A Park for the People

Brooks Lamb tells the history of Overton Park through the eyes of Memphians

A few mornings every week, I take a sweaty, clambering jog through the Old Forest in Overton Park. On most of those mornings, I wave hello to Mike Cody, who is not only a legend in local politics but also manages to keep running, despite his eighty-something years. Reading Brooks Lamb’s Overton Park: A People’s History, I learned that more than half a century ago, Cody delivered a speech protesting the Vietnam War in the same park. This is just one of many nuggets to appreciate in this affectionate, interview-based history of the crown jewel of Midtown Memphis.

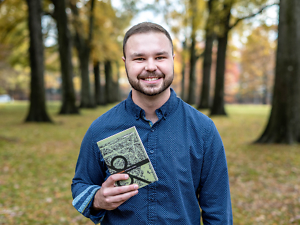

Brooks Lamb is the conservation projects manager for rural lands at The Land Trust for Tennessee. A 2017 graduate of Rhodes College, he wrote Overton Park with assistance from a Bonner Scholarship and a fellowship from the Rhodes Institute for Regional Studies. He answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Brooks Lamb is the conservation projects manager for rural lands at The Land Trust for Tennessee. A 2017 graduate of Rhodes College, he wrote Overton Park with assistance from a Bonner Scholarship and a fellowship from the Rhodes Institute for Regional Studies. He answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: A recurring theme in your book is that Overton Park is for the people. What functions, historically, has the park served?

Brooks Lamb: Like its landscape, the park’s functions have changed dramatically throughout its 100-plus years. What started out as a place intended to, as George Kessler wrote, facilitate “the enjoyment of nature” would later become a haven for recreation and education with the addition of amenities such as the Memphis Zoo, the Overton Park Shell, and the Memphis Academy of Arts. Citizens also established the park as a setting for activism. They used this space to protest the Vietnam War, fight against an interstate that was slated to destroy the park, and help racially integrate public spaces in Memphis through courageous sit-ins. While all of these dramatic and momentous events were taking place, Overton Park remained a park—it was still a place for people to go for a jog or play a round of golf.

The amazing thing about the park is that almost all of its historic functions have persisted into the present. Because of the Old Forest, the park is still a much-loved haven for nature. The park’s multiple amenities and institutions continue to provide world-class educational and recreational opportunities. Citizens still use the park as a place for public discussion and activism. And all of these functions coexist with children exploring the playgrounds, people jogging on trails, and citizens reading or playing catch on the Greensward. In so many different ways, Overton Park has served and continues to serve citizens of and visitors to Memphis.

Chapter 16: Why was Overton Park such a crucial battleground in the Memphis civil rights movement of the 1960s? What did this struggle look like?

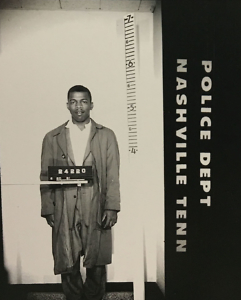

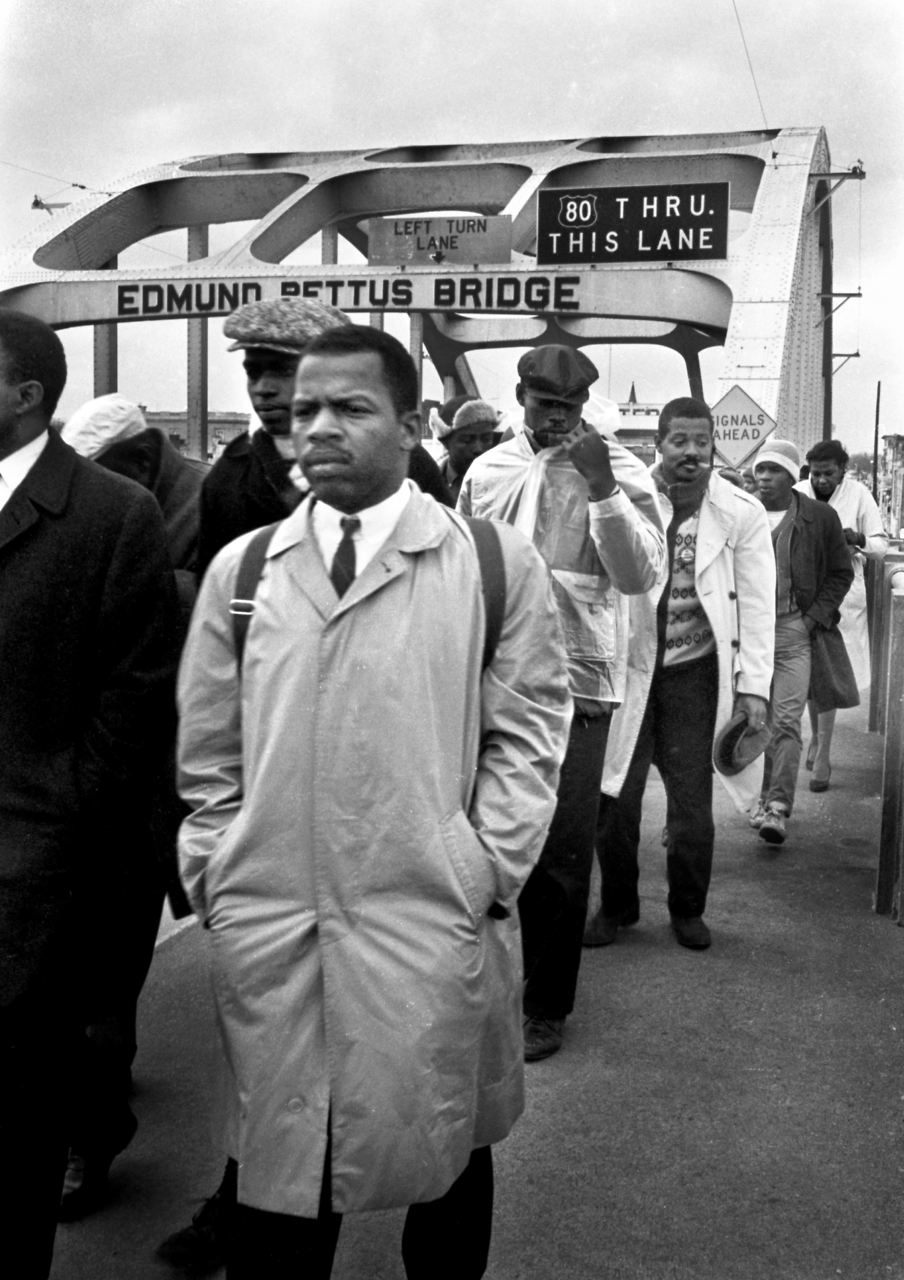

Lamb: Johnnie Turner and Fred Davis—both of whom were integral figures in the Memphis civil rights movement and both of whom were interviewed for this book—explained to me a carefully-crafted strategy for achieving racial integration in Memphis. As opposed to focusing on integrating private businesses like activists in Nashville and Greensboro, Memphis civil rights leaders concentrated on integrating public facilities. They did this because the tax dollars that black Memphians contributed were being used to fund places that granted limited access to black people or barred them from entry entirely.

Because of this strategy, Overton Park became a focus of early integration attempts. The most famous attempt at racial integration within the park happened at the Overton Park Shell, now the Levitt Shell. Johnnie Turner and other black student leaders attended a church service there, and—without giving the entire story away—they were arrested for their efforts. But a few years later, these sit-ins helped yield a monumental legal decision. In Watson v. City of Memphis (1963), the Supreme Court ruled that all public facilities in Memphis must immediately integrate. Partly because of the activism of students such as Turner who fought tirelessly for racial justice, Overton Park and other institutions became open to all Memphians for the first time.

Chapter 16: Overton Park’s history is perhaps most defined by the battle over the route of the I-40 expressway. What did this conflict mean for the fate of the park?

Chapter 16: Overton Park’s history is perhaps most defined by the battle over the route of the I-40 expressway. What did this conflict mean for the fate of the park?

Lamb: Not to be overdramatic, but this conflict was a “life or death” moment for Overton Park. Had highway planners triumphed over Citizens to Preserve Overton Park (CPOP) and routed Interstate 40 through the Old Forest, towering tulip poplars and oaks would have been paved over and replaced by cars and trucks hurtling through midtown. Although plans indicated that the entire park might not have been destroyed, the interstate would have throttled the Old Forest, dimmed Overton Park’s vibrancy, and made this place unwelcoming.

Given that the park is still in existence and is a thriving part of a burgeoning city, one can infer how the story played out: CPOP, a massive underdog, succeeded in keeping the interstate from destroying Overton Park. What we often neglect is how hard—and for how long—they had to fight to protect the park. Although the Supreme Court decision in March 1971 is the pinnacle of this controversy, citizens battled against the state and federal governments in some shape or fashion from the mid-1950s into the 1980s. Understanding the enormity of these efforts makes CPOP’s victory even more admirable and inspiring.

Chapter 16: By the 1980s, the park seemed to be in decline. What happened?

Lamb: The decline of the park in the 1980s can be linked to the expressway battle. For well over a decade, it seemed all but guaranteed that Interstate 40 would run through the park. Charlie Newman, who was CPOP’s attorney in the interstate case, explained to me that he thought the city just ignored the park during this era. Why would they invest in a place that was about to be destroyed? This neglect, coupled with the fact that hundreds of homes and business just outside the park were demolished in anticipation of the interstate, made the park less inviting. When the park’s popularity faltered, some sordid activities—prostitution, drug deals—entered the park, further damaging its allure.

Although the park was certainly dimmer in the 1980s and 1990s, it never died. For that, credit must be given to the folks who continued to care for and use this space during this era. They helped position the park for a renaissance that began in the early 2000s.

Chapter 16: You highlight the influence of “citizen-steward.” How have grassroots organizations shepherded the renaissance of Overton Park?

Lamb: These organizations have been instrumental, and it’s fair to say that the park would look radically different without their persistent efforts. Groups such as Park Friends, Save Our Shell, and the new version of CPOP have played important roles in sustaining and improving Overton Park. The people who make up these groups have demonstrated love for the park and devoted their time and effort to caring for it. Without citizen-stewards—whether they’re part of a formal organization or they just pick up trash on their walks through the forest—Overton Park couldn’t thrive.

Although it’s a different type of organization and is probably not considered grassroots, Overton Park Conservancy has also provided a boon to the park and ensured that its success will continue. Through navigating the park’s everyday challenges and providing essential services to planning community events, installing public art, and fundraising for the park’s future, the staff at the Conservancy has shown a commitment to serving both the people of Memphis and the park itself.

Chapter 16: What are the park’s current challenges? What is its best path forward?

Lamb: Throughout the park’s history, there have been a few constant themes, one of which is change. Whether through its evolving landscape, functions, institutions, or patrons, Overton Park has not remained static. In our present moment, change is entering the park yet again. Recently, the Brooks Museum announced that it will move to the riverfront, and the Memphis College of Art shared that because of financial difficulties, it will soon close. These hallmark institutions will be sorely missed, and their exit leaves many people wondering about the park’s fate.

Those concerned about the park’s future would be well-served by examining its past. Over its 100-plus years of history, Overton Park has endured massive challenges and changes and has been strengthened by these events. This resilience—combined with new, positive changes, including a much-anticipated master plan for the park and the ending of Greensward parking—should grant hope to those who want to see the park live on as an integral part of the city, state, and country.

By spending time in and, hopefully, growing to love Overton Park, citizens can ensure that it will continue to flourish. Just as it has in the past, citizens’ affection for this place will propel it forward.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.