Never at Home

The characters in Michael Croley’s debut collection struggle to find their place

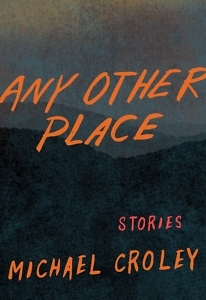

The stories in Michael Croley’s debut collection, Any Other Place, are set in an unlikely mix of locales, including Memphis; Washington, D.C.; Korea; and rural Kentucky. What they share is a powerful theme of exile. Croley’s characters, no matter where they find themselves, seem unable feel at home, and they struggle to understand where — and how—they should be in the world.

Many of his protagonists are bewildered young men, but there are other voices here, as well: an aging widow, an unhappy young mother, an immigrant bride, a new father in wartime. Though some of the events they confront are quite dramatic, these people are quiet and often stoic. They’re the kind of folks who feel deeply but speak with caution. And they’re decent. Their choices may not be altogether good, but their intentions almost invariably are.

Many of his protagonists are bewildered young men, but there are other voices here, as well: an aging widow, an unhappy young mother, an immigrant bride, a new father in wartime. Though some of the events they confront are quite dramatic, these people are quiet and often stoic. They’re the kind of folks who feel deeply but speak with caution. And they’re decent. Their choices may not be altogether good, but their intentions almost invariably are.

Take, for example, the widow at the center of “Solid Ground.” Mrs. Anderson (we never learn her first name) witnesses the freakish accidental death of a young woman on the street outside her home. She tells her story with calm detachment, even with humor. She describes a television reporter’s hair as “stiff enough it could have stopped a brick,” and she can’t get over the feeling that a young police officer is just a little boy playing dress up. At the same time, the horror of the accident brings forth all her unspoken sorrows. She feels an almost motherly kinship with the victim and is drawn to the site of her death:

The asphalt still held the day’s heat, and I ran my hands along the road’s broken edge and felt the soft crumbling of it at my fingertips. The sky was full of stars, and I turned off the flashlight so that I was in the dark. I pictured that young woman once more.

Mrs. Anderson lives in the fictional small town of Fordyce in Eastern Kentucky, which is the setting of several stories in Any Other Place. In “Washed Away,” it’s the new, uncomfortable home of a young Korean woman who has married one of Fordyce’s native sons. In “Smolders” a Fordyce teenager comes to understand that leaving his little hometown for bigger things will mean surrendering some dreams, as well.

Mrs. Anderson lives in the fictional small town of Fordyce in Eastern Kentucky, which is the setting of several stories in Any Other Place. In “Washed Away,” it’s the new, uncomfortable home of a young Korean woman who has married one of Fordyce’s native sons. In “Smolders” a Fordyce teenager comes to understand that leaving his little hometown for bigger things will mean surrendering some dreams, as well.

That teenager, Wren Asher, is a young man living in Washington, D.C., in “Slope,” which focuses on a troubled love affair conducted mostly through trans-Atlantic phone calls. Wren’s lover is an American woman living in Paris with an Algerian partner. In the aftermath of the relationship, Wren returns to Fordyce, taking consolation in the company of his mother, who seems to be the long-ago Korean bride of “Washed Away.” The major themes of Any Other Place converge in “Slope”: displacement, an ambivalent longing for home, and confusion about how to move through the world.

Identity, of course, is also at the core of “Slope.” The title refers to the racist slur, as well as to the mountains surrounding Fordyce and the slippery slope of romantic self-delusion. Wren flies into a rage when an opponent in a pickup basketball game talks about his “samurai chop,” calling forth memories of all the torment he endured as a mixed-race kid in Kentucky. But his Appalachian heritage costs him some pain, too. His lover, who grew up near Boston, says she feels culturally closer to her Algerian partner than to him. People in New York and D.C. “sometimes ask him to repeat what he says, as if he’s a form of entertainment and his speech has the quaint air of someone who is simple.”

Croley, who holds an M.F.A. in creative writing from the University of Memphis, is himself the child of a Korean mother and a white Appalachian father. He grew up in Corbin, Kentucky, and in a recent essay for The Paris Review he describes “Slope” as “the most autobiographical story I’ve ever written.” He writes about home and cultural kinship with a sharp personal understanding of just how complicated those things can be.

Yet nothing in Any Other Place reads like half-disguised memoir, and there’s certainly no hint of deliberate social commentary. This is beautifully wrought fiction, a distillation of experience, observation, and empathy that renders something haunting and rich on the page. Croley’s characters wrestle in their quiet way with the deepest human questions, and these stories linger in the heart.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Still, Hippocampus, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She is the editor of Chapter 16.