American, No Hyphen

Tayari Jones talks with Chapter 16 about her newest novel, An American Marriage

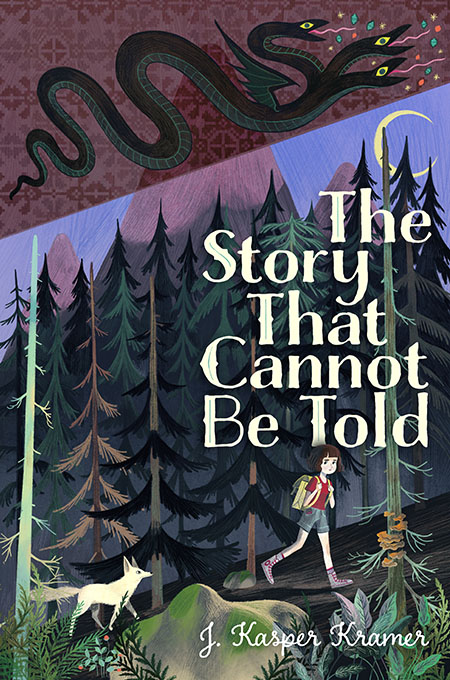

In An American Marriage, Tayari Jones’s fourth novel, an Atlanta couple has been married only a year and a half when the husband is falsely accused of raping a woman in a rural motel. He was sleeping with his wife at the time of the crime, but the alibi is disregarded by his jury. So Roy, an upwardly mobile Morehouse graduate married to an artist from a well-to-do Atlanta family, is suddenly, shockingly a convict. Whether a young marriage can endure such an assault by the justice system is a question Jones explores in this potent and intimate tale, an Oprah’s Book Club selection for 2018.

Jones studied mass incarceration at Harvard but says it was an argument she overheard while shopping at a mall that animated her story. A well-dressed woman was telling a man with scuffed shoes that she knew he wouldn’t have waited for her for seven years. The man’s answer, which Jones uses in her novel: “This wouldn’t have happened to you in the first place.”

Jones, who will appear at the 2018 Southern Festival of Books, answered questions from Chapter 16 by email:

Chapter 16: You were a gifted student who started college at Spelman when you were just sixteen years old. Pearl Cleage, author of What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day, an Oprah’s Book Club selection twenty years ago, was your teacher there. How did she influence you?

Tayari Jones : Pearl Cleage was the first person to take me seriously as a writer and an intellectual. She is the kind of person whose high expectations encouraged me to do better. I didn’t feel pressured; I felt positively inspired.

Chapter 16: Your novels—including Leaving Atlanta, Silver Sparrow, and now An American Marriage—are set in, and often very much about, “the A.” This year, you’ll be leaving Rutgers University-Newark to return to your hometown to teach creative writing at Emory University. What aspects of Atlanta inspire you as a fiction writer?

Jones: I first started writing about Atlanta because I was following the old adage, “Write what you know.” But as I kept writing, I began to see Atlanta as uniquely situated for contemporary fiction about America. The South, particularly the urban South, is a microcosm of all the issues facing the country—race, immigration, sexuality issues—it’s all happening in Atlanta. People in the North think of the South as a sort of shorthand for all that’s wrong with America, but look at Georgia. Look at Stacey Abrams (the current Democratic candidate for governor). The South is the future.

Chapter 16: At the outset of An American Marriage, Roy is sentenced to twelve years in a Louisiana prison for a rape he didn’t commit. It’s a case of his accuser’s word against his own and that of his wife, Celestial, who was with him at the time of the rape. You studied mass incarceration on a Harvard fellowship in 2011-12 and have said that you were outraged by what you learned in your research. How did your academic findings shape this story?

Chapter 16: At the outset of An American Marriage, Roy is sentenced to twelve years in a Louisiana prison for a rape he didn’t commit. It’s a case of his accuser’s word against his own and that of his wife, Celestial, who was with him at the time of the rape. You studied mass incarceration on a Harvard fellowship in 2011-12 and have said that you were outraged by what you learned in your research. How did your academic findings shape this story?

Jones: At first, my academic findings sort of stymied my storytelling. I discovered so many urgent facts that I really wanted to share with the whole world. For example, one in twenty-eight school children have an incarcerated parent. That’s family separation happening every day. I wanted to tell the world what I had learned, but statistics aren’t a story. So I had to do so much reading, and note-taking. But then I had to set it aside and let the characters tell me the story. It was hard to trust fiction to do the emotional work and to trust that the emotional work is just as important as the empirical work.

Chapter 16: Your character Celestial, a sophisticated black artist from Atlanta, suspects that she was too “well spoken” to help her husband in front of a white jury in a country town. “Now is not the time to be articulate,” Roy’s lawyer tells her before she testifies. “Be careful when you leave Atlanta, because you’ll end up in Georgia” is a joke you’ve included in your writing before. How has the urban/rural divide affected you?

Jones: Actually, I look at “well spoken” as a class signifier. All her life, Celestial has been told to be “articulate” in order to be taken seriously. But now she is told to be more casual and colloquial to seem genuine. But as I wrote that section, the trial of George Zimmerman was on the news every day. Trayvon Martin’s girlfriend testified to her experience talking to him as he was being stalked by Zimmerman. The girlfriend wasn’t “well spoken” like Celestial, and she was criticized for that. I was really looking at the challenge of being heard as a black woman.

Chapter 16: You were uncertain about using the title An American Marriage for your novel. (The Harvard website announcing your fellowship seven years ago said the book you were working on would be called Dear History.) What were your misgivings?

Jones: I was concerned about two things. For one, the title An American Marriage seemed generic, not specific enough, and in my experience when “American” is used generically, it implies “white American.” It took me a long time to embrace the title and to understand that what happens to my black characters in Atlanta is American and that I had a right to that label without a hyphen.

Peggy Burch was books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis for ten years, and she also worked as a deputy metro editor and Arts & Entertainment editor for the newspaper. She is a graduate of the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University and holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.