, and if so, how do they affect you?

Gautreaux: Yes I do. I look for areas in which I might improve. Except for trolls, most people take the time to criticize with the hope that you will get even better.

Chapter 16: Many of the stories in Signals are leavened by your gift for humor, be it a turn of phrase, a descriptive detail, or an unexpected eruption of comic violence. Do you find dismal situations surmountable—or at least endurable—through a comic perspective?

Gautreaux: We all have the choice to either wail or smile.

[This interview originally appeared on February 12, 2018]

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.