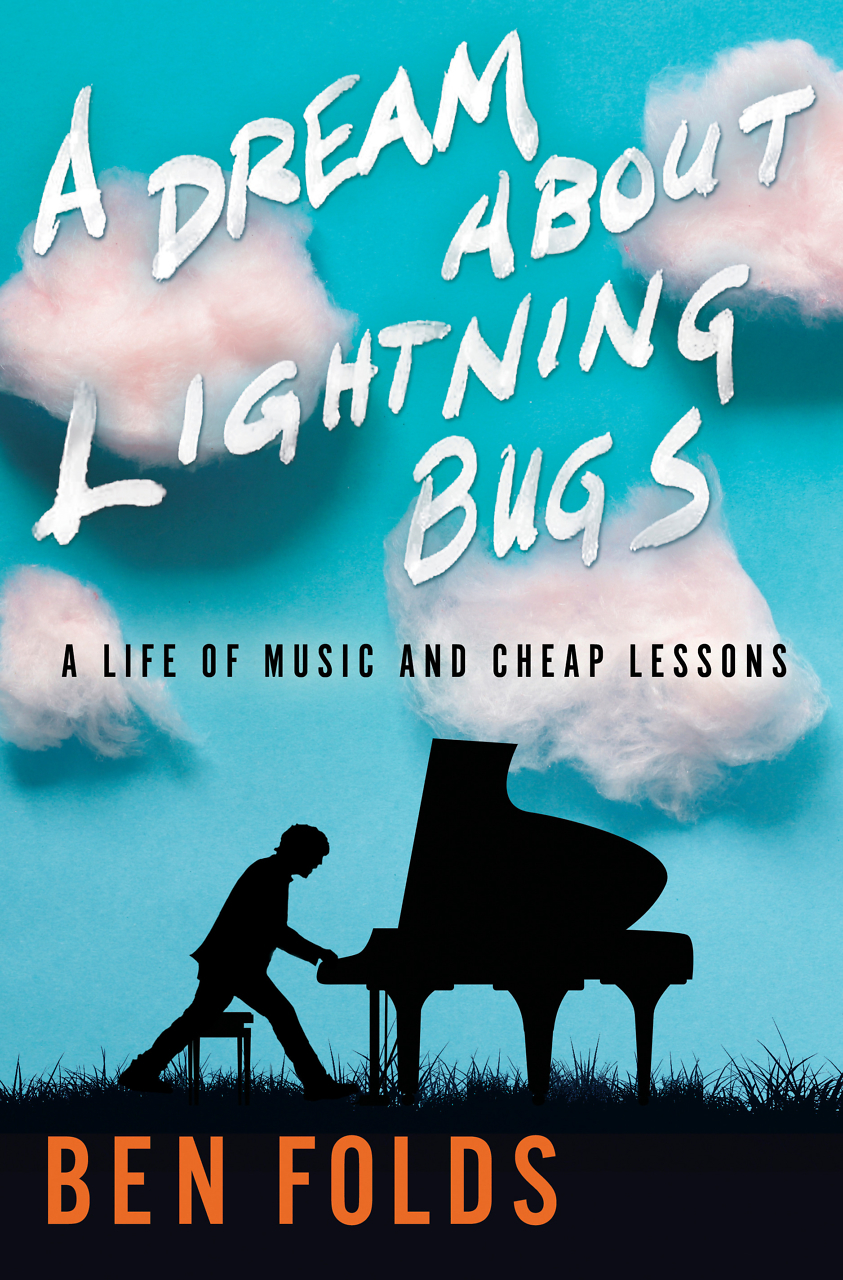

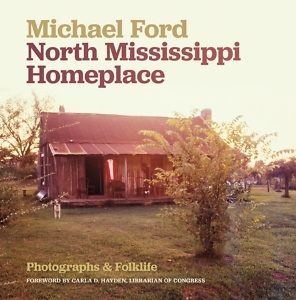

There’s No Place Like Home

Filmmaker Michael Ford’s love for Mississippi takes a new form

In 2016, I won a free drink ticket for doing the Wobble at the Othar Turner Memorial Goat Roast and Picnic in Senatobia, Mississippi. While a significant personal accomplishment, it did not make much of an impression on anyone else at the event. They were busy listening to Como Mamas singing gospel music in the dewy twilight and watching Sharde Thomas, granddaughter of Othar Turner, snaking the Rising Stars Fife & Drum Band through a dancing crowd. It was Mississippi magic—the kind of magic filmmaker Michael Ford conveys in his new book, North Mississippi Homeplace.

In 1972, Michael Ford and his young family traveled from Boston to Mississippi to visit Ford’s in-laws. The trip so changed him that he turned down a coveted teaching job, loaded up the family’s red Volkswagen Vanagon, and headed south. What could Ford have possibly seen that would inspire such a change in plans? Communal hog killings after the first frost. Remote agricultural communities seemingly frozen in time. Animals pulling antiquated farm equipment. Tight-knit communities leaning on each other during lean times, and the quality of light during pearl hour in a Mississippi winter.

Even though Ford was ruined for anything but Mississippi after this first visit, moving from Boston to Oxford in the 1970s was more than a simple change in locations. It was also a change in worlds. Oxford was still a dry town. Mules occasionally wandered down the sidewalks. Most people didn’t lock their cars doors or houses. Jim Crow laws had only recently been abolished.

In Oxford, Ford supplemented his G.I. Bill stipend by working for Marion Randolph Hall, a local blacksmith who repaired agricultural farm equipment. Ford writes that Hall taught him “lessons in hot metal, the proper treatment of people, resolute endurance, handiness, honesty, resourcefulness, ingenuity, and fortitude.” The blacksmith’s position as a community leader lent Ford credibility when he began exploring the state.

Along the way, Ford documented what he saw. The magnetic draw of towns like Chulahoma, Holly Springs, Como, and Harmontown kept Ford in the northern part of the state; he spent the most time in Panola County, north of Sardis. As native Mississippians saw Ford more often, they began to invite him into their lives. He turned this footage into a film, Homeplace, which was released in 1975. Central figures in the film are also featured in this book.

In the film, Hal Waldrip, owner of Waldrip’s General Store in Chulahoma, explains the unique needs of the community by describing the store’s inventory in detail. In the book, Ford describes his friendship with Waldrip and the significance of his store in the community. Master sorghum cooker A.G. Newson and sugar-cane farmer Doc James are also featured in both the film and the book. (A new, nonlinear documentary, closely keyed to the book, can be seen on Vimeo.)

In the film, Hal Waldrip, owner of Waldrip’s General Store in Chulahoma, explains the unique needs of the community by describing the store’s inventory in detail. In the book, Ford describes his friendship with Waldrip and the significance of his store in the community. Master sorghum cooker A.G. Newson and sugar-cane farmer Doc James are also featured in both the film and the book. (A new, nonlinear documentary, closely keyed to the book, can be seen on Vimeo.)

Ford lived in Mississippi from 1971 to 1975 before leaving to pursue a career in filmmaking. The raw Mississippi footage sat in his closet for thirty-seven years. Then, in 2009, at the behest of his daughter, Ford began to process the film and type the transcriptions—some “725 pages of logs and transcripts, 90 audio recordings, 670 photos, 63 film elements.” Thanks to Todd Harvey at the American Folklife Center, these remnants of Mississippi’s past are now housed at the Library of Congress. Photos from this collection make up the first half of this book.

The book’s second half chronicles additional fieldwork that Ford began in 2013. All that archival work had put his old haunts in mind, and he returned to Mississippi with a small crew. People, it turns out, had been waiting for him. Blacksmith Andy Waller picked up where Ford’s mentor left off—in fact, he had been holding tools for Ford that Hall had willed to him forty years earlier. The children Ford had photographed in the ‘70s were grown and wanted to talk.

Some of the towns Ford revisits are sagging, and some are changed but thriving. “When I returned to Mississippi, I thought that I was seeking echoes of old times,” he writes. “Instead, I have discovered myself picking up not where I left off but further on down the line. … I find a continuing love and sense of participation in the North Mississippi hill country. It seems this, in some ways, is still my homeplace.”

Sarah Carter is a high-school English teacher in Lebanon, Tennessee. She holds an M.F.A. in creative writing from the Sewanee School of Letters.