Beyond the Crossroads Myth

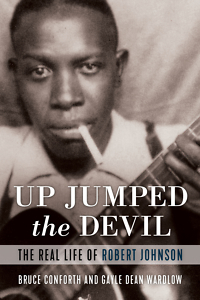

In Up Jumped the Devil, Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow upend popular fantasies about Robert Johnson

Robert Johnson died on August 16, 1938, at the age of twenty-seven. The guitarist, singer, and composer/adaptor of stunning blues lyrics had been handed a drink laced with mothballs, courtesy of the last in a chain of husbands peeved that he was sexually involved with their wives. Revered blues scholars Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow tell this story—and separate the truths from the myths in popular accounts of the musician’s life—in an important and revealing new biography, Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson.

Johnson made twenty records, though only Terraplane Blues and Dust My Broom sold reasonably well. He brought riff-based boogying guitar to music in a way that pre-figured where more urbanized and electrified blues would head a generation later. But in his own time, few recognized his innovations, or even his name.

When a revival of pre-war blues—and Johnson’s music in particular—arrived twenty to thirty years later, the interest was fostered first by record collectors’ research and then by album reissues and a spate of far-from-accurate articles, books, and liner notes. Together they all worked to obscure the man, his life, and the meanings of his songs. All that was left was a mythical figure who wrote poetry like Keats and died howling at the moon on all fours. The story that Johnson “sold his soul to the devil,” often the only story many people “know” about him, was based on often-misquoted remarks by contemporaries such as Son House, as well as by an over-emphasis on some of his lyrics and a tendency to conflate them with his life.

These stories both romanticized and demeaned Johnson, as primitivizing in their way as blackface minstrelsy. Otherwise sober metropolitan newspapers not known for their theological positions, let alone for hoodoo, have felt compelled to headline any mention of Robert Johnson with references to his now famous—if utterly unsupported—stop at the crossroads to sublet his soul to that tricky old devil. It’s as if the man were murdered all over again when his music was revived.

After decades of careful preparation and diligent research, Conforth and Wardlow are forced to admit, “we discovered that what we, and everyone else, believed or thought about Robert Johnson was wrong in some respects.” Accessible and involving, their book fills in almost week-by-week details in the life and rich musical experiences of the man.

They have built that story on the most credible and carefully considered remembrances of people who knew Johnson, serious documentation (Wardlow was the researcher who’d first discovered Johnson’s detailed death certificate), and unique access to a trove of previously obscure research that’s now legendary in blues scholarship in its own right: the unpublished work of the late Mack McCormick, who uncovered Johnson’s complicated family background (and multiple names) and found the two genuine photos of the man ever published.

Up Jumped the Devil spent as much time growing up in Memphis as in the Mississippi Delta. He was pressed by family to remain a sharecropper yet had music lessons when he was young. His education continued under the top Delta blues musicians he apprenticed with. Unlike many down-home musicians of his time, Johnson could read and write—and was good enough as a singer, guitar ace, and harmonica player to take on professional gigs as a young teenager. He would become versatile enough to play Italian or Jewish weddings and was likely to play a pop tune or Jimmie Rodgers song while busking on streets.

Up Jumped the Devil spent as much time growing up in Memphis as in the Mississippi Delta. He was pressed by family to remain a sharecropper yet had music lessons when he was young. His education continued under the top Delta blues musicians he apprenticed with. Unlike many down-home musicians of his time, Johnson could read and write—and was good enough as a singer, guitar ace, and harmonica player to take on professional gigs as a young teenager. He would become versatile enough to play Italian or Jewish weddings and was likely to play a pop tune or Jimmie Rodgers song while busking on streets.

It is striking how much Johnson’s behavior—and the guilt he conveyed in some of his darker songs—predicts the lives of rock and rollers years later: the substance abuse, the endless succession of women attracted by his apparent neediness and vulnerability. He was on the road when his first wife and their child died in childbirth, and his in-laws called it the price he paid for playing “the devil’s music.” You don’t have to give in to dark supernatural forces to be made to feel like you have.

Life details never “explain” musical genius. It is, after all, the power of Johnson’s music that has caused so many people to be obsessed with his story. Conforth and Wardlow offer the clearest portrait yet of the person who held that power.

Barry Mazor’s book Meeting Jimmie Rodgers was published by Oxford University Press in 2009. Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music was published by Chicago Review Press in 2015. Mazor hosts the weekly streaming show “Roots Now” on Nashville’s AcmeRadioLive and reviews country and roots music for The Wall Street Journal.