The Shocking Fulfillment of Beauty

Erin McGraw pulls no punches in her new collection of microstories

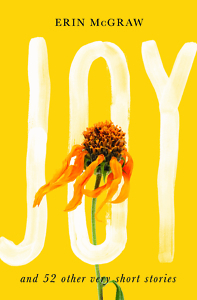

Don’t be fooled by the title or the sunny yellow cover of Erin McGraw’s new story collection, Joy: And 52 Other Very Short Stories. McGraw, who lives in Sewanee, pulls no punches in these snapshots of lives under extreme pressure. Her characters almost always speak in the first person, and what they say is often astonishing. By turns angry, disturbing, darkly funny, poignant, or tragic, each narrator claims the spotlight momentarily to tell a powerful story.

The cast of characters includes murderers and priests, cancer patients and parents with dementia, adulterers and stalkers, prison inmates and the ghosts of loved ones. In the telling first story, “America,” the fussy director of a high-school production of West Side Story explains to his students the point of the play’s conflict: “Inclusion. You’re arguing to prove you belong. There’s nothing more important than that.” McGraw’s own cast of characters would likely agree.

In “The Tenth Student,” a beleaguered piano teacher suffers through clueless students and his own disappointing gifts (“The music I make is bricks tumbling down metal staircases, a fork tine screed over glass”) just for the chance to listen to his star pupil. “The tenth student isn’t here to learn how to play,” he says. “The tenth student comes early, pays up, and when the tenth student plays I brace myself and then still flinch, because the fulfillment of beauty is always shocking.”

“L.A.” depicts a bridal-shop attendant who is puzzled by her aspirational single customers, even as her own marriage begins to fray. “This one’s name is Isabel,” she notes. “Her cake will have musical notes made of lilac fondant. A backup singer, Isabel is looking for a groom who plays the drums, because drummers have great arms and are more trustworthy than guitarists.” At an over-the-top baby shower, the narrator of “Spice” thinks back to the recent past: “Rich and Lindy met after grad school, and during their first date Lindy put on Facebook that she had just met the man she was going to marry. I hoped she was being ironic.”

The straying postal worker of “Pariah” regrets the dissolution of his marriage. “Two nice people can share a house for a long time,” he muses. “They can have nice meals and nice sex. It isn’t a bad life, animated by nice conversations about the people you know. Standing side by side with your spouse, looking out onto your nice life, the view is comfortable. Then one of you looks off to the side, and everything goes to hell.”

The straying postal worker of “Pariah” regrets the dissolution of his marriage. “Two nice people can share a house for a long time,” he muses. “They can have nice meals and nice sex. It isn’t a bad life, animated by nice conversations about the people you know. Standing side by side with your spouse, looking out onto your nice life, the view is comfortable. Then one of you looks off to the side, and everything goes to hell.”

“Soup (3)” is one of a few narratives in which McGraw presents multiple perspectives. In this case, she reveals the thoughts of the husband of a woman dying of cancer, her caretaker friend, and the patient herself, who describes her resignation to the disease: “Pain keeps me company, patiently gnawing. The pain is a lap-sized creature with rich fur and spiky teeth constantly growing in. The only way the animal can stop its own discomfort is to gnaw. One of us has to hurt, and I see no reason why it shouldn’t be me.”

In the intriguing “Edits,” the narrator, who is disabled, explains how her mother’s inspirational memoirs have colored the narrator’s entire life. “In the books I’m adorable” she says. “Even I am charmed by me. There was no telling what I might learn to do. Every moment of the day was devoted to the life I would have. Now, already, that life has happened, and my mother isn’t here to make it sparkle. Without her, I can only see the long difficulty of every day. You, my friend, would be bitter, too.”

Bitterness is not in short supply in Joy, and neither is regret. Hanging over even the lightest of stories is the despair of being misunderstood, left out, or left behind, and these feelings deepen as the pages turn and characters pile up. The short form McGraw has chosen means there is often no resolution for these characters. There’s only a kind of breathless tension that builds throughout the collection. But the amount of emotional weight she is able to pack into such brief encounters leaves no doubt that Joy is a virtuoso performance.

A graduate of Auburn University, Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.