Rugged Country

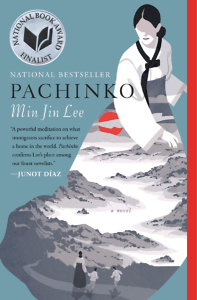

Min Jin Lee discusses identity, diaspora, and resistance in her novel Pachinko

There is a Korean concept known as han, which is widely considered untranslatable. The Los Angeles Times once called it “as amorphous a notion as love or hate: intensely personal, yet carried around collectively, a national torch, a badge of suffering tempered by a sense of resiliency.” Min Jin Lee’s most recent novel, Pachinko, never mentions the word han. But in its beguiling and nuanced way, it is at once a kind of scrolling, epic illustration of the concept and a tender, heartrending rebuke of the notion that any sort of unifying identity, across time and diaspora, can ever be easily described or distilled.

Where other writers might try to dazzle with wordplay, Lee maintains an almost journalistic narration that is deceptively straightforward. Nothing is overstated; everything that happens is important; every detail illuminates. Similarly, there is no structural sleight of hand. Pachinko begins in Korea, before there was a North and a South, around the turn of the twentieth century, and proceeds chronologically for about a hundred years. We are introduced to a single Korean family, whose matriarch, Yangjin, gives birth to a daughter in Korea under Japanese occupation. We follow them across four generations, through war and emigration, destitution and triumph. All the while, they are haunted by the intermittent and sometimes invisible influence of—to say much more would risk spoiling it—a dangerous legacy.

As ethnic Koreans living in Japan, Sunja and her extended family are perpetual foreigners. And while the analogy is far from perfect, echoes of the recalcitrant xenophobia of this country, in this time, chime in the background of Pachinko: immigrants doing the work native Japanese don’t want to do; the humiliation of documents and the specter of deportation; the stubborn stereotypes that attach even to Koreans born in Japan.

But an accounting of social problems does not an effective novel make. Lee knows the cumulative power of story and strikes an indelible balance between historical sweep and the most intimate of human moments. Through the meticulous accrual of gesture and action, we witness the dignity and brutality of work, the hardship of being a woman in a patriarchal world, of being poor and foreign and despised.

All this would seem unbearably bleak were it not for how alive and human the characters are, even as their world seems to collapse on them again and again. At one point, we read the thoughts of a pachinko parlor owner: “He understood why his customers wanted to play something that looked fixed but which also left room for randomness and hope.” The same might be said of this rich and wondrous novel.

Min Jin Lee recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: In the book’s acknowledgements, you mention some real-life incidents that informed Pachinko—two involving Korean-Japanese boys. And yet Sunja is in many ways the anchor of the story. Having done so much research to anchor the novel in history, how did you arrive at the main family narrative?

Min Jin Lee: In my interviews and research, I learned about the primacy of the illiterate, first-generation women, who made extraordinary sacrifices and lived valiantly, and I wanted very much to portray the families that such first-generation women raised.

Chapter 16: Your narrator is omniscient, sometimes at a remove and other times revealing characters’ inner thoughts. The first words of the book are, “History has failed us,” an indictment which seems to include the narrator. Can you talk about that? Did you imagine the narrator as part of the Korean diaspora?

Lee: It’s the only line in the book that has a first-person plural, and it is a hat tip to Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. The first-person narrator appears on page one of Madame Bovary and then leaves, with Flaubert switching to the omniscient narrator. I wanted to share my thesis to my readers about the inequity of history and the defiant strength of those who resist.

Chapter 16: One line that really struck me is, “For people like us, home doesn’t exist.” It was a bit jarring to have it spoken by one of the book’s most despicable characters. Are there any special challenges in writing about unsympathetic characters?

Chapter 16: One line that really struck me is, “For people like us, home doesn’t exist.” It was a bit jarring to have it spoken by one of the book’s most despicable characters. Are there any special challenges in writing about unsympathetic characters?

Lee: I like my unsympathetic characters. Stories cannot exist without conflict, and life doesn’t exist without great friction from unsympathetic people. Consequently, as a storyteller, I need unsympathetic characters, and they are not always villains. They are just that—unsympathetic.

Chapter 16: Yangjin says that it’s a woman’s lot to suffer, and the book provides an overwhelming amount of evidence to support that theory. On some level Phoebe, the American, seems to represent a way out of that cycle because of her strong sense of self-determination. But she also seems the least connected to her Korean heritage. What’s your reaction to that assessment?

Lee: I think women who are fortunate enough to live in democracies and free-market economies that are advanced suffer significantly less than women around the world who are subject to legal, religious, and economic patriarchal systems. Phoebe has the freedom to leave a situation that she does not want, and that is very powerful. That said, women everywhere still have to negotiate their lives differently because of their biology, and that is important today even in advanced democratic economies.

Chapter 16: One character says he understands why his customers like to play pachinko—because it “left room for randomness and hope.” Your recent essay in The New Yorker about the Pyeongchang Olympics suggests you might see some hope for the two Koreas going forward. How are you feeling now that the games are over?

Lee: I remain hopeful, but I think none of us are naive about the interests of many nations regarding the reunification of the two Koreas. That said, we have to be wise and hopeful to have peace, because the alternative is too horrible.

Chapter 16: Some of the characters in Pachinko view America as a kind of utopia, but there are certainly echoes of the debates we are having (again, and always) in the U.S. about immigrants’ lives, legal standing, and vulnerability, though you actually wrote this book before the 2016 election. When you speak to audiences, how do they respond to this increasingly difficult context for immigrants?

Lee: I take the long view on this. The Chinese in America were so unwanted at one point in history that there was federal legislation barring them. The Japanese and Japanese-Americans were sent to concentration camps during World War II although German-Americans were not. Anti-immigrant sentiment has always existed, and it is, to my view, always ugly as well as economically foolish and short-sighted. However, I take great comfort in seeing the organization and the active resistance from many corners of this great country to support and advocate for those who are alien, forgotten, and unfairly despised.

Chapter 16: Over the course of the novel, the questions of what it means to be Korean, or Japanese, become increasingly complex. Did writing this book affect your sense of what constitutes, for lack of a better word, Korean-ness?

Lee: This is a smart question because you answered my goal. I wanted to complicate the sense of what it means to be Korean in a diasporic world. This question must be asked and answered by everyone now in a transnational world where we are linked and connected. Everyone has to ask herself what it means to be Italian, Jewish, Muslim, Straight, Gay, Married, Single, Irish, Indian, et cetera. I think we should be having this discussion because it affects our daily lives, government policies, and our personal and geographic boundaries.

[This article originally appeared on 3/14/2018.]

Steve Haruch‘s writing has appeared at NPR’s Code Switch, The New York Times, and the Nashville Scene. He is the editor of People Only Die of Love in Movies: Film Writing by Jim Ridley, coming in August 2018 from Vanderbilt University Press.