Laying the Foundation

Mary Ellen Pethel’s Athens of the New South credits Nashville colleges for the city’s post-war prosperity

Nashville has become famous for its music scene and night life: the waves of bachelorette parties that pack lower Broadway and the boisterous fans who spill out of Predators games seem a world away from the halls of academia, but Mary Ellen Pethel, who holds teaching posts at Belmont University and the Harpeth Hall School, reminds us that Nashville first made its national reputation as a college town. In Athens of the New South, Pethel argues that the foundations of the city’s economy and culture are its institutions of higher education.

“[T]he story of Nashville is linked to the city’s mutually beneficial relationship with local colleges and universities,” Pethel writes. Prior to the Civil War, the University of Nashville was the only accredited liberal-arts college in the area. In the fifty years after the war, the city saw the launch of nine new institutions, all of them “top-tier educational heavyweights in their respective areas,” according to Pethel.

“[T]he story of Nashville is linked to the city’s mutually beneficial relationship with local colleges and universities,” Pethel writes. Prior to the Civil War, the University of Nashville was the only accredited liberal-arts college in the area. In the fifty years after the war, the city saw the launch of nine new institutions, all of them “top-tier educational heavyweights in their respective areas,” according to Pethel.

The explosive growth of Nashville as an academic center was not a matter of chance but the product of careful planning on the part of the city’s farsighted leaders. Nashville “intentionally invested in the power of higher education in order to bolster a particular vision of the city’s future,” she writes. As a local businessman put it in 1914, colleges are an economic and cultural boon: “[We] have figured out that a university that has an average attendance of 1,000 is worth infinitely more to a city than a steel plant or an industry that gives employment to 1,000 men.”

Nashville colleges helped craft the city’s identity during Reconstruction, when the South struggled to modernize without losing its regional distinctiveness. According to Pethel, the transformation of Nashville occurred in two distinct stages: “From 1865 to the Centennial Exposition in 1897 Nashville searched for its place in the postbellum South. From 1897 to 1930 Nashville completed its New South city makeover.”

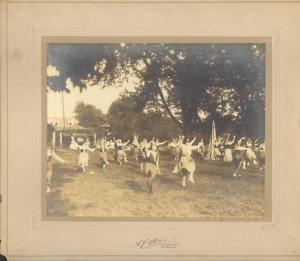

The Centennial Exposition, located on land thereafter known as Centennial Park, became a showcase for the region’s colleges, whose nearby campuses put them on display for visitors from around the world. The Exposition’s success confirmed that Nashville was on the right path, one that distinguished it from other Southern cities: “[H]igher education was part of the very fabric of the city and, in turn, an essential part of the whole cloth of the city’s image, reputation, and appeal.”

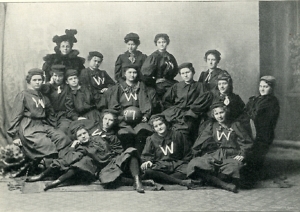

Pethel is particularly interested in the way the expansion of Nashville’s educational institutions affected women and African Americans—groups who, prior to the Civil War, were systematically excluded from higher learning—and the way their inclusion in post-secondary education reflected broad changes in American society. The educational gains were not distributed equally, but Pethel makes it clear that opportunities for women and African Americans in Nashville surpassed what was available in most of the South. The “modern belles” who attended co-ed institutions such as Vanderbilt, which officially endorsed female enrollment in 1895, and the all-girls Ward-Belmont Seminary gradually pushed the boundaries of propriety for Southern women.

Pethel points out that, while graduates of Fisk University and Meharry Medical College “formed the backbone of Nashville’s black elite,” the region’s historically black colleges often reinforced the intractable problems of segregation and inequality. The existence of black colleges in north and northwest Nashville created a positive nexus of business and culture, but it also deepened social divisions. By 1930, she writes, “Nashville neighborhoods were effectively identified according to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic rank.” Despite this drawback, the region’s black colleges enabled the emergence of a “materially prosperous and culturally affluent black community” that later put it in an ideal position among Southern cities to lead the civil-rights movement.

Athens of the New South is packed with illuminating detail and illustrated with dozens of period photos and maps, and readers will be amused by Pethel’s descriptions of the ways colleges around the turn of the century helped transform the social scene for young people. A grave concern for college administrators were the growing number of parties where women and men danced (unchaperoned!) and drank liquor and generally invited the devil to enter their bodies.

In a 1910 chapel talk, Chancellor James Kirkland warned the Vanderbilt community that libertines and addicts threatened to overrun the campus. “The temptations of college life to-day are much greater than ever before,” Kirkland said. “The dangers are greater and the freedom is more complete.” By the 1920s, reformers believed that college students now sought pleasure only in “cheap thrills and vices such as alcohol and sex.” The precipitous popularity of college football generated parallel hand-wringing over tailgate drunkenness and postgame fisticuffs. Plus ça change.

In a 1910 chapel talk, Chancellor James Kirkland warned the Vanderbilt community that libertines and addicts threatened to overrun the campus. “The temptations of college life to-day are much greater than ever before,” Kirkland said. “The dangers are greater and the freedom is more complete.” By the 1920s, reformers believed that college students now sought pleasure only in “cheap thrills and vices such as alcohol and sex.” The precipitous popularity of college football generated parallel hand-wringing over tailgate drunkenness and postgame fisticuffs. Plus ça change.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, as Nashville’s private institutions rose to prominence, the Tennessee legislature increased the number and quality of public schools, as well. The General Education Bill of 1909 “funded school and circulating libraries, established a teacher-certification system and created four normal [teaching] schools.” These educational improvements centered on Nashville colleges, whose graduates moved around the state and country as teachers and professionals. Their success burnished the city’s reputation, helping to create a cultural and economic feedback loop that continues to nourish Nashville over a century later.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.