Older Ways of Doing Things

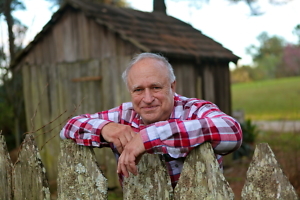

John Coykendall recounts a life’s work safeguarding rare heritage crops and traditional farming methods

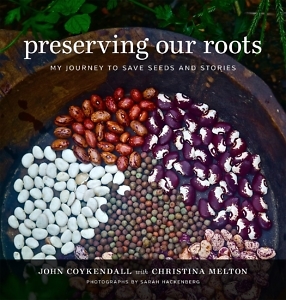

In the introduction to Preserving Our Roots: My Journey to Save Seeds and Stories, John Coykendall recalls how even as a boy he was drawn to elderly farmers, whose life wisdom he craved. “When an old person passes away, it’s like burning down a library,” he writes. He wanted to rebuild those libraries by documenting that older generation’s memories of traditional rural life, “before these old-timers died away.”

Now an old-timer himself, Coykendall has logged thousands of hours on front porches and in garden plots collecting the knowledge of his elders, many of them farmers in his native Appalachia and other parts of the rural South. This book is both a paean to them and an artifact of a bygone way of life that modern city dwellers too often idealize. As one old fellow from Louisiana quipped to Coykendall, “Farm to table? When we were growing up, it was ‘farm to table’ or starve!”

If you’re a lover of Southern foodways, you may know John Coykendall as master gardener at Blackberry Farm, a storied resort in the Great Smoky Mountains and a destination for food and wine connoisseurs. But Coykendall’s vocations range more widely. Born in Knoxville, he learned to garden on a farm owned by his grandfather, a U.S. congressman. He later enrolled in schools of fine arts in Florida and Boston, a study in part fueled by a chance find he made as a teen: At a disused train station, he ran across a William Henry Maule Seed Catalogue from 1913. Paging through archaic botanical drawings of produce varietals he’d never heard of sparked a fascination with art and oldfangled agricultural methods, passions he’s united in his life’s work.

Preserving Our Roots is a sort of travelogue of that life’s work, but the journey is, in part, back in time — and deep into generational memory. The idea came in the early 1970s, when a fellow art student invited Coykendall to visit her family farm in Washington Parish, Louisiana. He fell in love with everything there, from the morning mists to the fierce hospitality that met him. Most years, he returns for a visit, armed with pencil, notebook, and gentle curiosity.

Over the decades he’s filled scores of notebooks with observations, quotations, and drawings, some of which are reproduced in Preserving Our Roots: A pencil sketch of corn and cotton fields is overlaid with a quote from his friend Homer Graves, whose vernacular Coykendall records verbatim: “…them fields wus yor Livin, you did’n have no other way ah makin it …” Another sketch depicts a field sown with “The Unknown Pea,” a species locals told him was ubiquitous in Washington Parish a hundred years ago but had since disappeared. “I ain’t here’d tell of em in years now,” he journals, quoting a woman he met at the annual Washington Parish Fair.

John Coykendall aimed to find that mystery pea. And 10 years later, he did. He’s a man who knows his ladypeas from his purple hulls, a minor distinction that barely scratches the surface of his exhaustive knowledge of the heritage beans and peas of the American South he’s collected during his travels. Anytime he heard of a bygone legume he didn’t have in his collection, he’d hunt one down and ask an old-timer how to cultivate it. Then he’d preserve them in his freezer back home, plant a few, and carry the seeds back to some local farmer who promised to sow them anew. He’s also safeguarded rare seed varieties of okra, squash, tomatoes, and other vegetables native to the South.

Preserving Our Roots, written with documentary filmmaker Christina Melton, chronicles Coykendall’s mission to preserve the old stories, farming methods, recipes, and heritage seeds from the Louisiana community he came to love — cultural treasures he fears would be otherwise lost. The book is a love letter to older ways of doing things and to the older people who passed that knowledge to him. Readers will enjoy trying their hand at farmhouse staple recipes that Coykendall has dutifully written down, such as “Ruthie Mae Graves’s Turnips and Greens with Cornbread Dumplings” and “Maw Lang’s English Pea and Tomato Salad.”

Preserving Our Roots, written with documentary filmmaker Christina Melton, chronicles Coykendall’s mission to preserve the old stories, farming methods, recipes, and heritage seeds from the Louisiana community he came to love — cultural treasures he fears would be otherwise lost. The book is a love letter to older ways of doing things and to the older people who passed that knowledge to him. Readers will enjoy trying their hand at farmhouse staple recipes that Coykendall has dutifully written down, such as “Ruthie Mae Graves’s Turnips and Greens with Cornbread Dumplings” and “Maw Lang’s English Pea and Tomato Salad.”

Although the sheer enjoyment of all those porch-sitting hours comes through vividly in these pages, Coykendall hopes to impart a more urgent and practical message: Preserving a rich variety of edible crops and the knowledge of how to cultivate them is essential to human survival. It’s something previous generations knew by instinct: Farm-to-table isn’t a luxury; it’s a life. As a Mississippi farmer once told Coykendall as he bequeathed him with an heirloom butter bean variety called “Snow on the Mountain”: “You keep this seed and you grow it. You take care of this bean throughout the rest of your life and it will take care of you. You will never go hungry.”

Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators.